The Distal Tarsal Tunnel: First Branch of the Lateral Plantar Nerve Release

Robert M. Goecker

In most patients, plantar heel pain has been attributed to plantar fasciitis or heel spur syndrome. However, in select individuals, another distinct entity can reproduce similar pain and symptoms. Several authors have described a neurogenic source of heel pain created by an entrapment of the first branch of the lateral plantar nerve (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15 and 16).

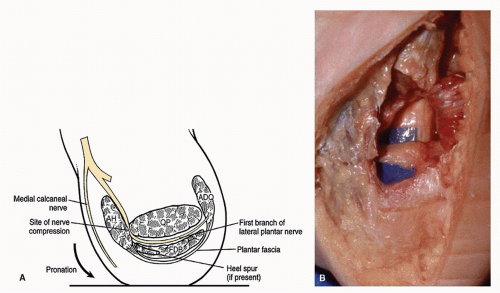

The first branch of the lateral plantar nerve is a mixed nerve with both motor and sensory fibers. Muscles supplied by this nerve include the abductor digiti minimi, flexor digitorum brevis, and quadratus plantae. Sensory fibers supply the calcaneal periosteum, long plantar ligament, and the skin at the plantar lateral aspect of the foot. This branch originates from the lateral plantar nerve proximal to the abductor hallucis and then dives through the fascia at the superior margin of the abductor. The nerve courses distally between the abductor hallucis muscle and the medial edge of the quadratus plantae until it reaches the inferior margin of the abductor fascia. There it turns laterally between the flexor digitorum brevis and the quadratus plantae (1). The nerve at this point lies adjacent to the calcaneus approximately 0.5 cm distal to the medial tubercle of the calcaneus (2,3).

Poor results following traditional heel spur surgery may be due to damage and subsequent entrapment of the first branch of the lateral plantar nerve. Poor results after fasciotomy procedures may be due to an inadequate release of a primary neurogenic source of heel pain. Obviously the nerve is not adequately addressed or released through the traditional open heel spur surgical approach or newer fasciotomy techniques. This nerve branch should not be confused with the medial calcaneal nerve, a purely sensory nerve that lies in the superficial fascia of the heel (4,5).

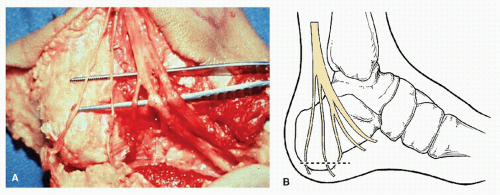

In 1963 Tanz (6) proposed that the first branch of the lateral plantar nerve may be an overlooked source of plantar heel pain and he demonstrated the nerve’s anatomy from cadaveric dissection (Fig. 40.1). However, in 1981, Przylucki and Jones (3) correlated actual patient symptoms with this structure. Their surgical treatment for this condition consisted of excision of the nerve. Subsequently, other authors have reported successful treatment of this type of chronic heel pain with external neurolysis versus nerve excision (1,4,5,7,8,10,11,12,13,14 and 15).

Baxter et al in 1984 described two possible sites of entrapment. The first can occur at the sharp fascial edge of the abductor hallucis muscle when the nerve changes course and turns laterally. Another possible site is at the medial ridge of the calcaneus where the nerve passes beneath the tuberosity and origin of the flexor digitorum brevis and the plantar fascia (7). Therefore, nerve impingement may be caused by an increase in mass within the flexor digitorum brevis such as a calcaneal spur (11). Rondhuis and Huson (16) concluded that the exact site of the entrapment occurs where the nerve passes between the taut deep fascia of the abductor hallucis muscle and the medial caudal margin of the medial head of the quadratus plantae muscle (Fig. 40.2).

ETIOLOGY AND DIAGNOSIS

Entrapment of the first branch of the lateral plantar nerve is well recognized but can be diagnostically elusive (9). Patients with heel pain secondary to nerve entrapment may present with symptoms that are slightly different than individuals suffering from plantar fasciitis. In the former condition, the pain is usually not as great in the morning or during poststatic intervals, but seems to be more accentuated after activity (15).

Several factors may contribute to the development of entrapment of the first branch of the lateral plantar nerve. Soft tissue masses or even varicosities may contribute to the compression neuropathy. Pronation (valgus deformity) of the rearfoot may contribute to the neuropathy by increasing tensile load on the tibial nerve and by decreasing the tarsal tunnel compartment volume (17,18). Przylucki and Jones noted that compression of the first branch of the lateral plantar nerve may occur by physiologic motion secondary to pronatory forces. As the foot is pronating, the fascial structures increase in tension, resulting in compression of the nerve (3). This suggests that the nerve compression may not only be static (constant) but also dynamic and can worsen with pathologic gait patterns. Investigational cadaveric study data prove that the pronation of a pes valgo planus deformity (i.e., valgus hindfoot and abducted forefoot) is a cause of tarsal tunnel syndrome due to increased tibial nerve tension. These cadaveric studies have shown increased tibial nerve tension in an unstable compared with a stable foot. There is an increase in the tibial nerve tension in a foot positioned in eversion, dorsiflexion, and combined dorsiflexion-eversion as well as with increased internal rotation (17,18). Finally, muscle hypertrophy or spurring have been cited as potential instigating factors that may irritate the nerve as it passes through the fascia of the abductor hallucis (11,15).

However, in some patients a history more similar to the symptoms associated with plantar fasciitis may be described. Chronic inflammation of the plantar fascia may coexist and possibly predispose to entrapment of the first branch of the lateral plantar nerve (4,5). Therefore, the patient may initially have some component of plantar medial heel pain as well. In these latter cases, the plantar fascial symptoms will tend to respond to the conservative modalities, but the symptoms related to the nerve entrapment may tend to persist. In some instances, the patient may complain of a radiating pain toward the lateral heel following the normal anatomic course of the nerve. There may be associated motor weakness of the abductor digiti minimi visualized by the patient’s inability to abduct their fifth

toe (Fig. 40.3). Abduction of the fifth toe may be a difficult task for many people to perform, but a difference may be observed between the symptomatic and asymptomatic sides in some individuals with this entrapment.

toe (Fig. 40.3). Abduction of the fifth toe may be a difficult task for many people to perform, but a difference may be observed between the symptomatic and asymptomatic sides in some individuals with this entrapment.

Regardless of the history, the diagnosis of entrapment of the first branch of the lateral plantar nerve may be distinguished during the clinical examination. The exact source of the patient symptoms may be derived by close palpation of the plantar heel. Clinically, the pathognomonic sign of this entity is greater pain with compression over the medial aspect of the heel rather than plantarly (Fig. 40.4). Hendrix et al (8) labeled this test as the nerve compression test. Palpation in this region pinches the nerve between the deep fascia of the abductor hallucis and medial caudal margin of the quadratus plantae resulting in pain and possible paraesthesias (1). Hendrix et al (8) have also found that plantarflexion and inversion of the foot (Phalen maneuver) may

be helpful in diagnosing entrapment of the terminal branches of the tarsal tunnel including the first branch of the lateral plantar nerves. This movement reduces the width of the porta pedis and causes the superior margin of the abductor hallucis to compress the nerve reproducing nerve impingement signs and symptoms. The nerve is also felt to be compressed at the exit site of the fascia between the abductor and flexor brevis (4,5).

be helpful in diagnosing entrapment of the terminal branches of the tarsal tunnel including the first branch of the lateral plantar nerves. This movement reduces the width of the porta pedis and causes the superior margin of the abductor hallucis to compress the nerve reproducing nerve impingement signs and symptoms. The nerve is also felt to be compressed at the exit site of the fascia between the abductor and flexor brevis (4,5).

Figure 40.3 The classical point of maximum tenderness in patients with entrapment of the first branch of the lateral plantar nerve. |

The windlass test (extension of the metatarsophalangeal joints) and the dorsiflexion-eversion test (dorsiflexion and eversion of the ankle while extending the toes) have also been described in an attempt to differentiate tarsal tunnel-like symptoms from plantar fascial irritation. Both tests mechanically challenge various structures associated with plantar heel pain by increasing stress on them, but may not differentiate the etiology of plantar heel pain since cadaver studies prove that there is an increased strain on the distal tarsal tunnel nerve branches and the plantar fascia with both maneuvers. Therefore these tests may help initiate a possible diagnosis, but really cannot exclude or differentiate neuritic versus orthopaedically mediated heel pain (19).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree