The practice of medicine in the United States, as in most nations, is profoundly influenced by government rules, regulations, legislation, and enforcement activity. Governments set standards of professional training, define the scope of practice, authorize individuals to practice, monitor practice performance, and enforce compliance with their standards.

Government also strongly influences the activities of health care providers through certificate of need controls, licensure, and public health requirements. Facilities are subject to many operating rules and requirements, are regularly reviewed, and face many obligations as to how they operate and are reimbursed for the services they provide.

The federal government is the single largest payer for inpatient rehabilitation services (through the Medicare program) and hence has a large impact on all providers and facilities in this segment of the health care industry. Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) beneficiaries account for approximately 70% of inpatient rehabilitation facility (IRF) cases (

1), and Medicare spending for IRF services is projected to be $5.8 billion annually in 2008 and 2009 (

2). Medicare actuaries projected $22.8 billion in spending in 2008 at skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) (

3). As a result, the regulations Medicare imposes on providers generally influence practice for all patients, regardless of payer, and become universal standards of compliance.

State governments (in partnership with the federal government) are also very important purchasers of rehabilitation care and services through the Medicaid program. Another dual program of importance, the provision of vocational rehabilitation services, is federally administered by the Rehabilitation Services Administration (RSA) and in each state by its Vocational Rehabilitation Agency.

In addition, government has a central role in assuring protection of patient rights, safety, confidentiality, and nondiscriminatory treatment. The legal system addresses quality of care, access to care, and equity.

Compliance with federal regulations is monitored by the Office of the Inspector General of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the Program Integrity Group of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). State Departments of Health typically provide surveillance for compliance with state laws and the Medicaid program.

In this chapter, we describe the various key legal and regulatory features that control and influence the field of physical medicine and rehabilitation (PM&R).

MEANS OF GOVERNMENTAL INFLUENCE OVER PM&R

As with any regulated field, government influences PM&R through the activities of both the legislative and executive branches. The legislative branch has the sole authority to authorize programs and to appropriate funds. The executive departments and agencies are charged with implementing legislation pursuant to statutory authority, including through agency rulemaking and the enforcement of specific regulatory agendas (

4). The statutory basis for a regulation “can vary greatly in terms of its specificity, from very broad grants of authority that state only the general intent of the legislation and leave agencies with a great deal of discretion to very specific requirements delineating exactly what regulatory agencies should do and how they should take action” (

5). The executive branch may also propose legislation for the legislative branch to consider.

Because the federal government is the single largest payer for rehabilitation services through the Medicare program, the statutes and regulations that set forth Medicare eligibility and reimbursement policies are of primary importance to the practice of PM&R. The following section provides examples from the Medicare reimbursement system to illustrate the means of governmental influence over PM&R.

MEDICARE STATUTES AND THE RULEMAKING PROCESS

The Balanced Budget Act of 1997 (BBA) (PL No. 105-133) authorized a number of major structural reforms to the Medicare program, including the transition to prospective payment systems (PPSs) for Inpatient Rehabilitation Facilities (IRFs), SNFs, and Home Health (HH) Care (

6). Shortly after enactment of the BBA, the Medicare, Medicaid, and State Children’s Health Insurance Program

(SCHIP) Balanced Budget Refinement Act of 1999 (BBRA) (PL 106-113) and the Medicare, Medicaid, and SCHIP Benefits Improvement and Protection Act of 2000 (BIPA) (PL 106-554) authorized payment for long-term care hospitals (LTCH) based on prospectively set rates. Prior to this transition, PM&R providers were reimbursed retrospectively on a “reasonable cost basis” (

7).

These statutes set forth the parameters for each PPS but direct the Secretary of the Department of HHS to implement these payment systems through the rulemaking process. The inpatient rehabilitation facility prospective payment system (IRF PPS), for example, requires providers to be paid predetermined per-discharge rates for “classes of patient discharges… by functional-related groups (each referred to as a “case mix group”), based on impairment, age, comorbidities, and functional capability of the patient and such other factors as the Secretary deems appropriate” (

8). The statute also provides for adjustments for area wage variations; individual facility variations; individual patient outliers; lengths of stay; and the annual market basket inflationary update (

9). In each case, the statute provides the Secretary with discretionary authority to establish the actual classification system for patients; the weighting factors for expected costliness; the payment rates; the outlier and special payment policies; the area wage adjustments; and the annual update (

10). Implementation in these areas involves important methodological considerations and significant determinations as to policy. Express policy objectives set forth in the IRF PPS include providing proper “incentives to furnish services as efficiently as possible without diminishing the quality of the care or limiting access to care” and creating “a payment system that is fair and equitable to facilities, beneficiaries, and the Medicare program” (

11).

For each PPS, the Secretary also issues annually a Proposed and Final Rule to implement, refine, and update the reimbursement system for the upcoming fiscal year (FY) in question. The government publishes a notice of each Proposed Rule in the

Federal Register and solicits stakeholder comments to which it then responds in the Final Rule (

12). The FY 2009 Final Rule for the skilled nursing facility prospective payment system (SNF PPS), for example, provides for a 3.4% market basket update to the payment rates used under the SNF PPS and makes certain changes to the case-mix indexes (

13).

The annual rulemaking process can lead to significant structural changes in the payment system. As added by the BBA, Section 1886(j) of the Social Security Act confers broad statutory authority upon the Secretary to propose refinements to the IRF PPS; parallel provisions exist with respect to the other PPS. Under this authority, for example, the FY 2006 IRF PPS Final Rule made a number of substantial refinements to the IRF PPS case-mix classification system (the case-mix groups and the corresponding relative weights) and the caselevel and facility-level adjustments (

14). Further refinements were made in FY 2007 and FY 2008 “to ensure that IRF PPS payments continue to reflect as accurately as possible the costs of care” (

15).

STATUTORY AND REGULATORY DEVELOPMENTS

Despite the basic relationship between the legislative and the rulemaking processes, policy development is almost never a linear process. In the PM&R context, legislation is often a means to alter, suspend, or otherwise supersede regulatory determinations. Legislation is also often a means to temporarily “fix” or “patch” previous laws, or to seek lasting changes in the payment systems. New statutory provisions, moreover, can establish additional regulatory requirements, which themselves must be implemented.

The list of enactments that have significantly impacted the Medicare program, and PM&R in particular, since the passage of the BBA in 1997, include the Medicare, Medicaid, and SCHIP BBRA of 1999 (PL 106-113); Medicare, Medicaid, and SCHIP BIPA of 2001 (PL 106-554); Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003 (PL 108-173); Deficit Reduction Act of 2005 (DRA) (PL 109-171); the Tax Relief and Health Care Act of 2006 (TRHCA) (PL 109-432); the Medicare, Medicaid, and SCHIP Extension Act of 2007 (MMSEA) (PL 110-173); and the Medicare Improvements for Patients and Providers Act of 2008 (MIPPA) (PL 110-275). Examples of key statutory and regulatory developments follow below.

The 75 Percent Rule

It has been stated that, “No governmental requirement related to the furnishing of inpatient rehabilitation services has generated more controversy than the criteria for being classified as an inpatient rehabilitation facility—the so-called ‘75 Percent Rule’” (

16). In the Final Rule implementing the Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act of 1982 (TEFRA) in January 1984, the Secretary determined that, to qualify as an inpatient rehabilitation hospital or rehabilitation unit and therefore be distinguished from an acute care hospital, a facility must have “served an inpatient population of whom at least 75 percent required intensive rehabilitation services for one or more of 10 conditions specified in the regulations” within the most recent 12 month cost reporting period (

17). The August 7, 2001 Final Rule that implemented the IRF PPS did not change the procedures for classification as an IRF (

18). SNFs, by contrast, have no special requirements for offering rehabilitation services. There are also no specific program regulations or requirements for rehabilitation services that may be provided in an LTCH.

On June 7, 2002, the CMS declared a moratorium on enforcement of the 75 Percent Rule because it found the rule was being unevenly enforced by the various state Departments of Health and the Medicare Fiscal Intermediaries (FIs) (

19). The moratorium ended in FY 2004 when a new Final Rule for IRF classification was published, which expanded the original 10 conditions to 13 and provided that the 75% compliance threshold was to be phased-in over several years, becoming fully effective for cost reporting periods beginning on or after July 1, 2007. The Final Rule also phased out the use of specific

patient comorbidities as counting toward the required 75% compliance threshold (

20).

Implementation of the revised 75 Percent Rule created a serious barrier to access to PM&R services for patients in inpatient rehabilitation hospitals and units as seen in

Table 19-1.

This table makes it clear that there was a dramatic drop in the number of cases admitted to rehabilitation hospitals and units, and an increase in length of stay and payment per case which represents the more severely medically and functionally impaired patients who were admitted.

It spawned intensive legislative advocacy. In the DRA of 2006, Congress responded and delayed implementation of the 75 Percent Rule by 1 year (

21). After that moratorium expired, Congress subsequently passed the MMSEA of 2007, which indefinitely set the compliance threshold at 60% (

22). MMSEA also provided that patient comorbidities be permanently included in the calculations used to determine whether an IRF meets the compliance percentage. With this legislative provision in place, the focus then turned to implementation of the new 60 Percent Rule (

23). As a trade-off for achieving permanent relief on the 75 Percent Rule by establishing a statutory 60% compliance threshold, the field of medical rehabilitation experienced an adverse economic consequence when the MMSEA rolled back the IRF update factor to 0% in FY 2008 and held it a 0% for FY 2009. Freezing or reducing updates has become an increasingly prominent means of seeking Medicare cost savings (

24).

Payment Updates and Other Payment System Changes

Under the various PPS, and under the Physician Fee Schedule (PFS) for professional services provided under Part B of the Medicare program, reimbursement rates are to be updated annually. The update calculation is made during the rulemaking process based on the index or process provided for in the underlying statute. Commonly, however, legislation is proposed and enacted as a means to override the update formula or amount. Section 131 of the MIPPA of 2008, for example, substituted a positive update of 1.1% to payment rates under the Medicare PFS for the negative update that would have resulted from the application of the statutory formula.

Outpatient Therapy Caps

As a cost control measure, Section 4541 of the BBA of 1997 required the CMS to impose a cap on Medicare outpatient rehabilitation therapy services for outpatient physical, speech-language and occupational therapy services by all providers other than hospital outpatient departments. Because of their complexity and direct harm to Medicare beneficiaries, the therapy caps have been subject to a “series of moratoria” enacted by Congress to avoid the strict limit placed on access to outpatient rehabilitative care (

25). Most recently, Section 141 of MIPPA extended the exceptions process for therapy caps at least through December 31, 2009.

Medicare Recovery Audit Contractors

The Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 (MMA) established the Recovery Audit Contractors (RAC) program as a demonstration program to identify improper Medicare payments. The TRHCA of 2006 made the RAC program permanent and directed the CMS to expand the program to all 50 states by 2010. The RAC demonstration program as implemented in California by the contractor, PRG Shultz, resulted in numerous coverage denials based upon medical necessity reasons. Subsequently, the affected California providers appealed these denials and a large percentage (90%) of these denied coverage decisions were reversed when they were appealed, based on anecdotal reports from California IRF providers. Specifically, 6% of the overpayments collected under the demonstration program through March 27, 2008 were from IRFs (

26). Of those cases, 94% were deemed medically unnecessary services or settings (

27). The number of claims

in California with overpayments less cases overturned on appeal as of March 27, 2008 was over 4,480 (

28). However, upon a subsequent review by a different CMS contractor, nearly 40% of the cases denied by the California RAC demonstration contractor were found to be incorrect (

29). In implementing the program nationwide, CMS regulations relating to medical necessity denials and appeals remain a key issue (

30). Legislation was introduced in the 110th Congress to impose a moratorium on the nationwide rollout of the RAC program but did not advance (

31). Legislation requiring enhanced oversight and accountability of RACs is anticipated in the 111th Congress.

Quality of Care

As part of ongoing initiatives to refocus payment incentives toward quality, CMS has already implemented a “pay for reporting” system for physicians where payment rates are tied to the reporting of quality measures. MIPPA made the Physician Quality Reporting Initiative permanent and authorized incentive payments through 2010. A potential next step is “pay for quality” where “providers would not only be rewarded for reporting quality activities but their payment would also be increased or decreased depending on how well they perform on these quality measures” (

32). Given the pervasive influence of the Medicare program, any such reimbursement mechanism can be expected to influence practice for all patients, regardless of payer. Payment system reform will likely include enhanced performance outcome measurements applicable to rehabilitation and LTCH.

THE PERVASIVE INFLUENCE OF MEDICARE AND MEDICAID

Given their scope of coverage, the Medicare and Medicaid programs have a profound influence on the practice of PM&R. This section sets forth the structure and features of each program.

The Medicare Program

Prior to the passage of the Medicare program, physicians practiced primarily in their offices and some in the hospitals and units providing medical rehabilitation services. Payment came from some insurance companies, private pay, and some state programs (

33).

The original Medicare and Medicaid programs were enacted in 1965 through Titles XVIII and XIX, respectively, of the Social Security Act. The Medicare system was originally administered by the Social Security Administration, but in 1977 management was transferred to the Health Care Financing Administration, which was renamed the CMS in 2001. CMS is part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and maintains a Web site at www.cms.hhs.gov.

Beneficiaries become eligible for Medicare by virtue of age (65 or older), disability, or if they have end-stage renal disease (ESRD) (

34). Medicare has four parts which describe and cover various aspects of the program. Medicare Part A and Part B are referred to as the original Medicare program, or the FFSs program. Medicare Part C is known as Medicare Advantage (MA) and gives beneficiaries the option to receive their Medicare benefits through managed care and private health insurance plans. Medicare Part D provides a prescription drug benefit (

35).

The programs have grown exponentially since inception. Short-term Medicare growth is reflected below (

Table 19-2).

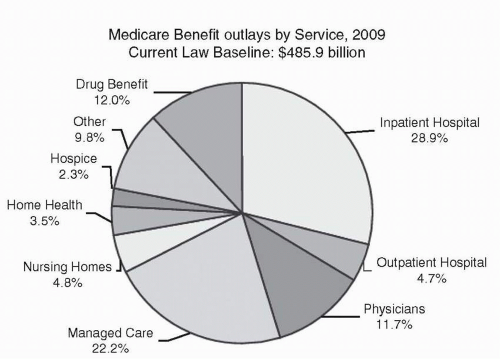

Medicare payments for federal FY 2009 were estimated in the President’s FY 2009 budget at $485.9 billion. The chart below displays the Medicare payments, known as outlays, estimated for FY 2009 (

Fig. 19-1).

Medicare Part A

Medicare Part A, in general, covers inpatient hospital services, critical access hospitals, SNFs (not including custodial or long-term care), hospice care, and the Part A portion of HH care and services. Part A thus covers the services provided in inpatient medical rehabilitation hospitals and units, long-term acute care hospitals, psychiatric hospitals, cancer hospitals, and children’s hospitals (

36).

People with over 40 quarters of covered employment are entitled to Part A without paying a premium, but most covered services require a beneficiary co-payment or coinsurance (

37).

In 2009, beneficiaries paid a $1,068 deductible for a hospital stay of 1 to 60 days and $133.50 daily coinsurance for days 21 to 100 in an SNF (

38). Part A is financed through a payroll tax.

The Social Security Act also provides for the enrollment, subject to payment of a monthly premium, of individuals who do not meet the requirement of 40 quarters of covered employment and are not otherwise eligible (

39). CMS estimates that approximately 588,000 enrollees voluntarily enrolled in Medicare Part A by paying a monthly premium of $433 for CY 2009 (

40).

Under Part A, providers are paid on the basis of a PPS specific to that provider. For example, acute care hospitals are paid per discharge under the inpatient prospective payment system (IPPS) using a classification system called Medicare Severity Diagnosis Related Groups (MS-DRGs) based on data from a series of ICD-9-CM codes (

41). Notably, on January 16, 2009, the Department of HHS published the Final Rule on the adoption of ICD-10-CM, the new diagnosis coding system that is being developed as a replacement for ICD-9-CM with a compliance date of October 1, 2013 (

42).

Inpatient rehabilitation hospitals and units are paid per discharge through the IRF PPS using a classification system known as Case Mix Groups (CMGs) which are derived from information collected on the inpatient rehabilitation facilities patient assessment instrument (

43). SNFs are paid on a per diem basis under the SNF PPS, using a classification system known as the Resource Utilization Groups which are based on information taken from the data collection instrument known as the Minimum Data Set (

44). Home health agencies (HHA) are paid per episode on the basis of the home health prospective payment system which uses a classification system known as the home health resource groups which are derived from information on the data collection known as the Home Health Outcome and Assessment Information Set (

45).

LTCHs are paid also on a per-discharge basis through the long-term care prospective payment system using a case mix classification system known as the Medicare Severity Long-Term Care Diagnosis Related Groups. However, like the acute inpatient hospitals, there is no separate patient assessment instrument. The information entered on the billing— specifically the ICD-9-CMs—determines the MS LTC DRG which specifies the payment rate.

In policy arenas, each payment system and provider is referred to as a “silo of care.” There is growing interest in consolidating these into one PPS. The Post Acute Care Reform Plan developed by CMS sets an “ultimate goal of site neutral payment for PAC [postacute care] services” (

46).

In addition, in December 2008, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) released

Budget Options Volume I: Health Care. This document outlines a number of proposals for reforming Medicare. Option 30 proposes to bundle payments for hospital and postacute care. Under this option, Medicare would pay a single, bundled rate to an inpatient hospital that includes the cost of postacute care based on the average cost for a specific MS-DRG across all current postacute settings (

47). This option is projected to save the Medicare program nearly $19 billion over the 10-year budget window. This proposal was echoed in the President’s FY 2010 Budget Outline,

A New Era of Responsibility: Renewing America’s Promise (

48). The significance of these developments is discussed further below.

Medicare Part B

Part B of Medicare is known at Supplementary Medical Insurance. It covers physician services including all specialty areas (

49). Physician services are paid on the basis of the PFS (

50). Physical therapists, occupational therapists, and speech-language pathologist services are also covered under Part B and paid under the PFS (

51). Part B additionally covers outpatient services such as the therapy services mentioned above and other outpatient services including certain laboratory services, preventive exams and screening, shots, durable medical equipment, prosthetics and orthotics and supplies, comprehensive outpatient rehabilitation facilities, and certain HH care services (

52). Hospital outpatient services are paid on a separate outpatient prospective payment system using a classification system known as Ambulatory Patient Classifications, which combines services that are clinically similar and similarly resource-intensive (

53). Durable medical equipment is paid according to a fee schedule separate from the PFS (

54).