Surgical Treatment of Partial Thickness Rotator Cuff Tears

John E. Conway

Steven B. Singleton

INTRODUCTION

The most common clinical and surgical findings in the injured shoulder of the overhead athlete include posterior partial thickness articular surface rotator cuff tears, type 2 anterior-to-posterior superior labrum avulsions (SLAP lesions), posterosuperior labrum tears, posteroinferior labrum tears or avulsions, anteroinferior glenohumeral laxity, hypertrophic subacromial bursa, excessive glenohumeral external rotation, deficient glenohumeral internal rotation, and scapular muscle dysfunction (1, 2, 3). Although our recognition and understanding of some of the conditions that are responsible for these findings have increased, there is still much about the throwing and overhead shoulder that remains unknown.

Recently, a higher level of awareness, combined with improvements in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) techniques, has made it possible to document extensive intratendinous delamination of the superior segment of the infraspinatus tendon (4, 5, 6). The most appropriate method to surgically manage these posterior, articular surface, intratendinous rotator cuff tears (PAINT lesions) found in throwing and other overhead athletes is uncertain. It is therefore a challenge for the treating surgeon to maintain reasonable expectations with regard to both the need to restore rotator cuff function and the potential to regain rotator cuff integrity.

PATHOMECHANICS

In 1985, Andrews and colleagues (7) described partial thickness, articular surface rotator cuff tears in a large group of overhead athletes. The occurrence and location of these tears were initially explained by the presence of excessive eccentric forces acting on the articular surface of the posterior rotator cuff during the deceleration segment of the throwing motion (7, 8, 9). It is commonly thought that other physiologic and biomechanical processes are also involved.

In the fully cocked overhead throwing position, the humerus is abducted 60 to 70 degrees on the glenoid and is in maximal external rotation. Scapular elevation produces the remainder of arm abduction and glenohumeral extension in the horizontal plane occurs in varying degrees. Arthroscopic, MRI, and cadaver research data have shown that when the shoulder is in this position, the greater tuberosity, the articular surface of the posterior supraspinatus tendon, and the articular surface of the superior infraspinatus tendon are compressed against the posterosuperior edge of the glenoid rim and labrum (4,10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20). This contact between intraarticular bone and soft tissue structures is described by the term internal impingement (10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18). Walch (11), Jobe (17), and McFarland (15) have shown that this contact may often be physiologic and occur in the absence of glenohumeral instability. However, excessive anterior glenohumeral laxity, glenohumeral external rotation, and glenohumeral horizontal extension probably increase the internal contact forces when the shoulder is in the late cocking and acceleration segments of the throwing motion (10,17,18,21). A detailed discussion of this condition is contained in Chapter 9.

Whereas internal impingement contact almost certainly contributes to the creation of posterior, articular-surface rotator cuff tears, this contact alone does not completely explain the presence of the rotator cuff tear or the constellation of additional findings in the injured overhead athlete’s shoulder. Other factors probably include intrinsic tendon degeneration, local tissue hypovascularity (22), anteroinferior glenohumeral instability (10,23), rotator interval and coracohumeral ligament laxity (21), subacromial outlet impingement (24,25), superior labrum-biceps tendon complex injuries (3,26, 27, 28, 29), posterior capsule contracture and internal rotation deficit (14,26,27), humeral retroversion (30), trunk, scapula and shoulder muscle dysfunction (31), excessive eccentric forces (7,8), neurologic conditions, improper mechanics, and far too much throwing or other repetitive overhead activity.

PAINT LESIONS

Over the last decade, the unique partial articular rotator cuff tear pattern recognized in throwers and other overhead athletes has been better defined (1,4,5,10, 11, 12, 13,20,32). In

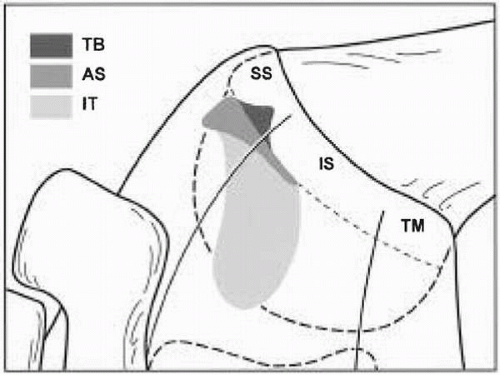

our opinion, this is best described as an L-shaped, partial thickness, articular surface tear occurring at the junction of the posterior supraspinatus tendon and the superior infraspinatus tendon (Fig. 10-1). The posterior edge of the tear is typically mobile and often appears as a flap of tendon extending into the joint. The tendon-from-bone segment of the tear is greatest in depth within the posterior supraspinatus tendon; and from this defect, the tear frequently extends well medial into the middle layers of the infraspinatus tendon (Fig. 10-2). This tear pattern differs from partial thickness, articular surface tears associated with primary outlet impingement principally in location. Even though the term PASTA (partial articular side tendon avulsion) lesion (33) has been used to describe articular surface tears in an older age patient population, we prefer the term PAINT lesion for throwers and other overhead athletes to emphasize the more posterior location and intratendinous involvement of these tears.

our opinion, this is best described as an L-shaped, partial thickness, articular surface tear occurring at the junction of the posterior supraspinatus tendon and the superior infraspinatus tendon (Fig. 10-1). The posterior edge of the tear is typically mobile and often appears as a flap of tendon extending into the joint. The tendon-from-bone segment of the tear is greatest in depth within the posterior supraspinatus tendon; and from this defect, the tear frequently extends well medial into the middle layers of the infraspinatus tendon (Fig. 10-2). This tear pattern differs from partial thickness, articular surface tears associated with primary outlet impingement principally in location. Even though the term PASTA (partial articular side tendon avulsion) lesion (33) has been used to describe articular surface tears in an older age patient population, we prefer the term PAINT lesion for throwers and other overhead athletes to emphasize the more posterior location and intratendinous involvement of these tears.

Many factors contribute to the articular surface location of these tears. The articular surface of the rotator cuff has fewer arterioles and overall less vascularity than the bursal surface. The articular surface has a higher modulus of elasticity and therefore greater stiffness than the bursal surface. Eccentric forces tend to be concentrated more in the articular surface. Finally, the articular surface has a less favorable stress-strain curve than the bursal surface. When combined with the rotator cuff and glenoid contact forces produced by internal impingement, these factors probably explain the occurrence, the location, and the predominance of articular surface rotator cuff tears in overhead athletes (8,10, 11, 12,18,20,30,32,34, 35, 36, 37, 38). The cause of the intratendinous delamination in these athletes is less clear.

In 1992, Walch and colleagues (13) reported eight rotator cuff tears in 14 throwers and noted that “some tears

extend into the depth of the tendon, dissecting into two layers.” With improved MR imaging methods, extension of the articular surface tears into the middle layers of the infraspinatus tendon is increasingly recognized in these athletes diagnosed with internal impingement (4, 5, 6,35,39). It is likely that the tangentially and perpendicularly opposed vector forces acting on the five-layered architecture of the rotator cuff tendon generate shear stress within the middle layers and thereby create the intratendinous tears (34, 35, 36,40). Additionally, the coracohumeral ligament has been shown to blend with the articular surface of the anterior supraspinatus tendon (21). Acting as a primary restraint to external rotation in the late cocking segment of the throwing motion, this ligament probably further increases the shear forces in the middle layers of the posterosuperior rotator cuff tendons.

extend into the depth of the tendon, dissecting into two layers.” With improved MR imaging methods, extension of the articular surface tears into the middle layers of the infraspinatus tendon is increasingly recognized in these athletes diagnosed with internal impingement (4, 5, 6,35,39). It is likely that the tangentially and perpendicularly opposed vector forces acting on the five-layered architecture of the rotator cuff tendon generate shear stress within the middle layers and thereby create the intratendinous tears (34, 35, 36,40). Additionally, the coracohumeral ligament has been shown to blend with the articular surface of the anterior supraspinatus tendon (21). Acting as a primary restraint to external rotation in the late cocking segment of the throwing motion, this ligament probably further increases the shear forces in the middle layers of the posterosuperior rotator cuff tendons.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree