Fig. 1

Cam impingement occurs with hip flexion as the bony prominence of the nonspherical portion of the femoral head (cam lesion) glides under the labrum engaging the edge of the articular cartilage and results in progressive delamination. Initially, the labrum is relatively preserved, but secondary failure occurs over time (© J. W. Thomas Byrd, reprinted with permission)

Cam impingement is classically attributed to a slipped capital femoral epiphysis, resulting in a bony prominence of the anterior and anterolateral head/neck junction. However, the most common cause is the pistol grip deformity, attributed to a developmental abnormality of the capital physis during growth. The exact etiology is unclear; it may represent premature asymmetric closure of the physis, and it has been postulated that this could be due to late separation of the common proximal femoral growth plate that forms the physis of the greater trochanter and femoral head [2].

Femoroacetabular impingement is still incompletely understood. The pathomechanics explain the observations of secondary joint pathology caused by the impingement. However, some individuals with impingement-shaped hips may never become symptomatic due to secondary damage. Thus, it is possible to have impingement morphology without impingement pathology. The arthroscope has become invaluable in the treatment algorithm for patients with FAI. Arthroscopic observations on the secondary articular and labral damage associated with pathological impingement dictate the need for correcting the underlying bony abnormalities.

Patient Selection

History and Physical Examination

Patients with cam impingement have typical hip joint-type symptoms [3]. The onset may be gradual or associated with an acute episode, which is the culmination of altered wear developing over a protracted period of time. Patients with cam impingement usually have reduced joint motion which can result in other secondary disorders. Athletes compensate with increased pelvic motion, often resulting in problems with athletic pubalgia [4]. More stress is placed on the lumbar spine, resulting in concomitant lumbar disease.

Pain with flexion, adduction, and internal rotation is almost uniformly present and is referred to as the “impingement test” (Fig. 2) [5]. However, in this author’s experience, this maneuver is uncomfortable for most irritable hips, regardless of the underlying etiology, and thus is not specific for impingement. Laterally based cam lesions may result in painful abduction or external rotation (Fig. 3). Internal rotation of the flexed hip is usually diminished but may be preserved in some patients (Fig. 4). Limited range of motion may be present bilaterally as the morphological variation is often present in both hips.

Fig. 2

The impingement test is performed by provoking pain with flexion, adduction, and internal rotation of the symptomatic hip (© J. W. Thomas Byrd, reprinted with permission)

Fig. 3

Abduction and external rotation may elicit pain with laterally based cam lesions (© J. W. Thomas Byrd, reprinted with permission)

Fig. 4

Internal rotation is checked with the hip in a 90° flexed position (© J. W. Thomas Byrd, reprinted with permission)

Diagnostic Imaging

Radiographs are essential to the routine evaluation of impingement. A well-centered AP pelvis X-ray is important for assessing the acetabular indices of pincer impingement but also allows observations on the cam lesion by comparing both hips (Fig. 5) [6]. The epicenter and shape of the cam lesion are variable. Thus, while the 40° Dunn view has been reported as the best image, in this author’s experience, no single lateral radiographic view is reliable for optimally assessing the cam lesion in all cases (Fig. 6) [7]. Sometimes the cam lesion is more anteriorly based and sometimes more lateral. The characteristic feature is loss of sphericity of the femoral head. The alpha angle has been described to quantitate this observation (Fig. 7) [8]. However, imaging will under interpret this measurement unless it catches the maximal location of the cam lesion. No studies have shown a significant correlation between the amount of alpha angle correction and the results of surgery, indicating that there may be other factors at play; but higher alpha angles have been associated with more clinically relevant lesions [9, 10].

Fig. 5

A properly centered AP radiograph must be controlled for rotation and tilt. Proper rotation is confirmed by alignment of the coccyx over the symphysis pubis (vertical line). Proper tilt is controlled by maintaining the distance between the tip of the coccyx and the superior border of the symphysis pubis at 1–2 cm (© J. W. Thomas Byrd, reprinted with permission)

Fig. 6

The frog lateral radiograph is convenient because it is simple to obtain in a reproducible fashion. The cam lesion (arrow) is evident as the convex abnormality at the head/neck junction where there should normally be a concave slope of the femoral neck (© J. W. Thomas Byrd, reprinted with permission)

Fig. 7

The alpha angle is used to quantitate the severity of the cam lesion. A circle is placed over the femoral head. The alpha angle is formed by a line along the axis of the femoral neck (1) and a line (2) from the center of the femoral head to the point where the head diverges outside of the circle (arrow) (© J. W. Thomas Byrd, reprinted with permission)

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and gadolinium arthrography with MRI (MRA) aid in assessing secondary damage to the articular cartilage and labrum associated with cam impingement [11]. These studies are better at detecting labral pathology and less often reveal the severity of articular involvement. Alpha angle can again be recorded but is still variable depending on whether the cross-sectional images catch the maximal location of the cam lesion.

Computed tomography with 3-D reconstruction provides great clarity in evaluating the shape, size, and location of the cam lesion. This is quite valuable for the arthroscopic management of this condition. Exposure of the abnormal bone is simplified by knowing its exact appearance.

Indications/Contraindications

The indication for hip arthroscopy is imaging evidence of intra-articular pathology amenable to arthroscopic intervention, or sometimes simply recalcitrant hip pain that remains refractory to efforts at conservative treatment, keeping in mind that imaging studies may often underestimate the severity of intra-articular pathology. Correction of the cam lesion is performed, especially when there is arthroscopic evidence that it is responsible for the concomitant joint pathology. This secondary joint damage is best characterized by failure of the anterolateral acetabular articular surface. The failure is most typically represented by articular delamination with the peel-back phenomenon but, earlier in the disease process, may be characterized by simply deep closed Grade I articular blistering, referred to as the wave sign [12].

It is this author’s opinion that simply radiographic findings of impingement, in the absence of clinical findings of a joint problem, are not an indication for arthroscopy. Some individuals with impingement morphology may function for decades without developing secondary joint damage and symptoms. For some it is unclear when, or if, they will develop problems warranting surgical intervention. For example, many individuals may present with symptoms in one hip when radiographic findings of impingement are present in both. While intervention in the asymptomatic joint would not be appropriate, it is important to educate the patient about warning signs of progressive joint damage. It is a clinical challenge in the decision not to intercede too early or too late. In this author’s experience, 93 % of patients undergoing arthroscopy for cam impingement demonstrate Grade III and Grade IV articular damage, reflecting that the disease process is already substantially advanced at the time of intervention [1].

Objective contraindications include advanced disease states characterized by Grade 3 Tonnis changes, or less than 2 mm remaining joint space [13–15]. Prominent cam lesions, almost by definition, constitute a Grade 2 Tonnis change and broad spectrum of disease. Larson has subcategorized Tonnis 2 into those with greater or less than 50 % joint space remaining, showing poorer results among those with less than 50 % residual space [15]. Subjective contraindications may include the patient’s expectations of surgery. If the patient has unreasonable goals of what the procedure may accomplish, then surgery may not be the best option. Also, in the presence of secondary degenerative disease, the potential advantages of a joint preserving procedure must be weighed against the high level of satisfaction associated with joint arthroplasty.

Conservative Treatment

Conservative management begins with an emphasis on early recognition of the underlying impingement disorder. The mainstay of treatment is identifying and modifying offending activities that precipitate symptoms. Some individuals can modify their lifestyles and stabilize the process for years. Efforts can be made to optimize mobility of the joint, but these are only modestly effective since motion is limited by the bony architecture which cannot be corrected with manual techniques. Decompensatory disorders are those secondary problems that develop as individuals struggle to compensate for the chronic limitations imposed by the impingement. A conservative strategy must include assessment and treatment of the secondary problems, which can contribute substantially to the patient’s symptoms.

For patients with degenerative disease, treatment may simply be lifestyle modifications to keep the symptoms manageable. For athletes pushing the joint beyond its diminished physiologic limitations, a specific program becomes more important. Optimizing core strength can aid in regaining the athlete’s ability to properly compensate. Loading of a flexed hip can be particularly destructive in the presence of impingement; thus, repetitive training activities such as squats and lunges should be avoided, or modified, to limit hip flexion.

Surgical Technique

The procedure begins with arthroscopy of the central compartment to assess for the pathology associated with cam impingement. This is carried out with the standard supine three-portal technique that has been well described in the literature (Fig. 8) [16–18]. The characteristic feature of pathological cam impingement is articular failure of the anterolateral acetabulum. The femoral head remains well preserved until late in the disease course. Early stages of the disease are characterized by closed Grade I chondral blistering, which sometimes must be distinguished from normal articular softening (Fig. 9). This author’s experience has been that most patients already have Grade III or Grade IV acetabular changes by the time of surgical intervention [1]. The articular surface is seen to separate or peel away from its attachment to the labrum (Fig. 10) and is caused by the shear effect of the cam lesion. The labrum may be relatively well preserved but, with time, progressive fragmentation occurs.

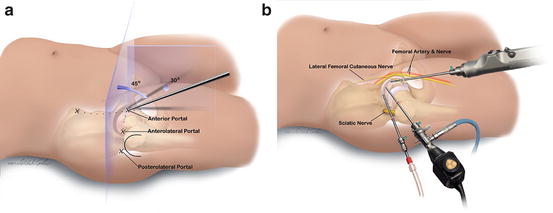

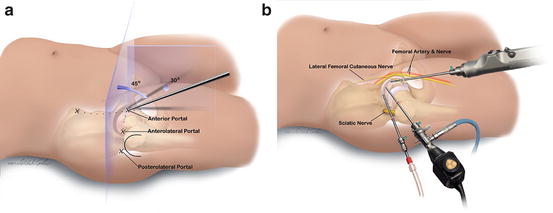

Fig. 8

(a) The site of the anterior portal coincides with the intersection of a sagittal line drawn distally from the anterior superior iliac spine and a transverse line across the superior margin of the greater trochanter. The direction of this portal courses approximately 45° cephalad and 30° toward the midline. The anterolateral and posterolateral portals are positioned directly over the superior aspect of the trochanter at its anterior and posterior borders. (b) The relationship of the major neurovascular structures to the three standard portals is illustrated. The femoral artery and nerve lie well medial to the anterior portal. The sciatic nerve lies posterior to the posterolateral portal. The lateral femoral cutaneous nerve lies close to the anterior portal. Injury to this structure is avoided by using proper portal placement. The anterolateral portal is established first because it lies most centrally in the safe zone for arthroscopy (© J. W. Thomas Byrd, reprinted with permission)

Fig. 9

Pathological chondral blistering (asterisk) is being probed from the anterior portal of this right hip. This indicates sublaminar shearing of the articular cartilage associated with pathological cam impingement. Unroofing the blister may reveal partial or full-thickness articular loss (© J. W. Thomas Byrd, reprinted with permission)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree