Surgical Management of Medial Collateral Ligament Injuries

Bryson Patrick Lesniak

LCDR Scott T. King

Christopher D. Harner

INTRODUCTION

The medial collateral ligament (MCL) is the most commonly injured ligament in the knee (3, 4, 5,8,10). It generally results from trauma to the knee following valgus with or without a rotational force applied. MCL injuries present as an isolated injury or commonly in combination with injury to the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), posterior cruciate ligament (PCL), or both. The MCL has a relative increased ability to heal primarily without surgical intervention compared to the other ligaments of the knee. There are certain MCL injuries, mostly in combination with concomitant ligamentous injuries that do not reliably heal nonoperatively and leave patients with significant joint instability. The purpose of this chapter is to delineate which patients are at risk and how they are treated.

ANATOMY

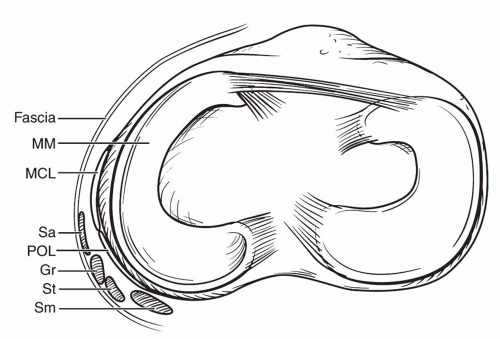

Warren et al. (13) described the medial side of the knee to be anatomically divided into three layers. Layer I includes the superficial sartorial fascia bordered anteriorly by the patella tendon and posteriorly by the popliteal fossa. Anteriorly layer I merges with layer II. The gracilis and semitendinosus tendons can be separated from layer I superficially and layer II deep to it. Layer II is composed of the superficial MCL, which merges with layer III at the posteromedial corner of the knee. Layer III is deep to the superficial MCL and consists of the capsule of the knee with a thickened portion termed the middle capsular ligament (Fig. 37.1).

The MCL, and more specifically the superficial MCL, is the primary resistance to valgus force applied to the knee (4,6,14). Studies have shown the MCL provides 57% of the total restraint at 5 degrees and 78% of the total restraint at 25 degrees of flexion. Near full extension, the posterior medial capsular structures provide increased medial stabilization. Based on cadaveric studies, Grood et al. (4) found that a 5 to 8 mm increase in medial laxity clinically is indicative of a complete MCL injury (4).

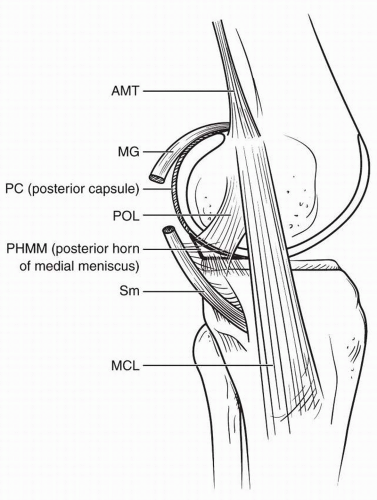

The superficial MCL is the largest structure in the medial aspect of the knee. It is between 10 and 12 cm long and 1.5 cm wide (2,9,11,14). The femoral attachment of the superficial MCL is an average of 3.2 mm proximal and 4.8 mm posterior to the medial epicondyle (9). There are two separate tibial attachments (1,9,12). The proximal tibial attachment is primarily to the semimembranosus tendon (9). The distal tibial attachment is approximately 6 cm distal to the joint line, just anterior to the posteromedial crest of the tibia (1,9,12). The deep MCL consists of the medial capsular, posterior oblique, meniscofemoral and meniscotibial ligaments (Fig. 37.2).

CLASSIFICATION

MCL injuries are classified according to chronicity, the extent of disruption of the ligament, the amount of joint laxity, and location of injury. An acute injury is defined as an injury that occurred within the past 3 weeks. Valgus stress testing at 0 and 30 degrees of knee flexion allows estimation of the amount of laxity. At 30 degrees of knee flexion, a grade 1 injury is <5 mm of medial joint opening, grade 2 is 5 to 10 mm of laxity, and grade 3 is >10 mm. Any laxity at 0 degree is an ominous sign as there are likely associated injuries such as a cruciate tear or a posteromedial capsular injury. Chronic MCL injuries typically occur when nonoperative management of a grade 3 MCL injury fails and is typically 6 weeks or greater from time of the injury.

Location of an MCL injury can be described as a femoral avulsion, tibial avulsion, or midsubstance tear. This is an important consideration because complete tibial sided MCL tears (tears that involve both the deep and the superficial components) often do not heal. The reason for this lack of healing is likely interruption of the tendon-bone interface by synovial fluid (15).

HISTORY/PRESENTATION

Injury to the MCL involves an isolated valgus force to the knee, or a valgus combined with a rotational force. It is usually the result of a sports-related impact injury or a twisting noncontact injury. When rotational

injury is suspected, concomitant injury to the posteromedial corner structures and/or the ACL should be considered. The patient will present with varying degrees of swelling, pain, instability, and loss of motion. Location of swelling can be variable. An isolated MCL tear may only have swelling at the medial aspect of the knee. A hemarthrosis may be present if there is injury to the deep MCL and capsule, or if there is other associated intra-articular pathology. Studies have found up to 80% of MCL injuries have additional ligamentous injury (3).

injury is suspected, concomitant injury to the posteromedial corner structures and/or the ACL should be considered. The patient will present with varying degrees of swelling, pain, instability, and loss of motion. Location of swelling can be variable. An isolated MCL tear may only have swelling at the medial aspect of the knee. A hemarthrosis may be present if there is injury to the deep MCL and capsule, or if there is other associated intra-articular pathology. Studies have found up to 80% of MCL injuries have additional ligamentous injury (3).

PHYSICAL EXAM

The injured knee should be examined completely and compared with the contralateral knee. This includes a thorough neurovascular examination. Although potentially difficult, the patient should be relaxed to achieve a useful physical exam. Tenderness along the MCL should be assessed by palpation and note made of whether pain can be localized to a specific region of the MCL. In order to isolate the MCL on exam, a valgus force in the coronal plane should be applied while avoiding any rotational component. The MCL should be tested at 0 and 30 degrees of flexion (Figs. 37.3 and 37.4). As previously stated, increased laxity to valgus stress in full extension is an ominous sign as it implies possible injury to a cruciate ligament and/or posteromedial capsular structures. Flexion of the knee reduces the secondary restraint of the posterior capsule and better isolates the MCL. The ACL and the PCL provide secondary restraint to varus and valgus stress, so the knee should remain stable with stress at zero degree if the cruciate ligaments are intact, even in the setting of MCL injury. The ACL, PCL, LCL, and posterolateral corner should all be examined to determine the severity and pattern or the injury (Figs. 37.5 and 37.6).

The endpoint of varus and valgus stress to the knee should be noted. A complete tear of the MCL may or may not have an endpoint detected with valgus stress. If there is any uncertainty, comparison to the contralateral knee can provide further confirmation of the injury.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree