Femoroacetabular Impingement

Zackary D. Vaughn

Marc R. Safran

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

Background

The pathology of femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) was initially described (1992) and published (1995) by Ganz, but first presented in the English literature in 1999 (1). Although FAI is a three-dimensional disorder with varying degrees and anatomic locations of pathologies, two main forms of impingement have been described. The first description was of an abnormality in acetabular overcoverage, known as pincer impingement. This results in a crushing of the labrum and acetabular rim against the femoral head-neck junction, which can lead to complex degenerative labral tearing from the crushing mechanism, edge loading of acetabular rim, calcific changes to the labrum with possible labral ossification and a type of “contrecoup” lesion of chondromalacia in the posterior aspect of the acetabulum and femoral head from subtle subluxation of the femoral head as it levers anteriorly (2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7).

The second form of FAI described is that of cam impingement, resulting from a bony abnormality of femoral head-neck junction with the loss of normal femoral head sphericity and femoral head-neck offset. This abnormal area of bone impacts the acetabulum and labrum leading to labral-chondral separation and a delamination of articular cartilage at the acetabular periphery. Although characterized as separate entities, it is most common to have both types of FAI present, although one form may predominate (2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7). The goal in the treatment of FAI is to restore the normal anatomy of both the acetabulum and the femoral head-neck junction, while also treating any associated pathology of the labrum or articular cartilage. Controversy has existed as to the best means to accomplish this, as both open and arthroscopic techniques have been described. The recent advances in hip arthroscopy have made the arthroscopic treatment of both the intra-articular and extra-articular components of FAI a safe and reliable procedure in experienced hands.

Indications

Hip arthroscopy has seen a recent increase in interest since the 1980s. Subsequently, arthroscopy of the hip has been in a constant state of evolution with the advent of new instrumentation, improved knowledge of safety and techniques, and increasing surgeon experience, allowing for an expanding list of indications. Arthroscopic treatment for FAI is indicated in patients with a diagnosis of symptomatic FAI with or without associated labral or chondral injury. Some authors believe that surgery for FAI should be performed to prevent arthritis, even if it is asymptomatic. However, currently, no evidence exists that surgical correction of the FAI anatomy will prevent the development of arthritis, even though FAI may be a major cause of premature degenerative arthritis. Though not everyone with the anatomy of FAI will develop arthritis, there is no evidence that surgery for FAI will prevent arthritis (9). It is likely that the combination of this underlying anatomic abnormality and various activities that require an extended range of motion, such as cycling, running, soccer, and martial arts, will result in the breakdown of soft tissues, resulting in symptomatic impingement. Therefore, we recommend that only the hip with symptoms that can be attributed to FAI should be treated, whether open or arthroscopic.

Contraindications

The arthroscopic treatment of FAI is contraindicated in any patient who has contraindications to general anesthesia or elective surgical interventions of any kind based on medical comorbid conditions or infections. Patients with evidence of significant degenerative changes on plain radiographs with joint space narrowing or a predominance of aching pain at rest due to arthritis are not likely to have significant benefit from arthroscopy. Surgical treatment of FAI should also be avoided in patients who do not obtain symptom relief with an intraarticular injection of local anesthetic and further evaluation should be directed at other diagnoses.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

History

Patients with symptomatic FAI generally present with an insidious onset of aching pain in the hip and groin. Common aggravating activities include putting on or taking off shoes and socks, motions that generate deep flexion of the hip joint, sitting for prolonged periods of time, arising from a seated position, ascending or descending stairs or steep hills, sudden starts and stops, or any cutting and pivoting motion (10). The pain is typically made worse with impact activity and is described as originating from the groin, inguinal region, or deep within the joint (10). Patients may also note a gradual decrease in range of motion, particularly in flexion, adduction, and internal rotation (11). More abrupt onset of symptoms may be associated with a labral tear, labral-chondral separation, or a chondral flap, any of which can present with mechanical symptoms of painful locking, clicking, or catching.

Physical Examination

A complete review of the evaluation of the hip is beyond the scope of this chapter, but the reader is referred to references (12, 13, 14). A complete examination of the hip will include evaluating core and abdominal strength and ruling out pathology from the spine and knee. An evaluation of both stance and gait and inspection of the skin about the hip is the initial part of the exam. Trendelenberg and Ober tests are utilized to evaluate weakness and tightness of the hip abductors, respectively. Hip range of motion must be carefully documented in the supine position and related to the unaffected side. In patients with impingement, there is typically a limitation of internal rotation, particularly when the hip is flexed to 90 degrees. A positive impingement test is elicited with pain generated when the hip is brought to 90 degrees of flexion, adducted across the midline, and internally rotated (Fig. 47.1). Additionally, patients may have pain with a labral stress test (passive circumduction of the hip from abduction and external rotation with flexion, to a flexed, adducted, and internally rotated position) or with a resisted straight leg raise generating groin pain. These tests are often positive in FAI, both cam and pincer types, and also with other intra-articular pathology (12, 13, 14).

Imaging Studies

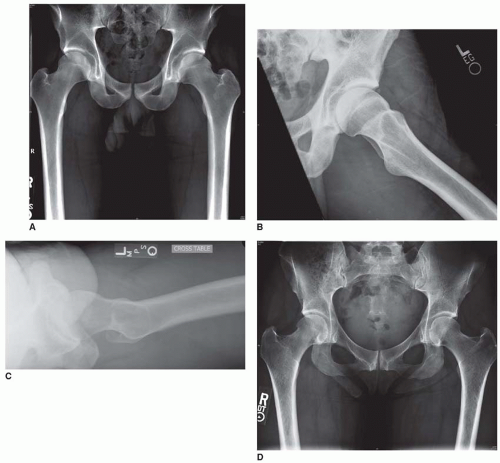

Plain radiographs including an appropriate AP pelvis with the coccyx centered 1-3 cm above the pubic symphysis (Fig. 47.2A) and a true cross-table lateral (Fig. 47.2C) of the affected hip are essential to evaluating patients with hip pain consistent with the impingement process. The cross-table lateral/Dunn view and modified Dunn view are true lateral views of the hip and are more useful to provide both information about the proximal femur and the acetabulum compared to the frog-lateral projection (Fig. 47.2B), which provides limited evaluation of the acetabulum while demonstrating the lateral proximal femur. On these images, the femoral head is generally symmetric and has a distinct femoral head-neck offset. The loss of this sphericity in the femoral head and neck region may be consistent with cam impingement (15, 16, 17) (Fig. 47.2A-C). This can be demonstrated

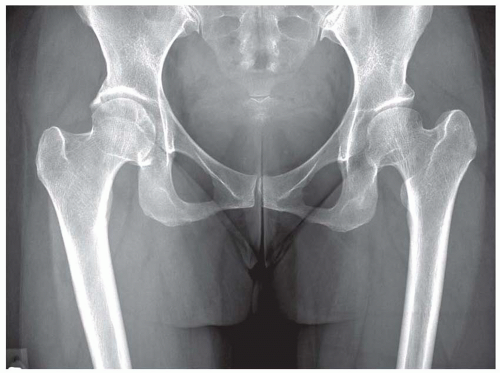

by a lack of concavity to the femoral head-neck junction on the AP view, appearing that the femoral head is not centered over the femoral neck. In some cases, a bony bump can be seen on the lateral view at the anterolateral femoral head-neck junction that may project beyond the femoral head or have a sharp transition or even a hook appearance to this area. Pincer impingement can also be well evaluated on these routine radiographs, demonstrating coxa profunda, protrusio, acetabular retroversion, and evidence of developmental dysplasia and arthritic changes. Coxa profunda is demonstrated on the AP pelvis when the floor of medial acetabulum is at or beyond the ilioischial line (Figs. 47.2D and 47.3). Protrusio is present when the most medial aspect of the femoral head is found to extend to or beyond the ilioischial line. The crossover sign is indicative of acetabular retroversion as the lines of the anterior wall and posterior wall are found to cross over one another on the properly positioned AP pelvis view (Fig. 47.2A). Dysplasia is evaluated with the lateral center edge angle of Wiberg measured on the AP view, or the anterior center edge angle of Lequesne measured on the false profile view of the pelvis. With either measurement, a value of <25 degrees is considered abnormal and a sign of dysplasia (Fig. 47.3).

by a lack of concavity to the femoral head-neck junction on the AP view, appearing that the femoral head is not centered over the femoral neck. In some cases, a bony bump can be seen on the lateral view at the anterolateral femoral head-neck junction that may project beyond the femoral head or have a sharp transition or even a hook appearance to this area. Pincer impingement can also be well evaluated on these routine radiographs, demonstrating coxa profunda, protrusio, acetabular retroversion, and evidence of developmental dysplasia and arthritic changes. Coxa profunda is demonstrated on the AP pelvis when the floor of medial acetabulum is at or beyond the ilioischial line (Figs. 47.2D and 47.3). Protrusio is present when the most medial aspect of the femoral head is found to extend to or beyond the ilioischial line. The crossover sign is indicative of acetabular retroversion as the lines of the anterior wall and posterior wall are found to cross over one another on the properly positioned AP pelvis view (Fig. 47.2A). Dysplasia is evaluated with the lateral center edge angle of Wiberg measured on the AP view, or the anterior center edge angle of Lequesne measured on the false profile view of the pelvis. With either measurement, a value of <25 degrees is considered abnormal and a sign of dysplasia (Fig. 47.3).

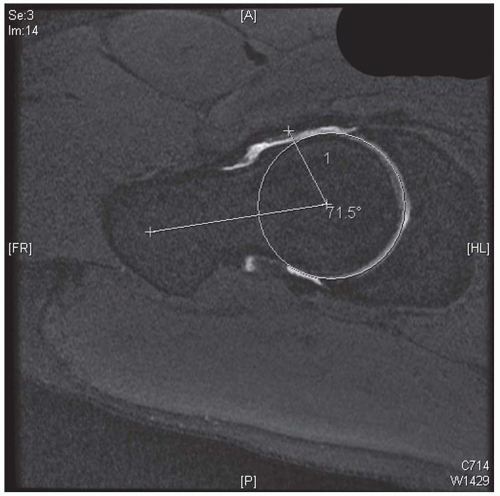

Additional imaging modalities include CT scans, particularly a 3D reconstruction series, and MRI sequences. The CT scan is helpful for demonstrating the bony anatomy involved in the impingement process, while the MRI, particularly an MR arthrogram with a small field of view for the hip, is beneficial in alpha angle measurement, demonstrating the cam lesion, labral tears, chondral lesions, and edema or cysts within the femoral neck. The alpha angle (Fig. 47.4) as described by Notzli to quantify the femoral head-neck junction offset is based upon measurements on a radially generated axial MRI sequence (18). Most surgeons use 55 degrees as a cutoff value for defining cam impingement; however, the accuracy of measurement, reproducibility of measurement, and the positive correlation between correction of this measurement and surgical outcomes have not been shown.

FIGURE 47.4 Is an example of an MRI from the basketball player in Figure 47.2, with the measurement of the alpha angle of 71 degrees. The alpha angle is measured as a line draw perpendicular to the narrow part of the femoral neck. A circle is drawn that most closely approximates the head size. A line is drawn from the center of the head to the point where the anterolateral femoral head exceeds the radius of the circle. The angle made by these two lines is the alpha angle. An angle <50 or 55 degrees is considered normal. (Figure used by permission of Marc R. Safran, MD.) |

Our imaging protocol for the evaluation of FAI is to obtain a proper AP pelvis, cross-table lateral view, and a dedicated hip MR arthrogram utilizing a small field of view, with the use of intra-articular gadolinium and local anesthetic. This injection helps confirm the intra-articular source of pain with the temporary relief of symptoms from the local anesthetic component (19).

SURGERY

The goals of surgery for FAI are to relieve the abutment between the femoral head-neck junction and acetabular rim, in addition to treating the associated pathology of labral tears and chondral lesions. While this may be done in the supine or lateral position, our preference is the supine position. The following will describe our preferred arthroscopic technique for acetabuloplasty for pincer impingement and cheilectomy (or femoral osteoplasty) for cam impingement.

Patient Positioning and Draping

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree