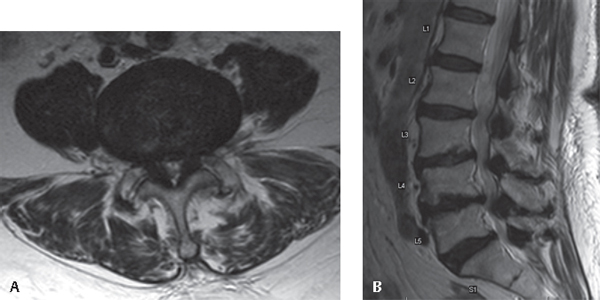

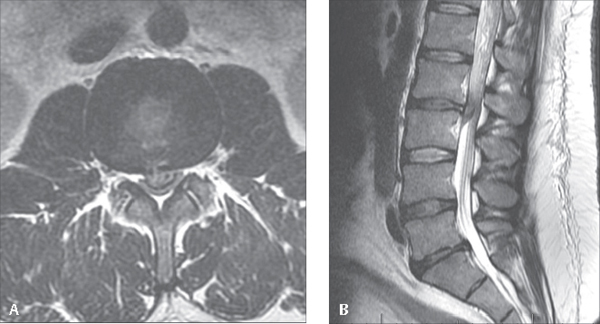

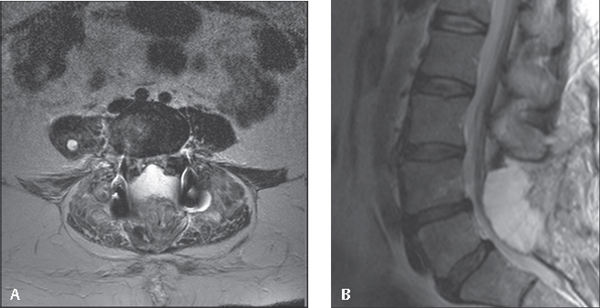

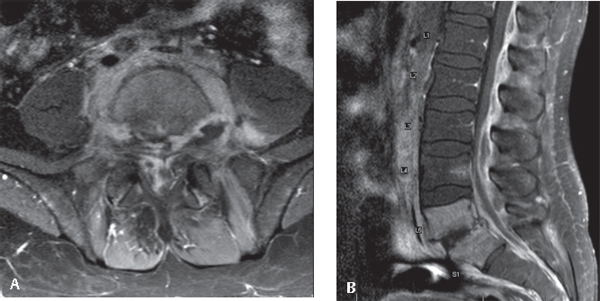

73 This chapter describes identification and management of situations that may require urgent or emergent decision making and possibly surgical intervention to prevent permanent neurologic injury. This chapter discusses the diagnosis, workup, and treatment of cauda equina syndrome, epidural hematoma, epidural abscess, incomplete neurologic deficit after traumatic injury, and progressive neurologic symptoms of spinal cord compression due to tumor. Cauda equina syndrome is characterized by a constellation of lower-extremity pain, motor weakness, radiculopathy, saddle anesthesia, and urinary/fecal dysfunction. The presentation is variable. Patients may complain of unilateral or bilateral symptoms. The most common cause of CES is a lumbar disk herniation. CES most frequently presents in the fourth or fifth decade of life. It can also occur in patients with a baseline stenotic spinal canal, resulting in chronic CES (Fig. 73.1A,B). Other causes of CES include epidural abscess, tumors, fractures, or hematomas. On examination, patients with CES may have variable sensory deficit, although classically CES has been associated with saddle anesthesia (numbness in the perineum and inner thighs in the area where one might sit on a saddle). Additional symptoms may include distal-extremity weakness, depressed lower extremity reflexes, and decreased sphincter tone. Patients should also have a postvoid residual volume check after urination as urinary retention can be the presenting symptom. A postvoid residual greater than 500 mL has been demonstrated to be associated with CES. The difficulty with a diagnosis of CES is the absence of absolute clinical diagnostic criteria. Therefore, patients presenting with complaints of any of the symptoms just discussed should undergo a careful neurologic examination to identify other signs and symptoms consistent with a diagnosis of CES. Any patients with symptoms suggestive of CES should undergo urgent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to identify the possible neural element in compression (Fig. 73.2A,B). Fig. 73.1 MRI images demonstrating chronic multilevel lumbar stenosis in a patient who experienced waxing/waning symptoms consistent with chronic CES. Ultimately, the patient underwent decompression from L3 to S1 with resolution of her symptoms of saddle anesthesia and lower-extremity motor weakness and partial resolution of associated urinary symptoms. (A) Axial (at L4–L5). (B) Sagittal. Although little debate exists regarding the need for urgent decompression, controversy remains regarding the timing of surgery. The prognosis of CES is generally poor, and a significant number of patients report long-term sphincter and sexual dysfunction. The best results have been reported with early surgery (within 24–48 hours of onset). Additionally, patients with incomplete symptoms, such as partially preserved continence or progressive motor loss, may have improved prognosis compared with patients with complete symptoms. The prognosis of patients with complete motor loss is generally poor. Regardless, decompression should be performed as soon as medically feasible. Fig. 73.2 MRI images demonstrating massive L2–L3 disk herniation in a patient who presented with urinary incontinence and bilateral lower extremity weakness. The patient underwent decompressive laminectomy with complete resolution of symptoms postoperatively. (A) Axial. (B) Sagittal. Epidural hematoma similarly presents with progressive neurologic symptoms referable to the level of involvement, which can be any spinal level (Fig. 73.3A,B). Patients often report sharp pain localized to the spine at the level where the hematoma forms, which is followed by progressive neurologic signs and symptoms. Epidural hematomas can be postsurgical, postprocedural (after epidural injection or spinal anesthesia), or spontaneous. A thorough history is essential to identify potential contributing factors, such as recent procedures, but also should include the use of anticoagulants or history of coagulopathy. Approximately one-half of patients with spontaneous epidural hematomas will have no obvious risk factors, although men in their sixth or seventh decade of life are most commonly affected. Additionally, patients with ankylosing spondylitis can develop epidural hematomas after relatively minor trauma. Patients presenting with a progressive neurologic deficit should undergo emergent imaging. Hematoma most commonly affects the dorsal aspect of the spinal canal. Multilevel surgery and preoperative coagulopathy have been identified as risk factors, while the use of postoperative drains does not seem to affect the incidence of postoperative epidural hematoma. Fig. 73.3 MRI images after L4–L5 posterior spinal decompression and fusion demonstrating large dorsal hematoma. The patient complained of postoperative tingling and weakness in the L5 distribution, which resolved with decompression. (A) Axial. (B) Sagittal. Diskitis and osteomyelitis cause nonspecific axial pain and often can be present for several months prior to diagnosis. Epidural abscess may occur spontaneously after untreated diskitis/osteomyelitis, although it can also occur iatrogenically after percutaneous spinal procedures. The clinical presentation of epidural abscess is dependent on the resultant spinal canal stenosis. Patients with mild stenosis may be asymptomatic, but patients with severe stenosis may develop symptoms of radiculopathy, myelopathy, numbness, weakness, or incontinence. The key factor in identifying epidural abscess is distinguishing nonmechanical back pain (worse at night, not activity related) and/or constitutional symptoms. In the worst-case scenario, patients may have meningitis due to the infection. Patients at risk for epidural abscess, diskitis, or osteomyelitis should have blood work to facilitate diagnosis of the infection (complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein) as well as blood cultures. Radiographs will demonstrate disk space narrowing in the early phases of diskitis/osteomyelitis. MRI should be performed with gadolinium, which will show rim-enhancement of the abscess (Fig. 73.4A,B). Epidural abscesses may result as a direct extension of osteomyelitis or diskitis or adjacent postsurgical infection. Alternatively, infection can be caused by epidural injections or catheter placement or through hematogenous seeding. Risk factors for epidural abscess (besides having recently undergone spinal surgery or another procedure) are those that predispose to infection in general, including diabetes mellitus, intravenous drug use, alcoholism, and immunocompromised states. Staphylococcus aureus is the most common pathogen, followed by Streptococcus species and Staphylococcus epidermidis. More rare pathogens may be common in at-risk populations, such as the association of Pseudomonas with intravenous drug use. Untreated epidural abscesses will result in progressive neurologic deficits, sepsis, and possibly death.. Nonoperative, medical management may be considered for lumbar epidural abscesses in patients who are neurologically intact. However, extremely close follow-up is necessary to identify progression of disease and/or signs of sepsis. Cervical and thoracic epidural abscesses should be managed surgically on diagnosis because of the high incidence of permanent neurologic deficit and death. The standard treatment is decompression, with the approach guided by abscess location, closure over drains, and antibiotic therapy. Instrumented fusion should be utilized when osteomyelitis presents a risk of spinal instability. The use of autograft should be considered, as it may carry a lower risk of becoming a nidus for continued infection compared with allograft, metallic implants, or bone substitutes. As with epidural hematoma, decompression should be considered emergent when symptoms are severe or the patient demonstrates progressive neurologic decline. Fig. 73.4 T1 MRI images after injection of gadolinium demonstrate a multilevel epidural collection compressing the cauda equina, with involvement of the L5 and S1 vertebral bodies and the L5–S1 disk. Cultures confirmed infection. (A) Axial (L5–S1). (B) Sagittal.

Spine Emergencies

![]() Cauda Equina Syndrome (CES)

Cauda Equina Syndrome (CES)

![]() Epidural Hematoma

Epidural Hematoma

![]() Epidural Abscess

Epidural Abscess

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree