CHAPTER 62 Spinal Stenosis

Pathophysiology, Clinical Diagnosis, and Differential Diagnosis

Spinal stenosis is one of the most common conditions in the elderly. It is defined as a narrowing of the spinal canal. The term stenosis is derived from the Greek word for narrow, which is “stenos.” The first description of this condition is attributed to Antoine Portal in 1803. Verbiest1–10 is credited with coining the term spinal stenosis and the associated narrowing of the spinal canal as its potential cause. Kirkaldy-Willis11–15 subsequently described the degenerative cascade in the lumbar spine as the cause for the altered anatomy and pathophysiology in spinal stenosis.

The term spinal stenosis refers to an anatomic diagnosis that increases with age and can occur in asymptomatic individuals.16,17 The exact reason for why some with this condition have debilitating symptoms while others have no symptoms is not well understood. These differences in presentation may be related to the different abilities of individuals to compensate for the anatomic changes that have occurred. When symptoms do present, they usually occur on the basis of the location of neural compression. Patients with central canal stenosis typically present with neurogenic claudication, whereas those with lateral recess and foraminal stenosis present with radicular pain. Patients with significant symptoms that do not respond to conservative treatment often elect surgical treatment. In fact, in adults older than 65, spinal stenosis is the most common reason to undergo lumbar spine surgery.18,19

Anatomy

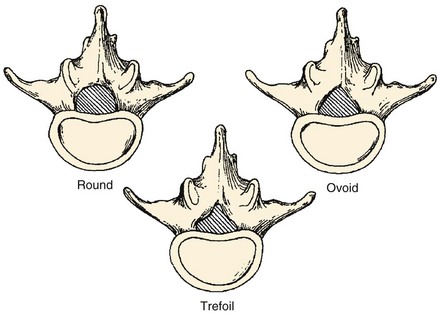

In order to understand how spinal stenosis causes symptoms, we must first have a good understanding of the normal anatomy of the lumbar spine. The spinal canal’s anterior border is formed by the vertebral body, the disc, and the posterior longitudinal ligament. The lateral border is formed by the pedicles, the lateral ligamentum flavum, and the neural foramen. The posterior border is formed by the facet joints, lamina, and ligamentum flavum. The shape of the spinal canal may be circular, oval, or trefoil (Fig. 62–1). The circular and oval canal shapes provide the most space for the neural elements centrally and in the lateral recess. The trefoil canal has the smallest cross-sectional area.20 It is present in 15% of the individuals and predisposes these individuals to lateral recess stenosis.

FIGURE 62–1 The three typical shapes of the spinal canal: Trefoil canals have the smallest cross-sectional area.

(From Hilibrand AS, Rand N: Degenerative lumbar stenosis: Diagnosis and management. J Am Assoc Orthop Surg 7:239-248, 1999.)

Disc

The Kirkaldy-Willis21 theory explains how these changes progress over time. This theory is based on viewing the spine as a tripod with the disc and the two facet joints making up the three legs. This analogy makes it easier to understand how alteration in one joint can alter the others. The initial stage in the degenerative cascade is circumferential tearing of the annulus, which progresses to radial tears. This, along with the biochemical changes in the disc described previously, leads to further degeneration of the disc and disc height loss. Altered disc structure and disc height loss lead to bulging of the disc and the posterior longitudinal ligament. This causes narrowing of the spinal canal and potential neural impingement. The lost disc height also leads to buckling of the ligamentum flavum and settling of the facet joints. The facet joints subsequently deteriorate and form osteophytes, which further narrows the spinal canal. The altered structure, motion, and biomechanics then lead to additional disc deterioration, which propagates the cycle of degeneration.

Intervertebral Foramen

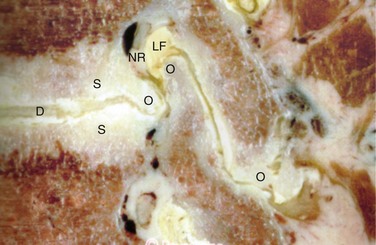

The anterior boundary of the intervertebral foramen is made up of the posterior wall of the vertebral body and the disc. The posterior boundary is made up of the lateral aspect of the facet joint and the ligamentum flavum. Superior and inferior boundaries are formed by the pedicles of the vertebral bodies corresponding to that segment. The foramen is typically larger than the ganglion and the nerve that it contains. The additional space is occupied by fat and loose areolar tissue that can accommodate for motion. With degeneration, hypertrophy of the facets can cause posterior compression of the neural elements (Fig. 62–2). Anterior compression of the neural elements usually arises from endplate osteophytes or foraminal disc herniations. Decrease in disc height with degeneration can cause a decrease in the foraminal height and neural compression. This type of vertical or up-down foraminal stenosis is important to recognize because a posterior decompression alone may not significantly improve the vertical compression and may result in persistent symptoms after surgery.

Cauda Equina

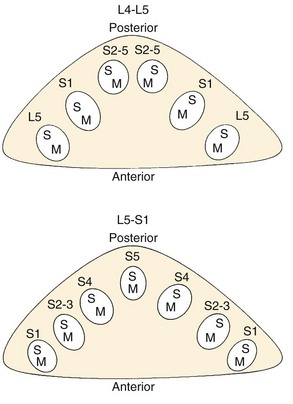

The thecal sac lies in the spinal canal and gives rise to nerve roots at each segment. The nerve root initially courses along the medial aspect of the pedicle and then progresses laterally, inferior to the pedicle in the neural foramen. The nerve roots within the cauda equina are arranged in a predictable pattern within the thecal sac (Fig. 62–3). Cross section of the thecal sac demonstrates the most caudal roots to be present in a central and posterior position. The more cephalad roots are located sequentially more lateral and anterior. At each level, the motor fibers of a root are anterior and medial to the larger sensory component. Dorsal root ganglia exist at every level and can be intraspinal or intraforaminal. A variety of clinical presentations arise on the basis of the anatomic location of neural compression.

Classification

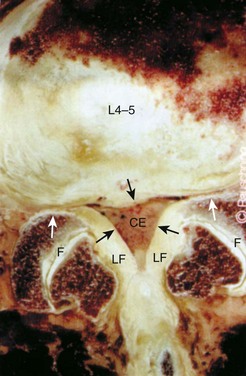

Stenosis can be anatomically classified as central, lateral recess, and foraminal on the basis of the location of neural compression. With aging, central canal stenosis occurs as degenerative changes progress. As the axial height of the disc and facet joints decreases, the disc bulges into the spinal canal. The central canal is further narrowed by posterior impingement from enlarged facets and the hypertrophied ligamentum flavum (Fig. 62–4). Hypertrophy of the soft tissues is responsible for 40% of spinal stenosis.22 With extension, the hypertrophied ligamentum buckles centrally into the canal and worsens the central stenosis. This explains why patients with stenosis typically report worsening of their symptoms in extension.

Lateral recess stenosis typically results from posterior disc protrusion in combination with some superior articular facet hypertrophy. Lateral recess stenosis can present with lumbar radiculopathy, and incidence of lateral recess stenosis ranges from 8% to 11%.23–25 These patients present with pain or neurologic symptoms in a dermatomal distribution on the basis of the nerve that is compressed in the lateral recess.

Foraminal stenosis causes compression of the exiting nerve root and ganglion and also leads to lumbar radiculopathy. Foraminal stenosis occurs most commonly in the lower lumbar spine with the fifth lumbar nerve root being the most commonly involved. Foraminal stenosis can occur from loss of disc height, vertebral endplate osteophytes, facet osteophytes, spondylolisthesis, and disc herniations. Like central canal stenosis, foraminal stenosis is worse in extension and thus exacerbating and alleviating factors for symptoms from foraminal compression are similar to those from central canal stenosis.26

Spinal stenosis can also be classified on the basis of the etiology, which can be congenital, acquired, or both. Congenital stenosis is present as a normal variant in the population and is part of certain conditions such as dwarfism. In these conditions, patients have short pedicles that are closer together than the normal lumbar spine. In congenital stenosis, few degenerative changes are sufficient to cause neural compression and symptoms. As one would expect, congenital stenosis becomes symptomatic much earlier in life and patients usually become symptomatic in the fourth decade. Acquired stenosis can be caused by trauma, neoplasms, and infection, along with other causes listed in Box 62–1.

Deformity and Instability

The static changes that we discussed thus far can be worsened by dynamic factors such as segmental instability. Instability typically arises from degenerative changes and can be in the form of translational or rotational abnormality. Translational abnormality is found most commonly in women as a degenerative anterolisthesis of L4 on L5.27 The attachment of the iliolumbar ligaments to the L5 level may act as a restraining force and cause more relative motion at L4-5. The more sagittally oriented facet joints between the fourth and fifth lumbar vertebrae can be an additional predisposing factor for instability at this level.28 Because the lamina and the spinous process typically project inferior to the vertebral body, the amount of room available between the inferior aspect of the L4 lamina and the posterior superior aspect of L5 is substantially decreased. This anterior translation of the L4 posterior elements, along with hypertrophy of the facets and the ligamentum flavum, leads to central and lateral recess stenosis. Foraminal stenosis can also occur in this setting with collapse of the disc space, disc herniation, endplate osteophytes, or facet hypertrophy. With scoliosis, lateral subluxation and rotational instability can cause altered biomechanics that leads to degeneration. The altered anatomy can also be a cause of narrowing of the central canal, lateral recess, and foraminal regions. Degenerative changes superimposed on abnormal anatomy lead to stenosis in these patients.

Pathophysiology

The term spinal stenosis describes the anatomic narrowing of the spinal canal. How does spinal stenosis result in pain and altered neurologic function? A number of cadaver and animal studies have attempted to elucidate the mechanism of these symptoms. Schonstorm evaluated the changes in nerve pressure that occur as the spinal canal narrows.29 In his human cadaver study, the thecal sac constriction of 45% or more led to an increased pressure in the nerve roots. As the degree of compression increased, the pressure in the nerve roots increased. Delamarter and colleagues30 also demonstrated the importance of the magnitude of thecal sac compression in alteration of neural function. They noted no alteration in neurologic function when the animal’s cauda equina was constricted by 25%, whereas more than 50% compression led to motor or sensory deficits. Pedowitz and colleagues31 demonstrated that the duration of compression was also an important factor in neural dysfunction.

Rydevik and colleagues32–37 demonstrated another effect of compression of the thecal sac. They noted that once pressure of more than 50 mm Hg was achieved, capillary restriction and electrophysiologic alteration occurred in the nerve roots. Even at pressures as low as 5 to 10 mm Hg, venous congestion of the intraneural microcirculation occurred. Solute transport decreased 45% across nerve root segments with the low pressure of 10 mm Hg. This suggests that low-grade sustained compression of the nerve roots could lead to vascular impairment and potential detrimental changes in the function of the nerve roots. In addition to neural compression and altered nutrition, inflammatory chemical mediators have also been shown to be a cause of pain.38–43

Natural History

Patients with congenital stenosis typically become symptomatic earlier in life. Due to congenital narrowing of the canal in these patients, significant stenosis is present at multiple levels even with little degenerative change.44 Patients with degenerative stenosis present later in life during their 60s and have far more advanced degeneration in their spine. Females are more commonly affected with stenosis and the L4-5 level is the most common segment involved.45

Multiple studies have looked at the short-term and long-term results of nonoperative treatment of patients with lumbar stenosis.46–53 These studies show that a significant number of patients respond favorably to nonoperative treatment. Some patients, however, do not improve and some even worsen. Johnsson and colleagues reviewed the results of 32 patients who declined to have surgery at a 4-year follow-up period.54 They noted that 70% of patients were unchanged, while 15% were the same and 15% worsened.

Recently, prospective studies have reported short-term and long-term results of nonoperative and operative treatment. The Maine Lumbar Spine prospective observational study reported 8- to 10-year follow-up results on 97 patients.55 They noted that a large number of patients (39%) that had initially elected nonsurgical treatment subsequently elected to undergo surgery. Of the patients who continued nonoperative treatment, most had stable symptoms. Miyamoto and colleagues reported prospective results of nonsurgical treatment in 120 patients.56 Sixteen percent of the patients required surgical treatment during the follow-up period of 5 years. Of the nonsurgically treated patients, 53% of patients reported no hindrance during the activities of daily living. No sudden neurologic deterioration was reported. Roughly 23% of patients had worsened but did not elect to undergo surgical intervention.

The Finnish Lumbar Spinal Research Group reported the results of a randomized controlled trial in 2007.57 They randomized 94 patients with mild to moderate stenosis into either the surgical group or nonoperative group. At the 2-year follow-up, patients noted improvement of symptoms in both groups; however, the outcome of patients undergoing surgical treatment was significantly better. The most recent prospective study to evaluate patients with lumbar stenosis is the SPORT study.58 This study reported prospective outcomes of 634 patients at 2-year follow-up. Patients undergoing surgical treatment had better outcomes than those who underwent nonsurgical treatment. Patients in the nonsurgical treatment group showed small improvements in most outcome measures. It should be noted that no disastrous neurologic deterioration was noted with nonoperative treatment.

The recently published North American Spine Society evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of lumbar stenosis provide some tangible conclusions from these studies.59 They state that in one third to one half of patients with mild to moderate stenosis, the natural history is favorable. Unfortunately, predicting which patients with stenosis will worsen over time is impossible. In some studies symptomatic patients with severe stenosis did poorly over time, but overall there is not sufficient evidence to draw any conclusions. What is known is that rapid or catastrophic deterioration is rare in patients with spinal stenosis. Knowing this can be helpful in guiding treatment and evaluating these patients. When a patient with spinal stenosis has rapidly worsening neurologic status, other causes of neurologic dysfunction should be investigated.

Clinical Presentation

Patients with lumbar spinal stenosis most commonly present with leg pain.22 This leg pain presents as either neurogenic claudication or radicular leg pain. Patients with neurogenic claudication report a feeling of pain, heaviness, numbness, cramping, burning, or weakness. The symptoms typically start from the back or the buttocks and bilaterally radiate down below the knees. One lower extremity may be worse than the other; however, both legs are typically involved. Symptoms usually do not follow a dermatomal pattern and are usually related to activities. These abnormal sensations are typically worse with extension of the lumbar spine during walking or standing for a prolonged time. Some report worsening weakness if they keep walking. They may note ankle dorsiflexion weakness that is typically described as feet slapping or even falling as they attempt to keep walking. Walking downhill is more challenging for these patients as the lumbar spine is extended while going downhill. Most describe a set distance they can walk before the symptoms become disabling. As the stenosis worsens, this distance typically decreases, further disrupting the daily life and function of these patients. Relief of symptoms typically comes from flexing the lumbar spine by leaning forward, sitting, or lying down. As discussed earlier, the degree of stenosis decreases as the lumbar spine is flexed and patients naturally learn to position themselves in a posture that minimizes discomfort and maximizes function. Keeping this in mind, it is easy to understand why these patients typically lean forward on a grocery cart and have an easier time riding a bike, walking uphill, or driving while sitting in a car.

Low back pain is also a common complaint in patients with stenosis. Although most patients note the radiation of this pain into their legs, some present without leg pain or note radiation of the pain only into their buttocks. Exacerbating and alleviating factors for claudicatory low back pain are similar to those for the leg pain. Spondylotic change with or without spondylolisthesis is a common finding in this patient population and often the cause for low back pain. Patients with symptoms in both the low back and leg have a greater disability than those who have symptoms only in one location.60

Severe neurologic symptoms such as bowel and bladder incontinence or profound weakness are uncommon in patients with stenosis. Urinary dysfunction is a common complaint in this elderly population and can be present in 50% to 80% of patients.61,62 Because various causes of urinary dysfunction such as preexisting stress incontinence, urinary tract infections, and prostatic hypertrophy are common in this population, a careful history can help exclude these common causes. The factors more commonly noted in patients with neurogenic bladder dysfunction are perianal sensory disturbance, longer duration of symptoms, and higher mean residual volumes on urodynamic studies.63

In addition to obtaining a history specific to the patient’s pain and neurologic symptoms, it is important to obtain a comprehensive medical history. A patient’s report of preexisting peripheral arterial occlusive disease, hip arthritis, multiple sclerosis, or neuropathy would substantially alter what symptoms are attributed to the stenosis. Similarly, obtaining an overall picture of the medical comorbidities and physiologic condition will also shed light on the ability of the patient to safely undergo any invasive procedures. Knowing the patient’s other medical conditions can also help identify patients who may be at risk for inferior outcomes. Cardiovascular comorbidities, depression, and disorders influencing walking ability have all been noted to be preoperative predictors of poor postoperative outcomes.64