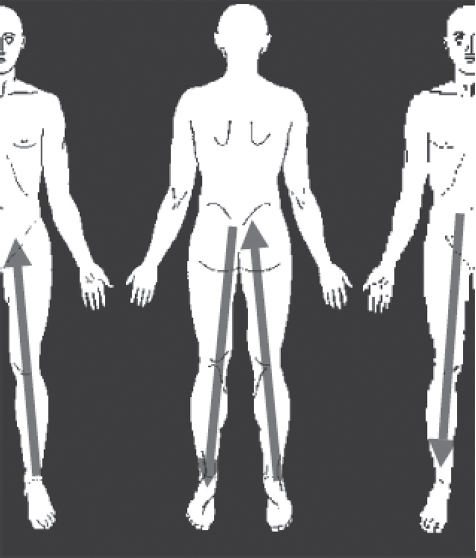

69 Spinal cord stimulation (SCS) is a method of treating neuropathic pain involving implantation of electrodes, which deliver electrical current onto several spinal cord structures, including the dorsal columns. This electrical stimulation activates afferent pathways that inhibit pain perception. While SCS has been commonly used to treat failed back surgery syndrome (see Chapter 68), it also has applications for several other types of neuropathic pain affecting the extremities, such as complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) and brachial plexitis or neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome. This chapter focuses specifically on the use of SCS to treat pain syndromes involving the extremities. For more details on the mechanisms of function of SCS and techniques of treatment, refer to Chapter 68. Patients with failed back surgery syndrome can experience persistent or multi-distribution radicular pain in the extremities originating from the spine, indicating treatment with SCS. Radicular pain is characterized by a distribution of pain that radiates along somatosensory dermatomes. This type of pain may be precipitated by inflammation or irritation of the nerve root, known as radiculitis; however, radicular pain may be caused by other mechanisms as well, such as fibrosis. There are several pain syndromes that originate in the spinal cord but primarily affect the extremities. CRPS, previously known as reflex sympathetic dystrophy (RSD), is a pain syndrome that occurs with unknown etiology (Type I) or secondary to injury (Type II). It is characterized by progressive severe pain, swelling, and skin color changes occurring in the hands, feet, knees, or elbows. Another pain syndrome of the extremities is brachial plexitis, which is defined as a pain affecting the upper extremities, the shoulder, the trapezius, the axilla, and/or the upper chest wall. This may result from viral influence, anatomical deformity, or even traumatic injury. Potential candidates for SCS are patients with severe neuropathic pain syndromes who have failed to achieve successful pain reduction through more conservative methods, do not have a serious untreated drug habituation, and are free of confounding comorbidities that may indicate nociceptive or mechanically correctable origins of pain. Persistent radicular pain following one or more failed lumbosacral surgeries can present with a variety of described pain experiences ranging from sharp, dull, piercing, and throbbing, to burning. In some cases, the pain can change or be relieved with mechanically altered body position, such as lying down versus standing or bending forward. These may sometime be amenable to spinal surgery. The dermatomal distribution of pain is indicative of the spinal cord or nerve level involved; however, individual variations exist, and pain distribution does not always fit expected dermatomal patterns. When paresthesia accompanies pain, the distribution of paresthesia is more characteristic, and localization of the affected spinal cord level is more precise than with pain alone. Recently, Bennet et al. reported on and validated the use of a neuropathic pain scale. On this scale, there are a total of 24 points, and greater than 12 points is typically suggestive of neuropathic pain. Interestingly, the most significant descriptors of pain suggestive of neuropathic pain included the presence of abnormal sensations in the pain region, color changes in the pain region, and different feeling in the pain region with finger rubbing when compared with nonpainful regions. Other characteristics observed included abnormal sensitivity, pressing-associated pain, and bursting pain, with burning being the least significant. This scale is useful in giving an overall impression that a component of the limb pain may be neuropathic in origin. Patients with CRPS typically present with burning pain and allodynia that is most prevalent in a limb but can affect any part of the body. The patient’s description of the pain is often the most helpful in the diagnosis of this disease. In Type II CRPS, the onset of pain most often occurs ~ 24 hours from the injury; however, if the injury initially causes anesthesia, the pain symptoms may have a much later onset. The most commonly involved nerves in CRPS are the median, ulnar, and sciatic nerves, but specific nerve involvement often cannot be determined. Brachial neuritis typically presents with acute onset of intense pain and sometimes muscle weakness, which can occur simultaneously with the onset of pain or after a variable period. This pain syndrome is characterized as a constant sharp, stabbing, throbbing, or aching that can last for several weeks. Finally, it should be recognized that many patients may have mixed pain etiologies. Patients might easily have both a nociceptive component as well as a neuropathic component of pain. For example, a patient with a traumatic herniated lumbar disk may have both a simple radiculopathy, resulting in leg/limb pain from mechanical injury to the nerve root, and chemical irritation from the nucleus pulposus. However, identification of multidermatomal pain distribution with altered sensory patterns and hyperpathia would suggest an overlying neuropathic injury. This patient might require a planned, staged spinal intervention and neurostimulation intervention if other less invasive and conservative efforts fail. Upfront discussion with the patient on this treatment plan is, of course, very helpful. The most important tests of the physical exam to help diagnose the cause of lumbosacral radicular pain is the straight leg-raising test, or Lasègue’s test, and the crossed straight leg-raising test. A positive test result, or Lasègue sign, is radicular pain elicited at an angle of less than 60 degrees when the leg is raised from the exam table. Although never proven, Lasègue sign has been considered an indication of nerve compression and may indicate that a patient is not a good candidate for SCS. Another strong indication that a patient is not a good candidate for SCS would be a positive test result when performing the crossed straight leg-raising test, which occurs when the contralateral leg is raised and pain is elicited on the ipsilateral side. In addition, some neurological signs, such as decreased patellar and Achilles tendon reflexes, can indicate a physical etiology at the nerve root. Other indications for SCS are a Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Pain Symptoms and Signs score greater than 12, demonstrating pain of neuropathic origin, and opiate and neuropathic pain medication usage. Examining a patient with CRPS is often difficult because of the pain experience of the patient—often the patient will not allow touch to the affected limb. Additional physical findings consist of vascular changes that can alter the appearance of affected areas of the body. The results of these changes include vasodilation or vasoconstriction, anhidrosis or hyperhidrosis, dry and scaly skin, stiff joints, tapering fingers, ridges in fingernails, and long and coarse hair or alopecia. Finally, patients with brachial plexitis present with weakness or paralysis of the shoulder girdle muscles and mixed loss of sensory modalities in the affected arm. Some of these patients will experience extreme tenderness to palpation in the supraclavicular region or in the subclavicular region. For any of the pain syndromes just described, the appropriate imaging studies, especially computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), should be conducted to rule out physical etiologies of pain that can be treated with more conventional methods or surgical procedures. In particular, patients with suspected persistent radicular pain following previous lumbosacral procedures and brachial plexitis should have an MRI at the suspected level of spinal cord involvement. These imaging studies should be conducted after the pain is expected to resolve on its own. For radicular pain associated with failed back surgery, the pain sometimes resolves after 6 to 12 weeks. Idiopathic brachial plexitis can begin to resolve ~ 4 weeks after the onset of pain. If patients with these pain syndromes have not experienced a decrease in pain during these time periods, imaging studies can help identify nociceptive causes. Diagnosis of radicular pain can also be aided by performing a diagnostic nerve root block, which is particularly helpful in determining the level of spinal cord involvement; however, the specificity and sensitivity of this test are undetermined. Some tests that may be useful in confirming diagnosis of CRPS include thermography, three-phase bone scan, radiographic examination for osteoporosis, response to sympathetic block, and autonomic tests, such as sweat output and skin temperature at rest and quantitative sudomotor axon reflex test. There are a few unique issues to also consider prior to implantation of a permanent neurostimulator system. The implantation of a neurostimulator does preclude future MRI scans. Therefore, the physician and patient may consider MRI of other body regions prior to implantation and should try to also assess what the necessity of MRI may be in the future. For example, if a patient has a brain tumor and is being monitored for recurrence, that patient would need to be evaluated with CT scans instead of MRI. If this is not feasible, then a neurostimulation system may be contraindicated. Additionally, many patients may elect to have a paddle electrode inserted as their permanent implant system. Given the size of a paddle lead and considerations of having adequate space for insertion in the epidural space in the cervical or thoracic regions, it may often be desirable to obtain MRI of either the cervical or thoracic spine, prior to permanent implantation to assess for relative stenosis and to ensure that there is adequate room for paddle placement. In treating extremity pain with SCS, percutaneous and paddle electrodes can be used. As mentioned in Chapter 68, percutaneous electrodes require less invasive procedures for implantation; however, they are perceived to have a greater tendency to migrate from the desired site and break. Other studies have indicated that this may not be true. The rate of percutaneous electrode migration has been demonstrated to be slightly less than the rate of paddle electrode migration. In addition, the rate of percutaneous electrode breakage has been demonstrated to be almost half the rate of breakage of paddle electrodes. Conversely, paddle electrodes require surgery for implantation and are believed to deliver current to the dorsal columns more efficiently than percutaneous electrodes. Radiofrequency generators and implantable pulse generators can be used to deliver current through the electrodes to the dorsal columns. There are four different regions where surgeons can achieve stimulation of the large, myelinated afferents resulting in ipsilateral tingling paresthesia: the dorsal root, the dorsal root entry zone (DREZ), the dorsal horn, and the dorsal columns. It is important to note the difference in activation of the dorsal root, the DREZ, and the dorsal horn from activation of the dorsal columns because activation of the dorsal root aspects of these afferents results in radicular paresthesia of the dermatome at the level of the electrode, while activation of the dorsal columns cause paresthesia of areas of the body caudal to the level of the electrode. Furthermore, It can be extremely difficult to differentiate between stimulation occurring at the dorsal root, DREZ, or dorsal horn. Dorsal root stimulation occurs with laterally placed electrodes, while stimulation of the DREZ and dorsal horn occurs with electrodes placed closer to the midline. Stimulation of the DREZ and dorsal horn causes segmentary paresthesia that is subsequently followed by rapid activation of the dorsal columns with a small voltage increment. Minute changes in the mediolateral positioning of electrodes have been demonstrated to cause movement of paresthesia patterns in a two-dimensional “W” pattern (Fig. 69.1). Fig. 69.1 Depiction of the two-dimensional “W” pattern of paresthesia observed with variations in mediolateral positioning of SCS electrodes on the dorsal root, DREZ, dorsal horn, and dorsal columns. (From Oakley JC, Espinosa F, Bothe H et al. Transverse Tripolar Spinal Cord Stimulation: Results of an International Multicenter Study. Neuromodulation. 2006;9(3):192–203. Reprinted with permission.)

Spinal Cord Stimulators for Extremity Pain

![]() Classification

Classification

![]() Workup

Workup

History

Physical Examination

Imaging Studies

Special Diagnostic Considerations

![]() Treatment

Treatment

Equipment

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree