Chapter 55 Socioeconomic and Disability Aspects

Like many other chronic illnesses, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) can have a major impact on physical and social functioning and work ability.1 The costs of care and the economic consequences of illness can be substantial. Fatigue, pain, cardiopulmonary symptoms, cognitive impairment, and neurologic deficits can cause difficulty performing activities of daily living and work tasks.2 These symptoms and signs, along with the psychological adjustment to illness, can affect how patients manage activities and function at home, school, and work. This chapter examines the impact of SLE on physical and social functioning, schooling, family life, and work ability, as well as the costs of SLE.

Two considerations are important in the evaluation of studies of these outcomes in patients with SLE. First, the source of the patient sample should be considered. Most studies have been performed on samples of patients treated at specialty centers, often ones focused on the treatment of SLE. These samples are convenient but are not representative of all patients with SLE and include higher proportions of patients with more severe illness.3 Findings are therefore skewed to a more pessimistic appraisal of functioning than is truly the case. To obtain a true assessment of functional status and of the social and economic consequences of SLE, population-based samples should be studied. Population-based studies use all patients in a given locality as the sample, thereby avoiding biases due to selective referral and ensuring that the study includes, in correct proportions, patients across the entire range of severity of illness. Population-based studies are difficult to perform but are valuable sources of information. Community-based studies, which enroll participants from multiple different sources and are not exclusively from clinics, are likely more representative than clinic-based samples. Second, mean results should not be generalized to all patients. All measures have a distribution, and the distribution of results among patients with SLE often overlaps that of healthy individuals. Many patients with SLE have normal functioning and work ability, and impairment should not be viewed as expected or inevitable.

Physical and Mental Functioning

Physical functioning refers to an individual’s ability to perform basic activities of daily living, such as dressing, bathing, and moving about, and instrumental activities of daily living, such as housework, shopping, and preparing meals. Function is most often measured using patient-reported questionnaires, based on the belief that patients are the most accurate observers of their own abilities. Commonly used measures of physical function, such as the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) Disability Index and the Medical Outcomes Study short form 36 (SF-36) physical function subscale, include both basic and instrumental activities and integrate them into a single score.4,5 The physical function subscale of the SF-36 also contributes to the “Physical Component Summary,” along with ratings of pain (a symptom rather than a rating of function), general health, and limitations in performing a societal role (e.g., work, housework, schoolwork) as a result of physical health problems. Mental functioning refers to an individual’s ability to enjoy life and participate in social interactions. The mental component summary (MCS) of the SF-36 includes ratings of mood, social functioning, fatigue (a symptom), and limitations in performing an individual’s societal role because of psychological concerns.5 Although the concept of health-related quality of life includes functioning, it also includes symptoms, perceptions, and satisfaction with health.1

Physical Functioning

Functional limitations among patients with SLE as measured by the HAQ have generally been reported as mild.6 In eight cross-sectional studies, all of the patients at referral centers and with samples ranging from 82 to 202 patients, the mean HAQ score ranged from 0.36 to 1.3 (median 0.64) on a 0 to 3 scale, with higher scores indicating greater impairment.7–14 The variability in scores among patients was high in all studies. Twenty-five percent of patients had an HAQ score of 0.7,10 The most problematic task was performing errands and chores.8 Scores were higher among older patients, possibly as a result of co-morbid conditions, and among obese patients.11,12,15 Scores were also higher among patients with active SLE or permanent organ damage and were correlated with self-reported pain.7–1012 Higher scores have also been reported among those with fibromyalgia, depression, and life stresses, indicating associations between mental functioning and perceptions of physical impairments.9,11,13,16 Studies have not generally reported associations between HAQ scores and the duration of SLE, suggesting that functional limitations are often not progressive.17

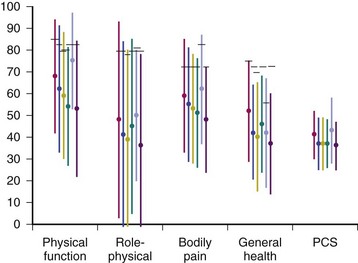

The SF-36 has been used much more extensively than the HAQ to measure physical functioning in SLE, because functional limitations have been more commonly detected using this measure. Many studies include relatively small samples from single-referral centers, but four studies are notable for their large size. The Tri-Nation study included 708 unselected patients (mean age, 40 years; mean duration of SLE, 10 years) from six referral centers, two each in Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States.18 The LUMINA (LUpus in MInorities, NAture versus nurture) study reported data on 346 patients at four referral centers in the United States who enrolled within 5 years of the onset of SLE.19 Tam and colleagues20 studied 291 unselected patients (mean age, 42 years; mean duration of SLE, 9.7 years) at a single tertiary center in Hong Kong. Wolfe and colleagues21 surveyed 1316 patients (mean age, 50 years) in a U.S. nationwide observational study. Results of these studies are generally consistent (Figure 55-1). Mean results for all four physical component subscales—physical functioning, role-physical, bodily pain, and general health—were significantly lower than those of population controls, but values for the physical functioning, role-physical, and bodily pain scales were within 1 standard deviation of the scores in the general population. Scores were lowest on the role-physical subscale, which measures limitations in work or housework as a result of physical problems, and the general health subscale. These scores diverged most from those of the general population, indicating that these subscales are most affected by SLE. The physical component summary (PCS) scores ranged from 37 to 43. These values were slightly more than 1 standard deviation lower than the standardized population score of 50, indicating that SLE has a notable impact on physical health for the typical patient.

FIGURE 55-1 Scores on the physical health short form 36 (SF-36) subscales and the physical component summary (PCS) by study. Values are means; error bars are standard deviations. Short horizontal bars represent control sample or country-specific population means. Population mean of the PCS is 50 for all studies. Tri-Nation Canada, red; Tri-Nation United States, blue; Tri-Nation United Kingdom, yellow18; LUMINA, green19; Tam and associates, gray20; Wolfe and associates, purple.21

Advancing age, lower socioeconomic status, more permanent organ damage, and more co-morbid medical conditions were associated with poorer physical health.20,21 In the LUMINA study, the presence of fibromyalgia was the most important correlate of the PCS score.19 Lower self-efficacy, less knowledge about SLE, and less social support have also been associated with poorer physical health as measured by the SF-36.22

SF-36 physical function scores have been found to be generally stable over periods up to 8 years in patients with SLE.19,23–25 Worsening over time was more likely in older patients,19,23,25 those with fibromyalgia,19,24 Caucasians,24 and patients with a recent flare in symptoms.25

Mental Functioning

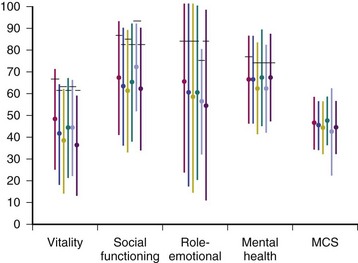

Findings on mental functioning as measured by the SF-36 are remarkably consistent among these four large studies (Figure 55-2).18–21 Although scores were uniformly lowest on the vitality (fatigue) subscale, scores on the vitality, social functioning, and role-emotional subscales were equally divergent from those of the general population. The MCS scores ranged from 42 to 47, only slightly lower than the standardized population score of 50. These findings indicate that patients with SLE have less severe impairments in mental functioning relative to the general population than they do in physical functioning. However, one third of patients report being unable to participate in at least one valued life activity, primarily discretionary leisure and social activities.26

FIGURE 55-2 Scores on the mental health short form 36 (SF-36) subscales and the mental component summary (MCS) by study. Values are means; error bars are standard deviations. Short horizontal bars represent control sample or country-specific population means. Population mean of the MCS is 50 for all studies. Tri-Nation Canada, red; Tri-Nation United States, blue; Tri-Nation United Kingdom, yellow18; LUMINA, green19; Tam and associates, gray20; Wolfe and associates, purple.21

Lower socioeconomic status, less social support, and the presence of fibromyalgia have been associated with poorer mental functioning,19,22 as have younger age and more co-morbidities.21 In longitudinal studies, mental functioning has generally been found to be stable over time.19,23–25 Predictors of change in mental functioning have been more difficult to identify than predictors of change in physical functioning, but patients of lower socioeconomic status or African-American ethnicity and those with fibromyalgia may be more likely to experience worsening.19

Interventions

Educational and cognitive-behavioral interventions have been tested as ways (other than medications) to improve functioning in patients with SLE. In a small short-term trial, patients receiving the Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Self-Help (SLESH) course, an educational intervention modeled after the Arthritis Self-Management Program, had modest improvements in depression and self-efficacy.27 A 6-month telephone counseling intervention focused on enhancing self-care improved physical function but not pain, fatigue, or affect.28 A stress management and cognitive restructuring intervention improved physical function but not mental functioning over 15 months in a small trial.29 In the largest study, an intervention designed to increase self-efficacy and social support improved fatigue and the MCS score of the SF-36 over 12 months, but not physical function.30 These results support the use of these interventions, but adoption has been limited because of the need for trained counselors.

Schooling and Family Life

SLE most often begins at ages when most people have completed their formal education. However, when SLE begins in childhood or adolescence, patients may experience major effects on schooling. In a cross-sectional study at two referral centers of 41 patients with SLE, ages 9 to 18 years, patients missed a median of 1 day of school per month, either for medical appointments or because of illness.31 Although some were satisfied with their school performance, two thirds reported difficulty concentrating, remembering, or keeping up with assignments. In studies using the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL) measures, school was the domain most affected among children with SLE, with scores much lower than in healthy children.31,32 The school domain asks about problems paying attention, remembering, and keeping up with work, as well as the number of days of school that were missed. Cognitive impairment and mood disorders can interfere with school performance, but the limited data available suggest that SLE does not generally limit educational attainment.33–35

The proportion of women with SLE who are married is similar to that in the general population, and most report that SLE had no effect on the relationship with their partner.35–37 However, concerns about the future course of illness and medication use may affect decisions regarding childbearing.38 Although women with SLE are as likely as women without SLE to have children, women with SLE are less likely to have several children, suggesting that decisions to limit family size are not uncommon.38,39

Employment and Work Disability

One of the central roles of adulthood is that of worker. Work provides not only income to purchase material goods, support leisure interests, and generate assets for late life and retirement but also social standing, self-esteem, and opportunities for social interaction. Three work-related outcomes are often examined in patients with chronic illnesses: (1) employment, (2) work disability, and (3) receipt of disability pensions. Employment is the most general and merely considers whether or not the patient is working for pay. Because many factors other than illness influence employment, such as the local job market or the desire for more schooling, and because employment is discretionary for some people, it is less specifically related to disease status than work disability. Work disability refers to the patient-reported inability to work as a result of illness. Estimates of work disability are most appropriately limited to those who were working before the onset of illness. Receipt of disability pensions represents work disability that is certified and compensated by governmental agencies or insurers. Although receipt of disability pensions often signifies a permanent inability to work, this measure underestimates the frequency of work disability, because many patients with SLE who are work disabled do not apply for or are denied disability certification.40–42 Patient-reported work disability is the work-related outcome that can most directly reflect the impact of medical treatment, because it is ascribed to illness, does not consider those who are electively out of the workforce, and is not influenced by selection factors as are disability pensions.

Employment

In cross-sectional studies of adults with a wide range of durations of SLE and mostly of patients treated at specialty rheumatology clinics, 41% to 55% of patients with SLE were employed.43–47 In the 1990s, patients with SLE in Germany were only 80% as likely to be employed as those in the general population.48 Earlier community-based studies reported no relative decrease in employment among patients with SLE.35,49 In an inception cohort in the United States, 26% of patients stopped working after 3 years of illness, a rate three times higher than that of controls, highlighting the impact of new and perhaps uncontrolled disease on work status.50 In another large U.S. cohort, employment at 5, 10, and 15 years of SLE duration was estimated at 85%, 64%, and 49%, respectively.51 Among employed patients with an average duration of SLE of 11 years, the risk of subsequent unemployment was similar to that in matched population controls, suggesting that the time of greatest risk of unemployment is early in the course of SLE. However, patients with SLE who are unemployed are 50% less likely than matched controls to regain employment.51

Unemployment is more common among older patients and those with longer durations of SLE and lower educational attainment.43–46,48,51 Clinical predictors are less clear, because most studies of risk factors have been cross-sectional. Clinical manifestations present at the time of the study may be different from those before the work loss, which may have occurred many years earlier. In two prospective studies, the risk of unemployment was strongly associated with both depression and cognitive impairment.46,51

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree