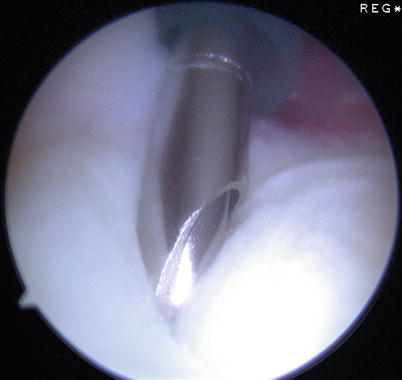

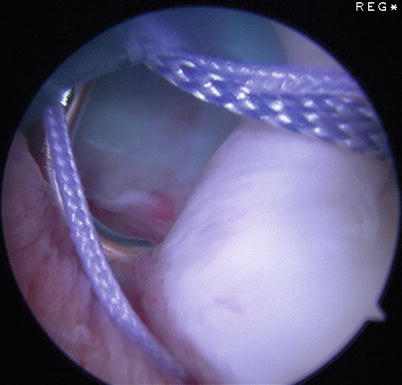

Fig. 17.1

Using a probe, the SLAP type II lesion was confirmed according to the existence of a complete detachment of the biceps anchor from the superior glenoid tubercle, besides certain fraying of the edge of the labrum

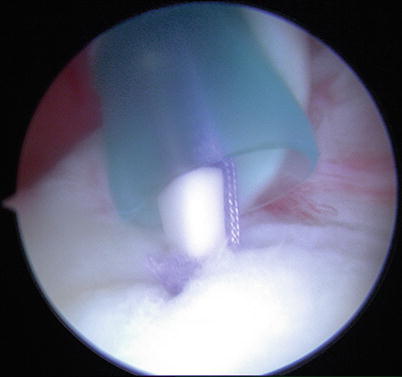

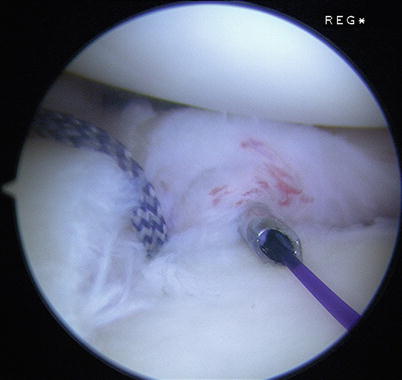

Fig. 17.2

A 4.5 mm shaver was used in order to regularize the edge of the superior labrum when necessary and debride to bleeding bone the superior part of the glenoid neck

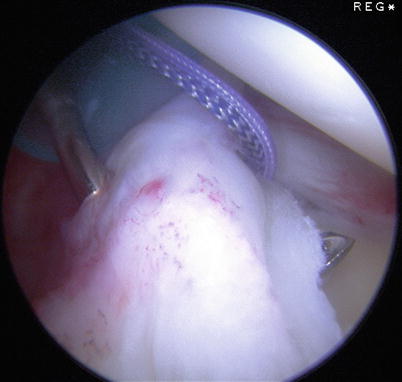

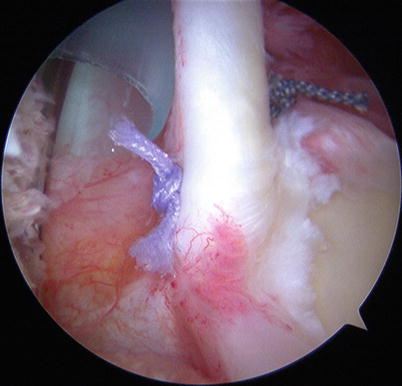

Fig. 17.3

Using the anterior portal, a bioabsorbable anchor loaded with two sutures (Lupine Depuy Mitek) was inserted into a predrilled hole in the glenoid rim just below the biceps anchor, 2–3 mm medial to the articular surface (12 o’clock position)

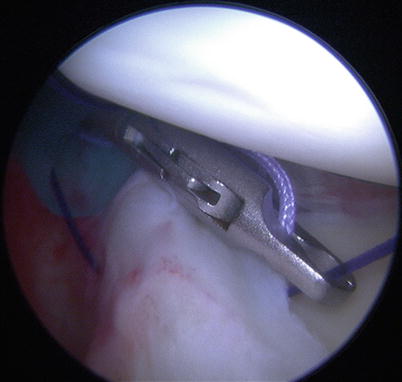

Fig. 17.4

With the help of a suture passer, a free non-resorbable monofilament suture is passed through the posteromedial aspect of the biceps anchor from superior and medial to inferior and lateral, emerging just under the posterior aspect of the superior labrum

Fig. 17.5

The intrarticular end of this monofilament suture is retrieved through the antero-superior portal in order to shuttle one of the limbs of the sutures in the anchor through the labrum

Fig. 17.6

The other limb is passed through the labrum adjacent to the biceps, a few millimeters anterior to the first one, thus creating a mattress stitch

Fig. 17.7

The horizontal matress suture should not cross over point “A” (anterior edge of LHB on the labrum)

Fig. 17.8

Using the same suture passer technique, one of the limbs of the second suture of the anchor is passed through the superior labrum at the level of the insertion of the MGHL and the SGHL, creating a simple stitch

Fig. 17.9

Finally, the biceps and labral stability is tested with a probe

We reported our above-described technique for isolated SLAP II lesion repair with a short-term follow-up [10]. Nine males (64.3 %) and five females aged 28.4 ± 6.6 years were included in this study. The mean follow-up was 12.7 ± 7.4 months (range, 5–24). The dominant arm was involved in 10 cases (71.4 %), while the right arm was involved in 78.6 % of the cases. Every single patient was assessed before and after surgery by the passive ROM and using the Constant score [12], the ASES score [33], the UCLA score, and the ROWE score. The O’Brien and the painful apprehension tests were used for clinical diagnosis [17]. All the patients underwent an arthro-MRI for imaging confirmation before surgery. For each enrolled patient, a standardized form reporting demographic data (age, sex), time of follow-up, dominant arm (right/left), affected shoulder, passive ROM, Constant score [12], ASES score, UCLA score, ROWE score, O’Brien test, the time of the surgery (time zero), and the time of follow-up (6 months and final follow-up) was completed. For the comparison of the means at different times, a Student t-test for paired samples was used. A multiple logistic regression model to evaluate a relationship with age, sex, and sport of the examined parameters was performed. The level of significance was set at p < 0.05.

Of the 14 patients operated with this technique from 2011 to 2012, all the patients had isolated SLAP II lesions. The number and proportion of patients with positive O’Brien sign was 12 (85.7 %) at time zero and 1 (7.1 %) at 6 months and at final follow-up (chi-square = 15.2; p < 0.0001) (Table 17.1). Means of Constant [12], ASES [33], ROWE, and SST scores and VAS (visual analog scale for pain evaluation) statistically improved from time zero to 6 months and from 6 months to final follow-up (Table 17.2). The number and proportion of patients who referred to practice sports was 12 (85.7 %) at time zero, 10 (71.4 %) at 6 months follow-up, and 10 (71.4 %) at final follow-up (chi-square = 0.6; n.s). Of the four patients who had participated in overhead agonistic athletics preoperatively (volleyball and tennis), all the four were able to return to their preinjury level. The mean value of passive abduction (ABD), external rotation with arm at side (ER1), and external rotation with 90° of abduction of the arm (ER2) did not differ in the three evaluations (n.s.). Anterior flexion of the arm (AF) and internal rotation of the arm (IR) were increased from 6 months to final follow-up (t = 2.9; p = 0.0065) (Table 17.3). The apprehension and relocation tests were positive in eight patients before surgery and negative in all the cases after surgery (chi-square = 13.3; p = 0.003). Clinical scores were better in male patients (t = 2.7 p = 0.028), if the dominant arm was involved (t = 3.4, p = 0.010) and in older patients (low significance) (t = 2.3 p = 0.046). Passive ROM was not reduced by surgery (Table 17.3). The main difference with a standard repair is that in the reported technique, a mattress stitch to reinsert the medial supratubercle origin of the biceps fibers, at the medial side of the biceps anchor, and a simple stitch anteriorly, through the superior labrum at the level of the insertion of the MGHL and the SGHL, are applied, thus stabilizing those ligaments. In the standard repair, two simple stitches are applied anteriorly and posteriorly to the biceps, and this can strangle the LHB and can create pain with loss of joint mobility [4]. In the reported technique, the anatomy is respected: the articular aspect of the superior labrum is loose and the medial side reinforced.

Table 17.1

Detailed list of the enrolled patients including sports, function, and symptoms before surgery

Enrolled patients | Elite throwing sport performed | Mean Constant score preop. ± SD | O’Brien sign | Apprehension and relocation test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

14 | 4 | 64.6 ± 13.9 | 12 | 8 |

Table 17.2

Means values and standard deviations with statistical analysis of Constant, ASES, ROWE Scores; VAS; and SST at time zero, 6 months’ follow-up, and at final follow-up

Scores | Time zero | Follow-up 6 months ± SD | Time zero versus 6 months | Final follow-up ± SD | 6 months versus 12 months |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Constant | 64.6 ± 13.9 | 80.7 ± 25.1 | t = 1.9 | 92.6 ± 11.8 | t = 6.5 |

p = 0.04 | p < 0.0001 | ||||

ASES | 76.9 ± 22.4 | 100.6 ± 7.5 | t = 3.8 | 108.3 ± 8.5 | t = 5.0 |

p = 0.001 | p = 0.001 | ||||

ROWE | 53.6 ± 20.6 | 88.6 ± 10.1 | t = 7.4 | 96.5 ± 7.2 | t = 7.8 |

p < 0.0001 | p < 0.0001 | ||||

VAS | 5.7 ± 3.4 | 2.1 ± 1.5 | t = 6.4 | 0.57 ± 0.93 | t = 5.7 |

p < 0.0001 | p < 0.0001 | ||||

SST | 6.9 ± 2.1 | 8.5 ± 0.6 | t = 2.5 | 9.1 ± 0.9 | t = 3.1 |

p = 0.013 | p = 0.0039 |

Table 17.3

Means values and standard deviations (SD) with statistical analysis of ABD, AF, ER1, ER2, and IR at time zero, 6 months’ follow-up, and at final follow-up

Time zero

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|

|---|