Fig. 22.1

MR – partial-thickness cuff tear on the articular side

Fig. 22.2

MR – partial-thickness cuff tear on the bursal side

Fig. 22.3

Arthroscopy – partial-thickness cuff tear on the articular side (Ellman grade 1)

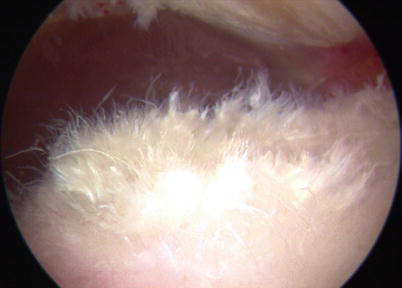

Fig. 22.4

Arthroscopy – partial-thickness cuff tear on the articular side (Ellman grade 3)

Fig. 22.5

Arthroscopy – partial-thickness cuff tear on the bursal side

22.4 Treatment Strategy

A complete diagnostic evaluation of the glenohumeral joint is necessary before choosing for a nonoperative or an operative treatment. In particular, in the overhead athletes, lesions of the superior labrum and of the capsulolabral structures should not be underestimated [20].

It’s also important to understand that the needed outcome of operative treatment is different between a professional and a recreational athlete: high-level athletes have a strong inferior prognosis to come back at the pre-injury level in opposite with middle-age amateur athletes, which normally are satisfied [21].

22.4.1 Nonoperative Management

Generic guidelines exist, but nonoperative treatment must be specific for each patient, considering the grade of his or her pathology and his or her individual sport-specific demands. This treatment is divided in four main phases [1]:

Phase 1: it consists in rest from sport and irritating activities, in association with anti-inflammatory strategies such as phonophoresis, iontophoresis, ice massage, or ice pack application. Passive or active-assisted range-of-motion exercises are started in pain-free ranges (in these range-of-motion exercises, collagen tissue tension stimulates collagen healing). Rotational exercise is performed at 45° scapular plane abduction (below the impingement zone) and then increased with the symptom improvement. Pain-free submaximal exercise can be started. Strengthening can be started with scapulo-thoracic muscles and then with glenohumeral dynamic stabilizers. Aerobic activity as bicycling should continue.

Phase 2: it starts when pain and inflammation are resolved. Strengthening can increase and approach the end range, with particular attention to the stretching of the posterior capsule. An elastic band can be used to help to strengthen every single muscle. Movements that cause pain are avoided. Strengthening of the scapulo-thoracic system should continue, as aerobic activity. When the athlete has achieved a good scapular and glenohumeral system, sport-specific movements can start.

Phase 3: normally, the athlete should have a pain-free range of motion. Eccentric activity is suggested, especially for posterior cuff and medial scapular muscle. The strengthening program can be progressed to full range and maximal resistance. Isokinetics exercise can be started for glenohumeral rotators, elevator muscles, and scapular muscles.

Phase 4: the athlete can return gradually to sport activity. Each sport has its specific activity: for example, pitchers perform an interval throwing program, swimmers perform low-intensity interval training, and tennis players start with forehands practice and then with backhands. The intensity is increased, until reaching pre-injury level, which is the target of this phase.

Outline exercise to preserve strength and motion should continue when the athlete comes back to activity.

22.4.2 Surgical Treatment

In patient with subacromial impingement, intact rotator cuff surgical treatment is indicated after several months of rehabilitation and activity modification failure. Generally, these criteria may be applied also to athletes. The surgeon must be sure that the cause of the shoulder pain is the mechanical supraspinatus outlet narrowing, because glenohumeral instability and labral pathology are more common, especially in shoulder pain of throwing athlete [1].

In partial rotator cuff tear, surgical indication is similar to those with an intact rotator cuff, but if MRI shows a lesion involving more than 50 % of the tendon thickness, nonoperative treatment may be shorted and the surgery proposed before 9 months [22–24]. Bursal-side tears may be more symptomatic then articular-side tears, and in this case surgical approach may be more aggressive. During diagnostic arthroscopy surgeon should check both the depth of the lesion and the quality of remaining tendon: it is necessary to check the rotator cuff insertion from both the glenohumeral joint side and the subacromial bursal side. Diagnostic arthroscopy is followed by arthroscopic acromioplasty if the surgeon finds bony supraspinatus outlet impingement. Debridement is suggested in articular-side partial tears less than 50 % and in bursal-side lesion less than 25 %. In other cases, partial rotator cuff tears are repaired [25].

In complete rotator cuff tears, if a 6- to 12-week trial of nonoperative treatment and activity modification fails, surgical approach is suggested, especially in young throwing athletes to permit a return to competition [1]. In overhead athletes most of lesions are small (1–2 cm or one tendon) and minimally retracted: surgical technique is often mini-open or arthroscopic repair. Instead rotator cuff injury in contact athletes is usually larger than 2 cm or one tendon and retracted: in this case some authors suggest open repair [21]. Our position is that both open and arthroscopic surgical techniques may be practiced, but arthroscopic treatment is preferred for its decreased scarring and minor deltoid morbidity, which may influence the postoperative rehabilitation and return to pre-injury level.

22.5 Rehabilitation and Return to Play

Return to sport activity, possibly at the same level before the injury, is the athletic rehabilitation target.

Rehabilitation after arthroscopic surgery without rotator cuff repair is the same of nonoperative treatment. In case of rotator cuff repair, postoperative rehabilitation is divided into four phases [1].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree