CHAPTER 6 Setup and Patient Positioning

PREPARATION

Proper operating room setup and patient positioning are fundamental steps to achieving consistent results with shoulder arthroscopy. Most practitioners learn shoulder arthroscopy based on the preferences of their attending physicians in a residency or fellowship training program. For a well-supervised and sustained hands-on learning experience, I strongly recommend visiting and watching those adept in shoulder arthroscopy and, when appropriate, attending courses at the Orthopaedic Learning Center and those offered by the Arthroscopy Association of North America in Rosemont, Illinois (Fig. 6-1).1 The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons2 also offers courses every year. These include basic to advanced shoulder arthroscopy, as well as arthroscopic courses focusing on other joints. Many choices and decisions depend on surgeon preference, and it is critical to experience as many alternative procedures and techniques as possible so that the shoulder arthroscopist can choose the one that works best. Be systematic, thorough, and consistent in your approach. As the leader in the operating room, expend the time and effort to educate the surgical staff and operating room personnel regarding your positioning, instrumentation, and technical preferences.

SETUP

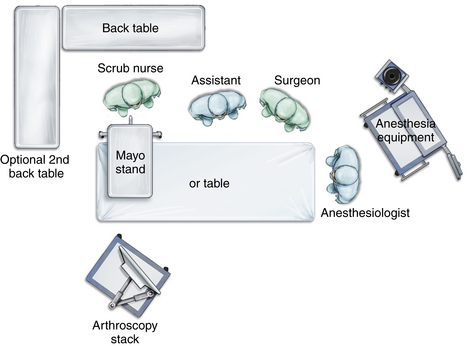

Operating Room

The operating room itself should be large enough to allow space for the surgeon to move about freely, one or possibly two assistants, a scrub nurse, the anesthesiologist and anesthesia equipment, the operating room table, arthroscopy stack with video and power equipment (Fig. 6-2), one or two back tables, and one or two Mayo stands. Most standard operating rooms are sufficient for shoulder arthroscopy. If there are windows in the room, they should be covered with darkening blinds. At the surgeon’s discretion, the room lights may be darkened to allow better viewing of the video without reflections.

Instrumentation and Equipment

An arthroscopy cart or stack is arranged so that the monitor is facing and within easy view of the operating surgeon. Ideally, two video monitors are available and are placed facing each other on either side of the operating room table so that the surgeon has a clear and constant view of the surgery if he or she moves around the head of the patient during the procedure. A Mayo stand is placed near the patient’s shoulder and holds the basic and most frequently used instruments and equipment: an arthroscope and camera, cannulas, trocars, probes, shaver and/or burr, and radiofrequency device. The back table is placed within easy reach of the scrub nurse and will hold instruments and equipment that are needed but less frequently used (Fig. 6-3).

PATIENT POSITIONING

Disadvantages include the need to lift and turn the patient, the possibility of excessive distraction across the glenohumeral joint, with the inherent possibility of nerve damage, limited access to the anterior shoulder, the tendency for the suspension apparatus to place the patient’s arm in internal rotation (possibly resulting in loss of external rotation postoperatively), and the need to reposition the patient if an open anterior approach is needed.3 A vacuum bean bag is placed on the operating room table prior to patient positioning (Fig. 6-4). The patient is moved onto the table and the center of the bean bag in the supine position. Following the induction of anesthesia, both shoulders are examined, most often checking the range of motion and for signs of instability. The patient is then turned onto the unaffected side, directly in the center of the operating room table and the bean bag. In cases in which examination of the contralateral extremity is unnecessary, the patient can position himself or herself in the lateral decubitus position prior to intubation. The patient can find the most comfortable position, and the bean bag is then inflated. Intubation can be easily achieved in the lateral decubitus position and self-positioning can save time and number of staff needed, and allows those with somatic concerns an opportunity to provide feedback about their degree of comfort.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree