63

Scapholunate Instability

Steven F. Viegas and Manuel F. DaSilva

History and Clinical Presentation

A 45-year-old right hand dominant railroad worker fell at work onto his right hand. He developed pain in the wrist, a painful snapping sensation, and weakness of pinch and grip strength in that hand. He was treated with an extended period of splinting and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory medications without success. Subsequent radiographs demonstrated a scapholunate dissociation with dorsal intercalated segment instability (DISI) deformity. Wrist arthrogram demonstrated a disruption in the scapholunate interosseous ligament. The patient was referred for further treatment 9 months after the injury.

Physical Examination

The patient had localized tenderness at the dorsal aspect of the scapholunate joint. Scaphoid stress test resulted in pain and an audible and palpable snapping. Range of motion of the wrist was full and comparable to the contralateral side. Pinch and grip strengths were ∼45% of the contralateral side.

Physical examination should include both extremities; unless otherwise indicated, the contralateral side is an excellent measure of the patient’s normal baseline regarding range of motion and level of physiologic laxity. When attempting to assess whether or not scapholunate dissociation exists, one should pay particular attention to any tenderness at the level of the scapholunate joint, particularly at the dorsal aspect of the scapholunate joint, on average located approximately 1 cm distal to Lister’s tubercle. The Watson test or scaphoid stress test is also useful to assess whether or not there exists any abnormal mobility of the scaphoid. Occasionally, a painful, audible snap can be elicited during this test.

Diagnostic Studies

Radiographs demonstrated a foreshortened scaphoid with a positive signet ring sign with an increased scapholunate joint space on an anteroposterior (AP) view (Fig. 63–1A). There was a DISI alignment on the lateral radiograph (Fig. 63–1B). Previous wrist arthrogram demonstrated communication between the midcarpal and the proximal wrist joints through the scapholunate joint.

Appropriate radiographs should be obtained, including standard posteroanterior (PA), lateral, radial deviation, ulnar deviation, oblique, and AP supinated clenched fist views of the wrist and hand. Radiographs of the contralateral wrist can be obtained and used for comparison. A significant scapholunate dissociation will result in a carpal instability dissociative (CID) type of lesion that typically will result in a DISI pattern of carpal malalignment. This carpal instability pattern has been well described regarding its particular radiologic features, which include the following:

PEARLS

- Identify visually and/or by palpation the location of the DIC ligament before making the initial capsular incision.

- Anatomic reduction of the scapholunate joint is critical and needs to be confirmed visually from both the mid- and radiocarpal joints as well as radiographically.

- It is important to understand the lateral “V” construct, which consists of the dorsal radiocarpal ligament, distal intercarpal ligament, and dorsal components of the scapholunate and lunotriquetral ligaments, that allows indirect dorsal stability of the scaphoid throughout its range of motion.

PITFALLS

- Wrists with lunotriquetral coalitions can have a widened scapholunate joint space without having a scapholunate dissociation.

- A patient can have a positive arthrogram showing dye leakage through the scapholunate joint and/or arthroscopic identification of a tear of the membranous portion of the scapholunate ligament without having scapholunate instability.

- Use of an inadequate number and/or size of K wires may result in pin breakage or bending or suboptimal immobilization of the carpus.

- Scapholunate gap: The intercarpal distance between the scaphoid and lunate on the AP radiograph is increased, compared with the other intercarpal spacing. A scapholunate gap greater than 3 mm is considered diagnostic of a scapholunate dissociation. This scaphoid gap has been called the “Terry Thomas” sign after the famous English film comedian’s dental diastema. This increase in the scapholunate intercarpal distance is most noticeable, both in biomechanical and clinical studies, in the AP supinated clenched fist radiographic view.

- A shortened scaphoid: The scaphoid assumes a flexed posture as a result of its dissociation from the surrounding carpus and assumes a shorter appearance on the PA and AP radiographic views.

- The cortical ring sign: The flexed posture of the scaphoid results in an end-on view of the scaphoid tubercle/distal scaphoid, which results in this more prominently visualized circular cortex of the scaphoid.

- DISI pattern of the carpus: The scaphoid assumes a flexed and dorsally subluxed posture, the lunate assumes an extended and volar subluxed posture, and the capitate lies in a flexed posture.

- Taleisnik’s “V” sign: The intersection of the volar edge of the scaphoid outline when the scaphoid is flexed intersects with the volar margin of the radius at a more acute angle than the normal wrist in which there is a more gentle or wide C-shaped pattern of intersection.

Arthrography can be utilized to assess the presence of ligamentous disruptions of the wrist. A wrist arthrogram, although helpful to identify ligamentous disruptions, is not able to characterize the size or degree of ligamentous disruption. Also of note is the fact that dissections of the wrist in cadavers demonstrate a 28% incidence of scapholunate interosseous ligament disruptions. In the dissections where both left and right wrists were evaluated, it was noted that if a scapholunate interosseous ligament disruption was seen on one side, there was a 66% incidence of disruption of this ligament on the contralateral side. Therefore, although reasonable as part of the workup, a positive arthrogram should not, in and of itself, be considered pathognomonic for scapholunate instability, particularly in the older population.

Differential Diagnosis

Scapholunate dissociation

Partial tear of the scapholunate interosseous ligament

Occult dorsal wrist ganglion

Impingement syndrome

Physiologic laxity

Lunotriquetral coalition

Diagnosis

Scapholunate Instability

One should attempt to determine in the history if there was any significant degree of trauma resulting in sufficient force to disrupt the normal anatomy of the wrist. Most typically, the pathomechanics resulting in a scapholunate dissociation includes a hyperextension force to the wrist with concomitant forearm pronation and intracarpal supination.

Arthroscopy

If a patient has a history, physical examination, and diagnostic workup that are consistent with scapholunate dissociation but the radiographs are equivocal, or the question of any articular damage or degenerative changes remains, the treatment approach that is offered to the patient is a manual examination under anesthesia and an arthroscopic examination, including proximal wrist and midcarpal joint examinations. Wrist arthroscopy can assist in confirming whether or not the disruption is acute in nature. Additionally, any concomitant chondral or osteochondral lesions can be identified.

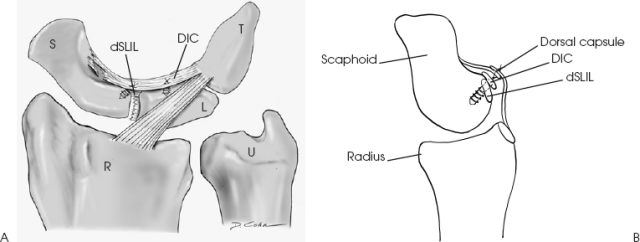

There have been preliminary reports of treatment of acute scapholunate dissociation by arthroscopically assisted closed reduction and percutaneous pinning of the scapholunate dissociation. If this treatment obtains some success, we believe that it is the result of an anatomic reduction of the scapholunate articulation and adequate healing of the dorsal segment of the scapholunate interosseous ligament (dSLIL) complex, the dorsal intercarpal (DIC) ligament to the dorsal aspect of the scaphoid, and the DIC to the dorsal aspect of the lunate. Although arthroscopically assisted closed reduction and percuta neous pinning of the scapholunate dissociation is offered as an alternative treatment, our treatment of choice is to confirm the diagnosis and the absence of degenerative changes, and once confirmed, to proceed to an open reduction and repair/reattachment of the dorsal component of the scapholunate interosseous ligament and of the DIC ligament, often to both its scaphoid and its lunate insertions/attachment sites.

Nonsurgical Management

In a scapholunate dissociation, the forces acting upon the scaphoid and lunate are significant and we believe cannot be adequately treated by closed treatment and cast immobilization alone if a DISI exists. Nor do we feel that closed reduction and percutaneous pin fixation is an adequate treatment, although arthroscopic-assisted reduction and percutaneous pin fixation may offer a better assessment of whether or not anatomic reduction is obtained than plane radiographs. If there is no carpal instability, nonsurgical management with immobilization and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory medications can be beneficial.

Surgical Management

The patient is placed in the supine position with the hand on an arm table. A tourniquet is placed on the upper arm. Either regional or general anesthesia is used. Initially, manual examination of the involved wrist is performed, followed by an arthroscopic examination of the proximal wrist joint and midcarpal wrist joint, if appropriate. The arthroscopic examination is performed with the hand in the upright position and with the assistance of traction. Once the diagnosis of scapholunate dissociation and the absence of degenerative changes is confirmed, the extremity is taken out of the traction and placed in pronation on the hand table. The surgical approach utilizes a dorsal longitudinal incision made over the dorsum of the wrist just ulnar to Lister’s tubercle. The skin incision is carried down to the extensor retinaculum. The dorsal venous complex of the wrist should be saved whenever possible, and the dissection plane is extended radially and ulnarly over the extensor retinaculum. A step-cut incision is made in the extensor retinaculum, leaving a radial and an ulnarbased flap. The terminal branch of the posterior interosseous nerve is identified at the floor of the fourth dorsal compartment lying immediately to the ulnar side of the septum separating the third and fourth compartments. A segment of the terminal branch of the posterior interosseous nerve is harvested, making sure to resect the nerve proximal to the distal end of the radius. The extensor tendons are retracted and a transverse incision is made through the wrist capsule just proximal and parallel to the DIC ligament. The DIC is often not easily identified from the dorsal approach, and running a probe or closed forceps from distal to proximal over the dorsal capsule helps isolate the thickened edge of the tissue, which is the DIC ligament. The capsular incision is then extended proximal and obliquely parallel to the radial aspect of the dorsal radiocarpal ligament. The DIC ligament can be reflected distally if it is an acute injury. If it is a chronic injury, the DIC ligament has typically contracted and already lies distal to its normal level of attachment to the lunate and the dorsal groove of the scaphoid. Most typically, the central, more membranous portion of the scapholunate interosseous ligament and the more substantial dorsal distal portion of the scapholunate interosseous ligament complex are usually avulsed off the scaphoid. The DIC ligament is often avulsed off the dorsal groove of the scaphoid and it is also often detached from the dorsal aspect of the lunate. The proximal wrist and midcarpal joints are examined through the capsular incisions for any osteochondral or chondral lesions. Any free fragments are excised. A trial reduction of the scapholunate joint is performed manually, and, if there is any difficulty in obtaining the reduction, 0.062-inch-diameter Kirschner wires (K wires) can be placed dorsally in the scaphoid and in the lunate and used as “joysticks” to assist in the reduction. While maintaining the scapholunate reduction, 0.045-inch-diameter K wires are used to percutaneously pin the scapholunate joint both from the radial and from the ulnar sides to maintain the reduction.

Once the scapholunate joint has been pinned, radiographs are obtained to confirm the reduction in both AP and lateral projections. Once the reduction has been confirmed radiographically, a 2.0- or 2.5-mm suture anchor is placed in the dorsal rim of the proximal half of the scaphoid in the area where the dorsal segment of the scapholunate interosseous ligament and the DIC ligament have been avulsed. Another suture anchor is placed at the dorsal aspect of the lunate, if the DIC ligament has been avulsed off the lunate (Fig. 63–2A). The suture attached to the scaphoid suture anchor is utilized to reattach the dSLIL and the DIC to their origin on the scaphoid. The suture attached to the lunate suture anchor is utilized to reattach the DIC to its origin on the lunate. If the injury is chronic, and the DIC has contracted and lies distal to its normal location, then the DIC is released distally while maintaining its triquetral attachment and is relocated and attached to the lunate and scaphoid. Once these sutures are tied, the same sutures are used to repair the capsular incision with a slight vest-over-pants imbrication (Fig. 63–2B).

Reattachment of the proximal membranous portion of the scapholunate interosseous ligament has also been described. This portion of the ligament, however, is often seen to be disrupted or attenuated in several cadaver dissections. Mechanically, it is not as substantial as the dorsal portion of the scapholunate interosseous ligament complex or the DIC ligament and is an intraarticular structure bathed in synovial fluid with questionable potential for healing. In addition, the degree of further dissection of the scaphoid to place the drill holes and sutures for reattachment of the membranous portion of the scapholunate interosseous ligament is more substantial and of questionable benefit.