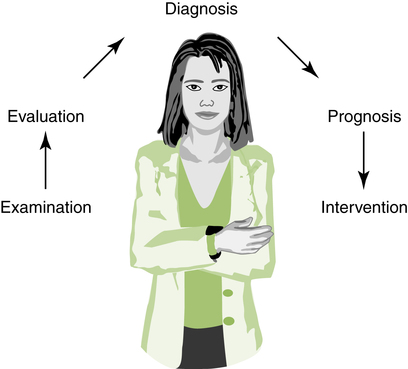

After reading this chapter, the reader will be able to: In the past two decades, the demand for physical therapists (PTs) and physical therapist assistants (PTAs) and the recognition and reimbursement for services they provide have evolved dramatically. This transformation has resulted from several trends and outside influences, including the aging population, federal legislation entitling children in public schools to health care, a burgeoning interest in personal fitness, and actions taken by insurance companies and the government to contain the rising cost of health care. PTs and PTAs have had to adapt to these rapid and extensive changes, which at times have been frustrating to comprehend and accommodate. A Putnam Investments advertisement aptly summarizes these sentiments: “You think you understand the situation, but what you don’t understand is that the situation just changed.”1 The profession of physical therapy has succeeded and will continue to succeed. We have followed several of the ground rules proposed by Price Pritchett, including becoming quick-change artists, accepting ambiguity, and holding ourselves accountable for our individual actions.1 To provide a framework for understanding the profession in the context of change, this chapter examines the diverse and shifting roles of PTs, the breadth of services provided, and the variety of employment settings where these services exist. Recent demographic data and information on employment activities and conditions are presented. More specific descriptions of the functions performed by PTs and PTAs in the delivery of services are presented in Part 2 of this text. The primary role of a PT involves direct patient care. Although PTs engage in many other activities and in some cases no longer participate in clinical practice, patient care remains the predominant employment activity. For this reason, the Standards of Practice for Physical Therapy is perhaps the foremost core document approved by the House of Delegates of the American Physical Therapy Association (APTA). As noted in the Preamble to the document, “These Standards are the profession’s statement of conditions and performances that are essential for provision of high quality professional service to society, and provide a foundation for assessment of physical therapist practice.”2 The sections of the Standards are as follows: These roles are described later in the chapter. Individuals who seek health care may move through multiple levels of providers as they enter the system and may eventually reach a specialist. The first level of care, primary care, is defined as the level of health care delivered by a member of the health care system who is responsible for the majority of the health needs of the individual.3 This level of care usually, but not always, is provided by the first health care provider in contact with the recipient. Family and community members may also provide care at this level. Secondary care is provided by clinicians on a referral basis—that is, after the individual has received care at the primary level. In tertiary care the service is provided by specialists, commonly in facilities that focus on particular health conditions. These services may also be provided on a referral basis. PTs are engaged in practice at all three levels of care. Physical therapy is most often delivered by referral as secondary or tertiary care. Tertiary care may be provided in a highly specialized unit, such as a burn care center. The entry point for an individual seeking physical therapy services, however, is shifting to primary care. This is described as direct access. As Burch states, the phrase direct access is preferred to practice without referral, which implies no regard or interest in the critical services provided by practitioners in other disciplines.4 In the District of Columbia and in the 45 states in which direct access is legal, individuals may obtain physical therapy services without having to obtain a referral from another health care provider. In this role the PT serves as a gatekeeper for further health care services. PTs, by virtue of their extensive education in normal body structure and function, are well qualified to provide services that prevent or limit dysfunction. These services may be categorized as screening or prevention activities.3 In screening, the PT determines whether further services are needed from a PT or other health care professional. A common example is posture analysis of schoolchildren to determine whether scoliosis may be present. In prevention activities the PT provides services designed to prevent, limit, or reduce pain and dysfunction. These programs generally include several components: a history questionnaire, medical screening and evaluation, consultation, exercise performance, and reassessment.5 The history questionnaire provides information about general health and related habits. A comprehensive medical and physical evaluation is necessary to establish a baseline and design a program. Consultation is provided individually or in a group to describe the results of the evaluation and compare them with norms. The results of the evaluation are used to design exercise programs, which may be conducted at home, at work, or at a health-related facility. Periodic reassessment ensures program effectiveness and serves as a motivating factor. Recently the business and health care industries have been cooperating to provide programs that will prevent injury and disease and thereby reduce health care costs while increasing productivity. PTs are directly involved in health promotion and wellness activities, both as consultants for establishment of programs and as providers of health care on site or in a health-related facility. The PT may conduct an analysis of ergonomics at the work site and perform a functional capacity evaluation Ergonomics is the relationship among the worker, the worker’s tasks, and the work environment.3 After an ergonomic assessment, the therapist may design a work-conditioning program or work-hardening program. The work-conditioning program focuses on the physical dysfunction, whereas the work-hardening program includes this aspect in addition to behavioral and vocational management. The goal of both programs is to return the individual to work. The Guide to Physical Therapist Practice3 has been instrumental in defining and describing what PTs do as clinicians. These activities have been summarized in the patient/client management model (Figure 2-1). This model reflects the process of gathering information, designing a plan of care, and implementing that plan to result in optimal outcomes for the patient/client. The first component of the patient/client management model, examination, is the process of gathering information about the past and current status of the patient/client. It begins with a history to describe the past and current nature of the condition or health status of the patient/client. Sources for this information include the patient/client, caregivers, other health professionals, and medical records. A systems review is then conducted to obtain general information about the anatomic and physiologic status of the musculoskeletal, neuromuscular, cardiovascular/pulmonary, and integumentary systems, as well as the cognitive abilities of the patient and client. This review provides information to determine if referral to other health professionals is necessary. In the final component of the examination, tests and measures, the therapist selects and performs specific procedures to quantify the physical and functional status of the patient/client. A list of these tests and measures as presented in the Guide appears in Table 2-1, and some examples are shown in Figures 2-2 through 2-7. Note that these activities involve observation, manual techniques, simple and complex equipment, and environmental analysis. Table 2-1 Tests and Measures Used in a Physical Therapy Examination Data from American Physical Therapy Association (APTA): Guide to physical therapist practice, rev ed 2, Alexandria, Va, 2003, APTA.

Roles and Characteristics of Physical Therapists

Describe the roles of the physical therapist in primary, secondary, and tertiary care

Describe the roles of the physical therapist in primary, secondary, and tertiary care

Describe the roles of the physical therapist in prevention and health promotion

Describe the roles of the physical therapist in prevention and health promotion

Describe the components of the patient/client management model

Describe the components of the patient/client management model

Describe general features of tests and measures and procedural interventions used in physical therapy

Describe general features of tests and measures and procedural interventions used in physical therapy

Describe other professional roles of the physical therapist in the areas of consultation, education, critical inquiry, and administration

Describe other professional roles of the physical therapist in the areas of consultation, education, critical inquiry, and administration

List and describe the demographic characteristics of physical therapists

List and describe the demographic characteristics of physical therapists

Roles in the Provision of Physical Therapy

Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary Care

Prevention and Health Promotion

Patient/Client Management Model

Examination

Test or Measure

Description

Aerobic capacity/endurance

Ability to use the body’s O2 uptake and delivery system

Anthropometric characteristics

Body measurements and fat composition

Arousal, attention, and cognition

Degree of responsiveness and awareness

Assistive and adaptive devices

Equipment to aid in performing tasks

Circulation (arterial, venous, lymphatic)

Analysis of blood and lymph movement to determine adequacy of cardiovascular pump, oxygen delivery, and lymphatic drainage

Cranial and peripheral nerve integrity

Assessment of sensory and motor functions of cranial and peripheral nerves

Environmental, home, and work barriers

Analysis of physical restrictions to functioning in the environment

Ergonomics and body mechanics

Analyses of work tasks and postural adjustment to perform tasks

Gait, locomotion, and balance

Analyses of walking, moving from place to place, and equilibrium

Integumentary integrity

Health of the skin

Joint integrity and mobility

Assessment of joint structure and impact on passive movement

Motor function

Control of voluntary movement

Muscle performance

Analysis of muscle strength, power, and endurance

Neuromotor development and sensory integration

Evolution of movement skills and integration of information from the environment

Orthotic, protective, and supportive devices

Determination of need for fit of devices to support weak joints

Pain

Analysis of intensity, quality, and frequency of pain

Posture

Analysis of body alignment and positioning

Prosthetic requirements

Selection, fit, and use of prostheses

Range of motion

Amount of movement at a joint

Reflex integrity

Assessment of developmental, normal, and pathologic reflexes

Self-care and home management

Analysis of activities necessary for independent living at home

Sensory integrity

Assessment of peripheral and central sensory processing, awareness of movement, and position

Ventilation and respiration/gas exchange

Assessment of movement of air into and out of the lungs, exchange of gases, and transport of blood to perform activities of daily living and exercises

Work, community, and leisure integration or reintegration

Analyses to determine whether the patient/client can assume a role in community or work

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Roles and Characteristics of Physical Therapists