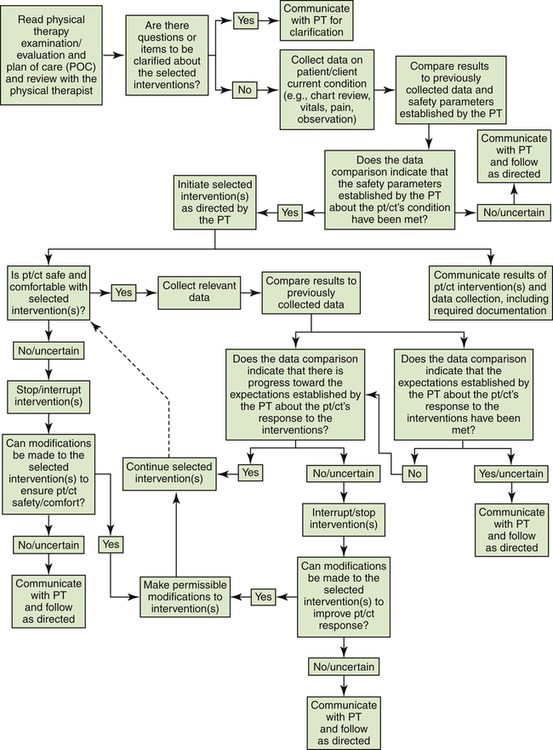

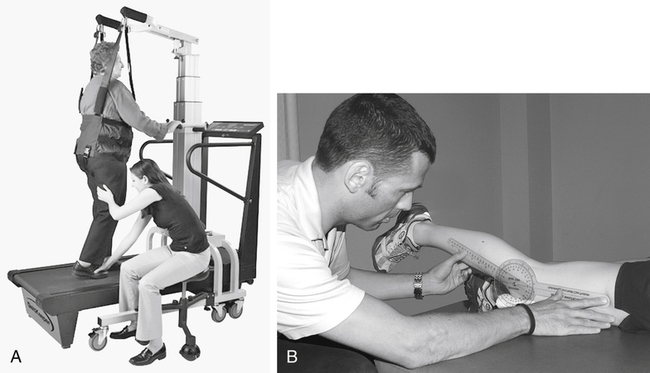

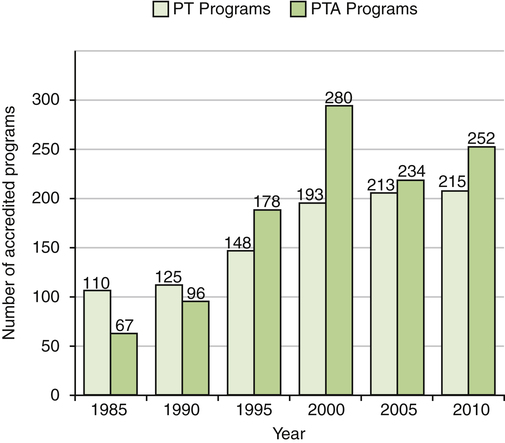

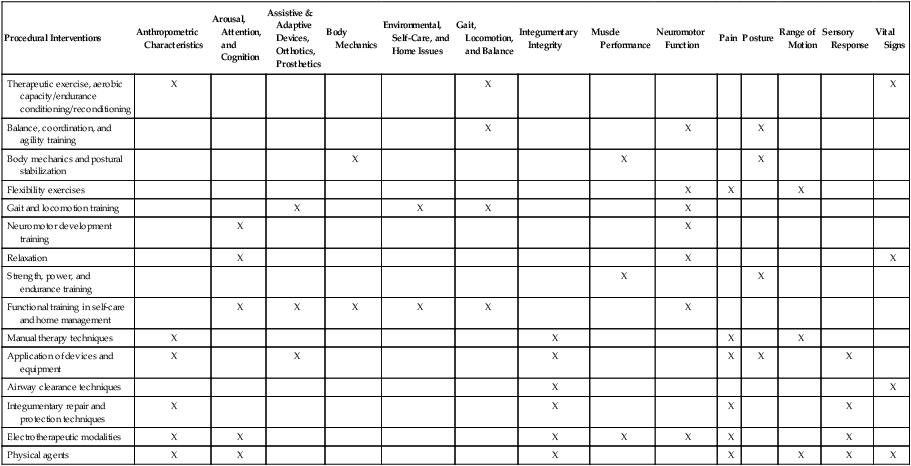

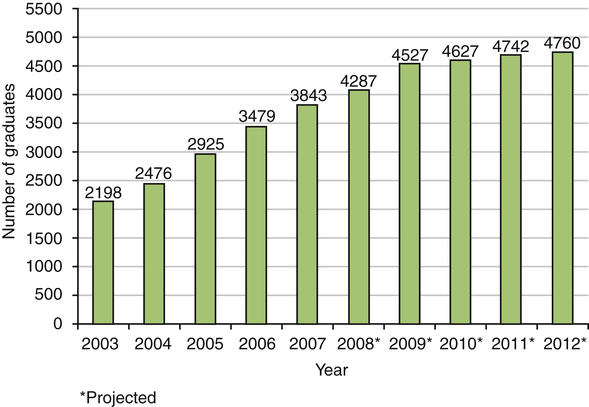

John E. Kelly and Pamela D. Ritzline After reading this chapter, the reader will be able to: Advisory Panel of Physical Therapist Assistants Affiliate Special Interest Group (ASIG) National Assembly of Physical Therapist Assistants physical therapist assistant (PTA) physical therapy aides or technicians physical therapy interventions Physical Therapist Assistant Caucus physical therapist assistant members recognition of advanced proficiency for the PTA Representative Body of the National Assembly (RBNA) sole extender of the physical therapist A growing demand for physical therapy services spurred the creation of the physical therapist assistant (PTA) in the 1960s. Since the inception of this category of health care provider, debate and controversy have existed in determining the function of the PTA in physical therapist practice. As the American Physical Therapy Association (APTA) strives to achieve Vision 2020,1 the role of the PTA continues to be refined in realizing that vision.2 The advancement of physical therapy to a doctoring profession may necessitate adjustments to the role of the PTA. Outside influences such as state and federal legislation, demand for physical therapy services, and payment policy will affect any adjustments necessary for the PTA to remain a vital component of physical therapist practice. Defining the term physical therapist assistant provides a starting point to understanding the role of the PTA. A PTA is a health care provider whose function is to assist the PT in the provision of physical therapy services in compliance with laws and regulations governing the practice of physical therapy (Box 3-1).3,4 As described in Chapter 1, the polio epidemic and World War II collectively reinforced the need for physical therapy services. Health care legislation, particularly the Hill-Burton Act of 1946 and the Medicare and Medicaid legislation of 1965, led to increased access to physical therapy. This increased access created tremendous demand for physical therapy services that could not be met, and a shortage of PTs resulted.5 Although some hospitals and physical therapy clinics created structured on-the-job training for nonprofessional staff to help meet the demand,6,7 the need for formally educated and regulated support personnel quickly became apparent.8,9 Before any action on the part of the APTA, several agencies began to investigate the creation of formalized training of support personnel in physical therapy. Some of these agencies included the American Association of Junior Colleges, the U.S. Department of Labor, the U.S. Department of Health, vocational schools, physician groups, hospitals, rehabilitation centers, nursing homes, and state health departments.10–12 The APTA became concerned about the development of training programs without the benefit of physical therapy leadership and input, and in 1964 the APTA House of Delegates (HOD) established a task force to investigate the role of support personnel and the criteria for PTA education programs.10 In 1967 the task force submitted a proposal for the creation of physical therapy assistants (the title was later changed to physical therapist assistants to clarify the role that PTAs play in the provision of physical therapy interventions, to assist PTs).13 On July 5, 1967, the APTA HOD adopted the policy statement “Training and Utilization of the Physical Therapy Assistant,”14 essentially giving birth to the PTA. This policy statement included a definition of the assistant, the supervisory relationship with the PT, and the functions that PTAs could perform. Furthermore, the statement established the need for accreditation of 2-year associate’s degree education programs by what is now the Commission on Accreditation in Physical Therapy Education (CAPTE). Finally, the statement included support for mandatory licensure, and APTA membership eligibility. Two PTA education programs were created in 1967 as a result of this action, at Miami Dade College in Florida and St Mary’s Junior College (now known as the Minneapolis Campus of St Catherine University) in Minnesota. Two years later, in 1969, these institutions graduated the first 15 PTAs.15 Development of new PTA education programs was prolific; they eventually exceeded the number of PT education programs (Figure 3-1). As more PTA education programs were established, variability in the preparation of PTA students became evident. In 1975, in an effort to improve uniformity of PTA education programs, the APTA HOD approved The Essentials of an Accredited Education Program for Physical Therapist Assistants.16 Despite these efforts, debate among physical therapy practitioners and educators regarding the appropriate education, utilization, and supervision of PTAs continued throughout the 1980s and 1990s,17 leading the APTA Department of Education to organize the Coalition on Consensus for Physical Therapist Assistant Education in 1995.18 This landmark series of conferences eventually led to the development of A Normative Model of Physical Therapist Assistant Education, initially approved by the APTA HOD in 1999.19 This comprehensive document, alongside the CAPTE document Evaluative Criteria for Accreditation of Education Programs for the Preparation of Physical Therapist Assistants16 and the Guide to Physical Therapist Practice,20 established increased consistency in the educational preparation and clinical utilization of PTAs. The physical therapy profession overcame significant obstacles in its growth and development. The Balanced Budget Act of 1997, introduction of the prospective payment system (PPS) under Medicare, and restricted access to physical therapy services resulting from managed care contracts combined to cause a declining job market for PTs and PTAs, as well as for many other health care providers.21 As a result, the development of new PTA education programs eventually experienced a decline, and some programs were terminated voluntarily (see Figure 3-1). Fortunately, the job market improved in response to continued high demand for physical therapy services and as a result of the expansion of physical therapists’ roles. The role of the PTA continued to be refined through actions of the APTA. In 2000 the position statement Procedural Interventions Exclusively Performed by Physical Therapists22 defined interventions that were beyond the scope of work of the PTA. In 2003, in response to recommendations by a task force to study the role of the PTA, the APTA Board of Directors (BOD) initiated work to define the role of the PTA within the APTA’s Vision 2020.23 In 2007, as part of the revisions to A Normative Model of Physical Therapist Assistant Education, a PTA clinical problem-solving algorithm was produced.19 In 2008, after extensive research, the APTA BOD adopted the document Minimum Required Skills of Physical Therapist Assistants at Entry-Level24; and in 2009 the APTA BOD issued a resolution reaffirming that the PTA is the sole extender of the physical therapist, meaning that the PTA is the “only individual permitted to assist a physical therapist in selected interventions under the direction and supervision of a physical therapist,”4 that the associate’s degree is the appropriate degree requirement for the PTA, and that PTAs have “potential for ongoing education after licensure/regulation within the realm of interventions.”25,26 This section reviews the educational level, accreditation requirements, and curriculum for PTA education programs. A Normative Model of Physical Therapist Assistant Education provides an overview of the purpose of these education programs (Box 3-2). PTAs are licensed or otherwise regulated in 48 states.27 To sit for the licensure examination in most states, a candidate must be a graduate of a PTA education program accredited by CAPTE. CAPTE is the only accreditation agency recognized by the U.S. Department of Education and the Council for Higher Education Accreditation to accredit PT (professional level) and PTA education programs in the United States. Although appointed by the APTA Board of Directors, CAPTE functions independently in all its actions, including making program accreditation status decisions.28 Although some variability in the structure and design of PTA education programs exists to allow for consistency with the mission and community needs of each university or college, CAPTE dictates the minimum requirements.16 PT professional education programs prepare PT students to perform all aspects of the patient/client management model, including examination, evaluation, diagnosis, prognosis, and intervention.20 The educational requirements within PTA curricula are designed to prepare the PTA students to assist the PT in the delivery of physical therapy interventions and the associated data collection. The curricula for PTA education programs contain many similarities to those for PT education programs, including general and foundational content as well as technical and clinical components. Basic sciences within the general and foundational content include math, chemistry, physics, biology, anatomy and physiology, kinesiology, and pathology, although some variability exists. These courses provide foundational knowledge for further instruction in the application of skilled interventions. The technical education component of the curriculum is designed to prepare the PTA student to perform physical therapy interventions under the direction and supervision of the PT. These courses include instruction in intervention and associated data collection techniques (Table 3-1). Table 3-1 Interventions and Associated Data Collection Techniques Adapted from American Physical Therapy Association (APTA): A normative model of physical therapist assistant education: version 2007, Alexandria, Va, 2007, APTA. In addition to the didactic component of the curricula, clinical education is an important component of PTA education programs. CAPTE requires both integrated and terminal clinical experiences.16 The clinical education requirements include exposing the PTA student to a variety of practice settings and patient/client diagnoses. Clinical education practice settings are similar to those for PT students and may include acute care hospitals, rehabilitation centers, extended-care facilities, outpatient clinics, and school settings. The APTA provides guidelines,29,30 clinical assessment tools,31 and optional credentialing for PT and PTA clinical instructors.32 While participating in clinical education, the PTA student may be supervised by a PT or by a PTA; however, additional supervision and direction from the supervising PT are necessary when a PTA is the direct clinical instructor.33 Accreditation criteria emphasize the inclusion of career development and behavioral expectations in addition to the foundational knowledge and technical and clinical skills necessary to become a PTA. These expectations include self-reflection and cultural competence as well as accountability, altruism, compassion and caring, integrity, professional duty, and social responsibility, which the APTA has deemed Core Values.34 PTA program graduates are responsible for understanding resource management principles, including the concepts of time management, facility policy and procedures, service delivery models, reimbursement guidelines, regulatory requirements, economic factors, and health care policy, and how these principles affect patient/client care. PTA program graduates should be able to read and interpret professional literature and implement new concepts in their clinical work. Clinical problem solving includes the ability to adjust, modify, or discontinue an intervention within the plan of care established by the PT based on clinical indications.24 A graduate of a PTA program has the skills and knowledge to determine the effectiveness of the intervention; to adjust the intervention in order to improve the patient/client response, or for patient/client safety or comfort; and to document the outcome of the intervention. Refer to Figure 3-2 for a diagram of the clinical problem-solving process a PTA uses in ensuring patient/client safety and comfort while progressing toward established outcome goals. Some PTAs choose to become PTs, using their clinical knowledge as a head start toward completing the academic requirements of a professional-level PT program. Most PT professional education programs do not accept PTA coursework credits, but a limited number of “bridging” programs exist.35 The purpose of education programs bridging from PTA to professional-level PT education is to allow PTAs a unique opportunity to complete the degree requirements and become PTs in a decreased time frame than that required in traditional professional-level degree programs. This educational model allows PTAs to receive credit for their PTA coursework and clinical experience and apply it toward an entry-level Doctor of Physical Therapy degree. The recent trend of increasing numbers of PTA program graduates is a reflection of the ongoing shortage of physical therapy practitioners in the marketplace (Figure 3-3).36 Although the APTA has determined that the associate’s degree is the appropriate entry-level degree for the PTA,25 some controversy exists. Some within the physical therapy profession perceive an undesirable gap in educational levels between the PTA and the PT because the professional-level education of the PT has elevated to the doctorate at over 96% of the programs. Many barriers exist to increasing the entry-level education of the PTA, including the location of the predominance of PTA education programs in technical and community colleges that cannot confer bachelor’s degrees. However, proponents point to the salient qualities of an increased educational level, resulting in PTAs with an increased skill level and therefore the best prepared and most qualified individuals to assist PTs in the provision of selected patient/client interventions. While discussion is ongoing, any changes that may occur in the entry-level education of PTAs are speculative. Further discussion related to this topic can be found in the Trends section of this chapter. The PTA’s clinical role lies solely within the intervention component of the patient/client management model (see Figure 2-1). Figure 3-4 provides examples of a PTA performing an intervention (gait training using body weight–supported treadmill training [BWSTT]), and a data collection technique (joint range-of-motion measurement [goniometry]). Even when selected physical therapy interventions are delegated to a PTA, the PT remains responsible for the care, documentation, and outcomes related to that intervention. This responsibility highlights the importance of ongoing communication, and direction and supervision throughout the episode of care. Although clinical settings and situations differ greatly, regardless of the setting in which the service is provided, the decision to delegate selected interventions to a PTA is part of the clinical decision-making process of the evaluating PT.4 According to the APTA position statement Direction and Supervision of the Physical Therapist Assistant, delegation of selected interventions “requires the education, expertise, and professional judgment of a physical therapist” (Box 3-3).4 Determining the appropriate utilization of a PTA in a particular clinical setting is essential to ensure safe, legal, ethical, and high-quality patient/client care. Outcomes, efficiency of service delivery, and patient satisfaction can be enhanced by utilization of a PTA.37 For this to occur, the supervising PT must carefully consider the many factors influencing the suitability of delegation of selected interventions and the need for ongoing supervision and direction. These factors are discussed in the following sections.

The Physical Therapist Assistant

Identify historical milestones in the development of the role of the physical therapist assistant

Identify historical milestones in the development of the role of the physical therapist assistant

Distinguish between the roles of the physical therapist and the physical therapist assistant within the patient/client management model

Distinguish between the roles of the physical therapist and the physical therapist assistant within the patient/client management model

Describe physical therapist assistant educational requirements and models of delivery

Describe physical therapist assistant educational requirements and models of delivery

Discuss legal and ethical factors related to delegation of selected interventions and direction and supervision of physical therapist assistants

Discuss legal and ethical factors related to delegation of selected interventions and direction and supervision of physical therapist assistants

Describe the controversy regarding the physical therapist assistant in entry-level and continuing education, clinical work, and American Physical Therapy Association membership

Describe the controversy regarding the physical therapist assistant in entry-level and continuing education, clinical work, and American Physical Therapy Association membership

Explain how the American Physical Therapy Association provides for representation, and influences the clinical work of the physical therapist assistant

Explain how the American Physical Therapy Association provides for representation, and influences the clinical work of the physical therapist assistant

Discuss how current trends may influence the future of the physical therapist assistant

Discuss how current trends may influence the future of the physical therapist assistant

Definition

Origin and History

Education and Curriculum

Accreditation

Differentiation between Physical Therapist and Physical Therapist Assistant Education

Procedural Interventions

Anthropometric Characteristics

Arousal, Attention, and Cognition

Assistive & Adaptive Devices, Orthotics, Prosthetics

Body Mechanics

Environmental, Self-Care, and Home Issues

Gait, Locomotion, and Balance

Integumentary Integrity

Muscle Performance

Neuromotor Function

Pain

Posture

Range of Motion

Sensory Response

Vital Signs

Therapeutic exercise, aerobic capacity/endurance conditioning/reconditioning

X

X

X

Balance, coordination, and agility training

X

X

X

Body mechanics and postural stabilization

X

X

X

Flexibility exercises

X

X

X

Gait and locomotion training

X

X

X

X

Neuromotor development training

X

X

Relaxation

X

X

X

Strength, power, and endurance training

X

X

Functional training in self-care and home management

X

X

X

X

X

X

Manual therapy techniques

X

X

X

X

Application of devices and equipment

X

X

X

X

X

X

Airway clearance techniques

X

X

Integumentary repair and protection techniques

X

X

X

X

Electrotherapeutic modalities

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

Physical agents

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

Clinical Education

Behavioral Criteria

Clinical Problem Solving

Physical Therapist Assistant Education Program Models

One-plus-one (1+1) programs. Students must complete foundational general education content satisfactorily before being accepted into the PTA program. Once accepted, students complete the technical physical therapy content, including didactic, laboratory, and clinical education segments.

One-plus-one (1+1) programs. Students must complete foundational general education content satisfactorily before being accepted into the PTA program. Once accepted, students complete the technical physical therapy content, including didactic, laboratory, and clinical education segments.

Integrated 2-year programs. Students accepted into the program complete foundational and physical therapy requirements concurrently.

Integrated 2-year programs. Students accepted into the program complete foundational and physical therapy requirements concurrently.

Part-time programs. This model may have components of integrated or 1+1 programs. Class schedules are designed to allow students to continue working or to complete additional academic requirements (e.g., weekend programs). Some programs are designed to allow the PTA student to pursue a bachelor’s degree while completing the educational requirements of the PTA program.

Part-time programs. This model may have components of integrated or 1+1 programs. Class schedules are designed to allow students to continue working or to complete additional academic requirements (e.g., weekend programs). Some programs are designed to allow the PTA student to pursue a bachelor’s degree while completing the educational requirements of the PTA program.

The Future of Physical Therapist Assistant Education

Utilization

Delegation, Direction, and Supervision

The Physical Therapist Assistant