28

Repair and Reconstruction of Acute and Chronic Patellar Tendon Rupture

- A functional and intact extensor mechanism is required for normal gait and function of the lower extremity.

- Acute ruptures of the patellar tendon should be repaired as soon as possible to optimize the quality of the tissue and avoid quadriceps retraction and fibrosis.

- If surgical delay is necessary, a knee immobilizer can temporarily substitute for absent quadriceps function and allow for ambulation while surgery is scheduled.

- Chronic ruptures should be reconstructed if the patient has absent or poor quadriceps function. The patellar tendon tissue may need to be supplemented with autogenous or allograft tissue.

- Primary repair may need to be delayed if inadequate skin coverage is present to cover the defect or repair.

- Repair or reconstruction should be avoided in the presence of active infection. The addition of a suture or metallic foreign body complicates the healing of the infection.

- Neurologic injury to the femoral nerve that precludes active quadriceps function may also preclude any attempt at repair unless the nerve injury is expected to resolve.

- Extensive associated quadriceps injury in which the motor power would be at best grade 1 or 2 would be a relative contraindication to repair, and other surgical procedures such as fusion might be considered.

- In acute injuries, inspection may reveal a visible defect inferior to the patella, patella alta, asymmetric quadriceps size, and ecchymosis over the patellar tendon. Patellar tendon ruptures are frequently missed in the emergency room as anterior knee swelling may hide visual cues entirely!

- In acute injuries, palpation along the extensor mechanism should reveal a defect between the distal pole of the patella and the tibial tubercle. Comparison should always be made to the opposite side.

- Palpation should always include the patella and tibial tubercle to rule out avulsion injuries.

- In chronic injuries, swelling will be less prominent. Although a defect may be present, commonly it is filled with scar tissue in a lengthened position, and the only positive findings are of patella alta and poor quadriceps function.

- Function of the extensor mechanism should be tested bilaterally. Some extensor power may remain in the face of a complete patellar tendon rupture if the medial and lateral retinacula are still intact. Usually these patients still have motor weakness and an extension lag. Inability to extend the knee with palpable motor contraction is diagnostic of a rupture of the extensor mechanism.

- A complete knee examination should always be performed to rule out associated ligamentous injuries, patellar instability or other injuries in the extremity.

Diagnostic Tests

- Standard radiographs usually reveal patella alta. This is best seen on the lateral view. The examiner should carefully inspect the radiographs for the presence of avulsion injuries of the distal pole or the tibial tubercle. Bilateral views are important, especially in the case of chronic ruptures. Bilateral views will allow the surgeon to plan appropriate patellar height for repair.

- Ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging are rarely required but can provide added visualization of the extent of damage and assist with preoperative planning. In confusing or chronic cases, ultrasound may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis.

Differential Diagnosis and Concomitant Problems

- Patella fracture

- Quadriceps rupture

- Patellar dislocation

- Bilateral patellar tendon ruptures2, 8

a. Systemic lupus erythematosus

b. Rheumatoid arthritis

c. Chronic renal failure

d. Diabetes mellitus

e. Polyarthritis nodosus

f. Tuberculosis

g. Typhus

h. Syphilis

i. Xanthoma

j. Scarlet fever

k. Villonodular synovitis

l. Hyperparathyroidism

m. Osteogenesis imperfecta

- Isolated association with anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) or posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) injuries is exceedingly rare.

- Multiple ligament knee injuries (knee dislocations)

- Acute on chronic (patellar tendon rupture after chronic tendinosis)

- Correlation with anabolic steroids or injectable corticosteroids

Preoperative Planning, Special Instruments, and Positions

- A history should be carefully obtained preoperatively. Anabolic steroid use has been associated with muscular hypertrophy and an increased risk of tendon ruptures. Steroid injections directly into the tendon have been related to weakening and failure of the collagen tissue. Some oral quinolones have also been associated with an increased risk of tendon failure. A majority of patellar tendon ruptures have a prodrome of some patellar tendinosis or jumper’s knee. The latter is very important in preoperative planning as the tissue discovered at the time of surgery may be less than optimal for repair.

- Preoperative discussions should be held with the patient regarding the potential need for autogenous or allograft soft tissue supplementation if the quality of the tissue is poor.

- A tourniquet may be used during the repair or reconstruction. If so, it is recommended to use a sterile tourniquet so that the surgical approach can be more extensile. In addition, when the tourniquet is inflated, the knee should be flexed. This allows increased mobility of the quadriceps tendon for repair.

- The patient is placed in the supine position. The leg should be draped free to allow for some knee flexion to assist in transpatellar suture passage.

- If an avulsion injury is present that is large enough to tolerate a screw, then cannulated screws, reduction clamps, or AO screws may be used to internally fix the fragment.

- If the rupture is chronic or an extensive preexistent history of patellar tendinosis is present, preoperative discussions should include soft tissue supplementation with either autogenous hamstrings or allograft hamstring, patellar tendon, or quadriceps tendon. If more than 40% of the patellar tendon is involved with tendinosis, supplementation should be considered.

- Proximal patellar tendon ruptures require transpatellar fixation. Suture passing may require long drill bits and a Hewson suture passer. I like to use the long Beath needle from the ACL set, which facilitates drilling and suture passage in one step.

- Distal patellar tendon ruptures may not allow a strong soft tissue repair in the distal remnant. In this case, suture anchors may assist in soft tissue repair to the tibia. Numerous anchors are available; screw-type anchors have the best resistance to pullout.

- Selection of suture material is important, as maturity of the tendon repair may be delayed. Most absorbable suture will not provide strength long enough to allow range of motion early in rehabilitation. Pancryl may last long enough if an absorbable suture is desired. No. 5 nonabsorbable sutures are most commonly selected for their durability. More recently, ultra-strong woven sutures such as FiberWire (Arthrex Inc., Naples, FL) and SecureStrand (Smith and Nephew, Andover, MA) have grown in popularity.

- The primary patellar tendon repair is usually protected or supported by a circumferential adjunctive fixation. Circumferential wiring is the historical standard with a transtibial wire that extends above and around the patella. Although successful, it has been associated with wire failure, prominent hardware, and pain, necessitating later hardware removal. Other authors have suggested external fixation or soft tissues supplementation with hamstrings, iliotibial band, or allograft tissue even in primary cases. Three sutures of No. 5 Ticron or the more recently available Fiberwire and SecureStrand have excellent strength and a lower profile, obviating the problems associated with metal wiring and obviating the risk of grafttissue.

Surgical Technique, Pearls, and Pitfalls

- After sterile prep is performed, a sterile tourniquet is placed on the thigh. The thigh is flexed during tourniquet inflation to allow increased mobility of the extensor mechanism for repair.

- An anterior midline surgical approach to the knee is performed. The incision must extend from just above the patella to about 2 cm below the tibial tubercle. This provides adequate exposure for pin passage vertically through the patella and horizontally through the tibia.

- The defect in the patellar tendon is usually obvious and most commonly found at the distal pole of the patella. Medial and lateral dissection should be extended above the level of the retinaculum to document the extent of the retinacular injury and provide appropriate exposure for retinacular repair.

- The pattern of injury and the quality of patellar tendon tissue should be assessed.

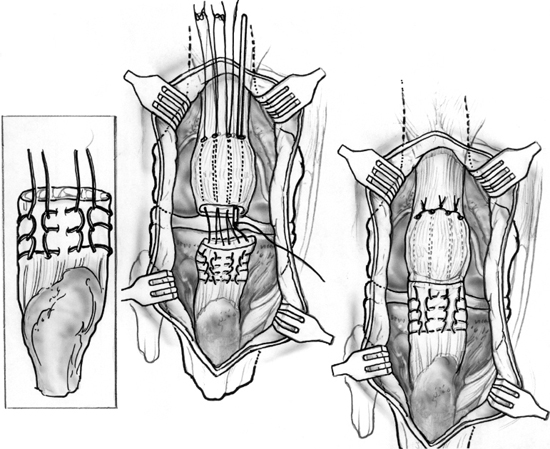

Acute Injuries from Distal Pole of Patella (Fig. 28-1)

- Distal pole of the patella is prepared with a burr or rongeur to expose bone. Some authors prefer a horizontal groove.

- The proximal end of the torn tendon is freshened, and three nonabsorbable sutures are placed in the medial, central, and lateral portions of the tendon, respectfully, in a whip stitch. Our preference is a Krackow stitch, which has been proven to have excellent pullout strength. The size of suture is minimally a No. 2, although No. 5 is commonly used.

- Three or four longitudinal drill holes are placed from the exposed distal pole of the patella, and the sutures are then passed from distal to proximal via a Hewson suture passer or a Beath needle from the ACL set. The advantage of a Beath or spade tip passing needle is that the wider tip allows for ease of passage for the bulky suture up the drill hole. It is helpful to flex the patient’s knee slightly so that the drill tips exit anterior through the quadriceps rather than parallel to it. Small longitudinal incisions in the quadriceps tendon are usually necessary to allow the surgeon to tie the sutures down to bone and minimize soft tissue entrapment.

- Prior to securing the repair, the sutures are pulled taut, and the patella tracking and patellar height are assessed. If acceptable, the first suture is tied while maintaining reduction with the other sutures. Once all tendon repair sutures are tied, the medial and lateral retinacula can be repaired with No. 0 absorbable suture. Absorbable suture is adequate here, as the primary tension forces are across the primary repair.

- Assuming good tissue quality and good-quality sutures, adjunctive fixation for primary patellar tendon repairs due to avulsions from the patella may not be necessary. Historically, the surgeon’s use of metallic wire was effective in protecting the repair; however, the problems associated with wire breakage and painful hardware were real. Our preference is to protect midsubstance repairs with a circumferential suture technique. A transverse tibial drill hole is placed slightly posterior and distal to the tibial tubercle in line with the patellar tendon fibers. Three No. 5 nonabsorbable sutures are passed with a Hewson suture passer and then weaved around the superior portion of the patella. The sutures are then tied, taking care to maintain the tension of the original repair. More recently, we have modified this technique to using a single strand of ultra-highstrength suture material (Fiberwire or SecureStrand), with equally successful results. For avulsions from the patella with good tissue repair, we have not provided adjunctive protective circumferential sutures and have noted no increase in failure risk.

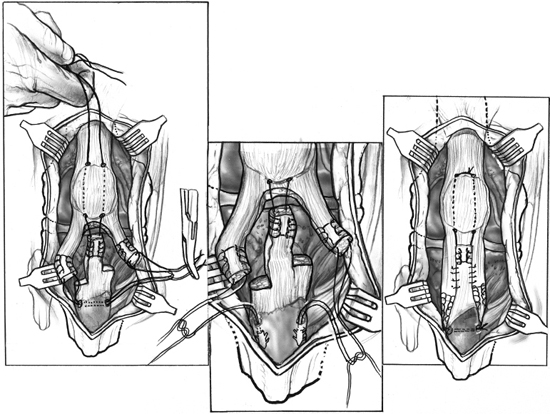

Acute Midsubstance Tears of the Patellar Tendon (Fig. 28-2)

- The surgical approach and adjunctive fixation is the same as for avulsions from the distal pole of the patella. Tears are rarely perfectly transverse and are usually composed of three or more vertically oriented strips.

- In midsubstance tears, the patellar tendon can be repaired with running interlocking sutures with a nonabsorbable suture. The distal-based tendon is reinforced with longitudinal drill holes through the patella, whereas the proximal-based tendon is fixed with a horizontal drill hole through the tibia or with suture anchors. The vertical component is then repaired with absorbable suture.

Acute Distal Injuries of the Patellar Tendon from the Tibial Tubercle

- Surgical approach is similar but may not be have to extend so proximal.

- Acute distal injuries of the patellar tendon are rare except in the skeletally immature, where avulsion of the tubercle can occur. These should be repaired with open reduction and internal fixation.

Figure 28-1 Acute repair of an avulsion of the patellar tendon from the distal pole of the patella with transpatellar sutures.

- Distal injuries of the patellar tendon with no significant bony component can be repaired with suture anchors and adjunctive protection of the repair as noted above. Our preference has been for the screw-type anchors in these procedures secondary to improved pullout strength.

Acute and Chronic Injuries with Poor-Quality Tissue

- If poor-quality tissue is identified at the time of repair secondary to preexistent tendinosis, failure of previous repair, or traumatic defect, soft tissue should be supplemented with allograft or autogenous tissue.5, 6

- For acute injuries, the most common cause of poor-quality tissue is preexistent patellar tendinosis. If this is less than one third of the tendon width, primary repair alone is usually adequate. If more tissue is involved and primary repair would cause a patella baja, then autogenous supplementation with hamstring tissue is most common (Fig. 28-3).

- A transverse drill hole at the level of the tibial tubercle and across the middle to distal portion of the patella is most common and allows supplementation with two strands in a longitudinal or figure-eight fashion.6 In contrast, we have created a central vertical tunnel through the patella to augment and to pass the tissue through and then loop it back onto itself. The benefit of this technique is that the site of the tendinosis is usually central, not medial or lateral.

- In cases with extensive patellar tendon tissue loss, Achilles’ tendon allograft can be used (Fig. 28-4).5 The graft is fixed distally in a bone trough and split into three strands. The central strand is passed through a vertical transpatellar tunnel, and the medial and lateral strands are wrapped on either side and the strands repaired side to side. Special care should be emphasized to optimize patella height by comparing to the opposite knee and obtaining intraoperative radiographs.

Figure 28-2 Acute repair of longitudinal intrasubstance tears of the patellar tendon with proximal and distal limbs.

Figure 28-3 Augmentation of patellar tendon repair with semitendinosus tendon (St). G, gracilis.

Figure 28-4 Allograft reconstruction of chronic or patellar tendon ruptures with extensive soft tissue loss.

- In chronic ruptures, proximal scar tissue release and quadriceps tendon lengthening may be necessary to regain normal patellar height. An external fixation traction apparatus has been applied in rare cases to bring the patella down, but pin site infections have been problematic.

Rehabilitation

- Postoperative rehabilitation depends on the quality of tissue, quality of repair, and strength of the suture or fixation apparatus.

- Classic rehabilitation involves the use of a cylinder cast for 6 weeks.1, 2, 7 The patient is allowed to bear weight as tolerated with crutches in the cast. After 6 weeks the patient is converted to a control-dial hinged knee brace. The brace begins at 0 to 40 degrees and advanced 10 degrees per week over the next 6 weeks. Progressive quadriceps and hamstring strengthening and gait training are also performed in the second 6 weeks. When the patient has adequate quadriceps function and 90 degrees of motion, the brace is discontinued. Resistive strengthening and continued range-of-motion activities may take an additional 2 to 3 months.

- Several authors have used early, protected range of motion without cast immobilization in repairs performed both with and without augmentation. They argue that early range of motion reduces the risk of stiffness and the need for secondary manipulation. In limited populations this appears to be a potential alternative to the classic rehabilitation of patellar tendon repair.

- Our current preference is early, protected range of motion in a hinged knee brace. The knee is locked in extension for weight bearing but unlocked three to four times per day with the patient lying prone to begin range-of-motion activities. This allows gravity assist to the quads and reduces forces across the repair. For the first few weeks only 0 to 30 degrees of motion is allowed, with the thought that this improves joint lubrication of the patellofemoral joint and tibiofemoral joint. After 3 weeks, the range is advanced 10 degrees per week, with the patient accomplishing 0 to 90 degrees of motion by 6 weeks. It should be noted that this program can be performed only with excellent suture technique, strong suture, a cooperative patient, and an appropriate injury pattern. Midsubstance tears or poor-quality tissue is treated with a more conservative plan of rehabilitation.

References

1 Caborn DNM, Boyd DW. Tendon ruptures. In Fu FH, Harner CD, Vince KG, eds. Knee Surgery. Philadelphia: Williams and Wilkins; 1994: 911–925

2 Scuderi GR. Quadriceps and patellar tendon disruptions. In Scott WN ed. The Knee. St. Louis: Mosby-Year Book; 1994: 469–478

3 Chen CH, Niu CC, Yang WE, et al. Spontaneous bilateral patellar tendon rupture in primary hyperthyroidism. Orthopedics 1999;22:1177–1178

4 Van Glabbeek F, De Groof E, Boghemans J. Bilateral patellar tendon rupture: case report and literature review. J Trauma 1992;33:790–792

5 Falconiero RP, Pallis MP. Chronic rupture of a patellar tendon: a technique for reconstruction with Achilles allograft. Arthroscopy 1996;12:623–626

6 Larson RV, Simonian PT. Semitendinosis augmentation of acute patellar tendon repair with immediate mobilization. Am J Sports Med 1995;23:82–86

7 Enad JG, Loomis LL. Patellar tendon repair: postoperative treatment. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2000;81:786–788

< div class='tao-gold-member'>