Actual Evidence in the Literature

Many therapies are proposed in LBP management in everyday clinical practice. For some therapies there are no data at all or limited evidence at best Occasionally, the only rationale of prescription is traditional, while for others we can rely on more consistent findings. We distinguish the treatment options as PO treatments (oral drugs and injections, physical therapies, manipulations), FO approaches, and educational interventions (

9). This distinction could now appear to some readers less than totally justified: in fact, most of the PO approaches propose themselves as “normalizers” of physiology and/or “aetiological” (

34,

61,

92,

93,

94,

95,

96), but to date there are no scientific proofs of these hypotheses. Moreover, according to the actual literature we will consider together ALBP and SALBP because there are not enough papers to make a real distinction between the two.

Exercises

The use of exercises as a therapeutic tool for LBP is quite common in most countries of the West (

120), despite scientific evidence that shows its efficacy to be quite inconsistent. In a 2000 Cochrane review, the authors highlight the modest effectiveness of exercises in treatment for patients with CLBP while noting its effectiveness in reducing work absenteeism in patients with SALBP. In ALBP, the benefits of exercises are considered to be as effective as conservative treatment or nontreatment (

110).

The low effectiveness of exercises, as reported in a great number of studies published in scientific journals, is in contrast to the benefits perceived by patients and experts in the treatment of LBP. This discrepancy may be due to the fact that in a great number of these studies with high scientific impact the subjects are randomly chosen and placed in various treatment groups without being first classified into subgroups based on the criteria of pain characteristics (

121,

122,

123,

124). Such a method, being conceptually flawed from the outset, can skew the outcome of clinical trial results. Because classification based on a proposed relevant pathology is possible in at least 10% of cases (

125), one of the objectives of a diagnostic procedure would be to allow the collection of data useful in placing subjects in homogeneous groups in order to prescribe the most appropriate treatment (

121). If it is not possible to classify according to etiology, presumably it will be possible for functional characteristics, or others that are now under scientific exploration. Until then, we have to wait before being able to state clearly what the evidence on exercises can be.

Moreover, this may explain why various types of exercise— albeit with very different physiological origins—have all shown benefits in treating LBP, particularly CLBP (

110,

120,

126).

A few years ago, an open question in the treatment of patients with LBP was to explore whether trunk-flexion exercises would be more efficient than trunk-extension exercises. Studies did not completely resolve this question because the choice of prescribing a preferred course of exercises could not be entrusted to randomness but instead through a careful examination of subjects based on the characteristics of the symptom and its modification (

62). Recently, an in-depth meta-analytical study examined precisely the types of exercises that were potentially the most effective in the treatment of CLBP (

110,

120,

126). While promising results emerged from the study, both in the area of muscle stretching and strengthening, its main conclusion was that much more research would be needed before a better definition of protocols could be reached, and that the best course is most likely that of subclassifying patients.

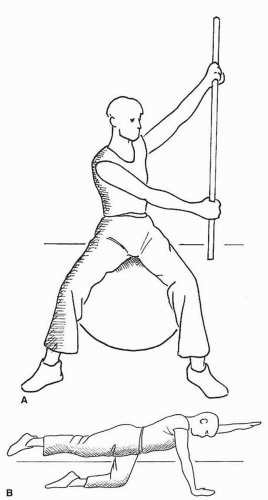

The objectives of exercise (

Fig. 33-3) could include:

Reducing the sensation of pain could be linked to biological changes in tissues, thanks to increased blood circulation, improved mechanics of the joints in question due to the stimulation of joint capsules and their ligaments, better function of stabilizer muscles, and a neurological de-sensitization of tissues, thanks to the repetition of movement (

127).

In SALBP and CLBP, along with pain the patient must also face various other problems. Many studies have shown that “pain-related fear” has a negative impact on some basic spinal functions, such as elasticity and strength (

128). This condition increases the risk of a progressive worsening of disability and the development of a deconditioning syndrome, which could be an additional obstacle to improving conditions. Another typical behavior is that a CLBP patient may exhibit “avoidance behavior”: The patient fears incurring back damage and adopts motor behavior marked by excessive caution (

129), which further worsens motor neurological quality. An intensive, targeted exercise program could reduce the risk of kinesiophobia and have a positive impact on the related disability (

130,

131). In this respect, there are proofs that a graded increased functional training has good results in SALBP (

132,

133,

134), but this methodology can quite easily be extended to CLBP patients (

110,

120) allowing to achieve cognitive-behaviorals goals as well (

111).

There are many studies that have shown how the characteristics of the muscles that maintain the stability of the spine change after an episode of LBP. The lumbar multifidus muscle exhibits a delayed activation (

135) and a decrease in the transversal size on the side of the pain (

136). It has been observed notably that in the absence of specific treatment these deficits remain, even when the LBP disappears. The high incidence of recurrence in LBP the year after the first episode could be due to precisely this functional weakness in the stabilizer muscles. Some studies have supported this hypothesis by showing how a program of functional reactivation of these muscles could work as a safeguard against future episodes. A year after an episode, a group of subjects who had participated in a specific program for strengthening the lumbar multifidus muscle had a 30% rate of relapse compared to 84% in the group of patients who had not participated. Even a follow-up three years later revealed a significant difference in the results, with a 35% rate of relapse in the group tested compared to 75% in the control group (

137).

The same results were observed for adolescent LBP (

138,

139). The choice of favoring a program of stabilizing exercises to prevent the relapse of LBP is not clearly supported by scientific literature. In the case of recurrent nonspecific LBP, a program of general exercise reduces disability more effectively than a program centered on stabilizing the spine, which should only be an option for cases having obvious signs of instability.

Finally, the so-called functional rehabilitation approach is discussed (

41,

118,

140,

141). This gained popularity in the recent past and has been proposed as an inpatient intensive training of 3 to 5 weeks (

142,

143) or as a long-term training program, mainly machine-guided outpatient training (

67,

119,

144). The main theory at the basis of this approach is derived from sports medicine (

141) and considers function more than pain: in fact results are best in the functionaldisability domains than on the pain itself that is in any case decreased (

41). Even without considering that any kind of rehabilitation by definition must be “functional” (

22), this approach has shown good results (

41) and must be adopted as a concept, even if other settings (i.e., outpatient without specific machines) can be considered apart from the ones presented in the literature.

Cognitive Behavioral Approach

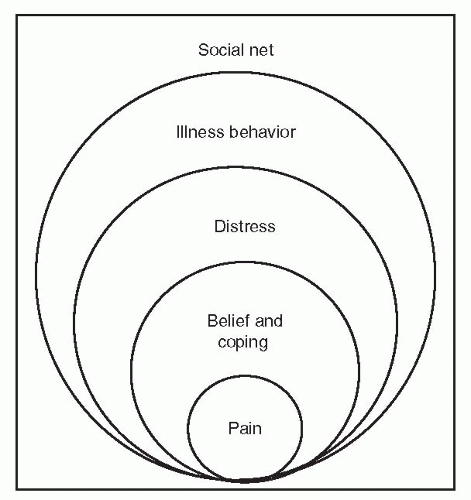

Cognitive-behavioral intervention is commonly used in the treatment of disabling CLBP, and it originates from a new viewpoint in regard to chronic pain. The traditional medical approach considers pain as a cause of illness and consequent disability according to an established illness model (

4,

12). This provides a circle in which physical damage causes pain that will eventually cause impairment, and the impairment will ultimately induce a disability. Nevertheless, while acute pain has a biologic means of alarm to signal tissue damage, chronic pain lacks this characteristic; it is not only influenced by somatic pathology but also by psychological and social factors (

44). Moving from this consideration, Waddel (

Fig. 33-4) theorized a new model of illness for LBP, known as biopsychosocial model, in which various aspects can determine and explain chronic pain. They are:

Physical dysfunction: It depends on an imbalance between the demands of physical ability and real body capacities that are not ready to provide the required performances.

Belief and coping: Human thought and the way of perceiving pain play a crucial role in determining how the patient manages his health problem. Frequently, patients with CLBP are persuaded that they suffer from a serious pathology and are therefore hardly considered curable. They have incorrect assumptions about the possibility of recovery, often due to previous failed treatment. This leads them to adopt a discouraged approach to the problem and to new proposed treatments. The different strategy for coping with pain can explain why certain patients overcome the acute phase, while others come to suffer from CLBP. There are two means of response to pain: actively face it (copers), or undergo it (noncopers). Pain-related fear, catastrophizing beliefs, and lack of psychological and cognitive instruments with which to oppose painful symptoms lead the patient to assume an avoidance behavior from the same pain. This means the reduction of physical activity, work, and social relationships until one arrives at a physical and psychological deconditioning.

Distress: Increased pain perception, emotional stimulus, psychological factors are deeply linked, and they can give rise to a vicious circle. Feelings of fear, anxiety, anger, and depression are common in patients of this kind.

Illness behavior: It is heavily conditioned from prejudices about the pathology, future treatments, and the ability of medical care to resolve the pain.

Social relationship: Social networks such as family, friends, and colleagues can influence the emotional status, development of illness beliefs, and coping strategy. A favorable family activity can help to face and overcome pain, while an accommodating ground to illness will increase it. This model provides a multidisciplinary approach to the problem that requires, above all, a multidisciplinary treatment through the use of different techniques appropriate for the individual subject, such as his or her psychological state.

Two systematic Cochrane reviews (

42,

111) and additional trials (

132,

133,

145), all of which are considered high quality studies, showed there is strong evidence that behavioral treatment is more effective for pain, functional status, and behavioral outcomes than placebo, no treatment, and waiting-list control, most of all when it is intensive, and that a graded activity program using a behavioral approach is more effective

than traditional care for returning to work. One low-quality trial (

146) found there is no difference between the effects of behavioral therapy and exercise therapy in terms of pain, functional status, or depression for as long as a year after treatment.

The goal of the cognitive-behavioral approach to nonspecific CLBP is the ability to modify wrong beliefs about health status and changing the perception of health. Weisenberg (

147) and Meichenbaum (

148), who in 1977 first introduced this model, support the importance of change in the health pattern by a cognitive incentive, seeking to modify the patient’s relationship with the chronic pain by offering him/her the possibility of reacting to pain through an awareness of the real problem. This approach must be presented to the patient like a process of correct learning (

14,

30), in the passage from an illness behavior to a wellness behavior. Generally, three behavioral treatment approaches can be distinguished (

149,

150):

Operant treatment, which is based on the operant conditioning principles of Skinner (

151) and applied to pain by Fordyce (

152) consists of the positive reinforcement of healthy behaviors;

Cognitive treatment, which aims to identify and modify the patient’s cognitions regarding his/her pain and disability;

Respondent treatment, which aims to modify the physiological response system directly.

The first therapeutic aim is to forecast the positive effects of treatment results by acting on external events. This approach allows the patient to move from a control pain model, typical of the acute phase while improving behavioral and functional ability through communication, education, and motivation, which are methodological instruments peculiar to the cognitive-behavioral model. Communication must be efficacious and bidirectional in order to educate the patient in viewing his health condition from the correct perspective. Physicians and therapists should ensure that the patient understands his/her problem and that they are ready to help. Only in this way they can gain the patient’s confidence, which is necessary to ensure good compliance with the treatment. The advantage of the educational program is to offer the patient explanations about the true extent of the problem through easy lessons about anatomy and physiology until the patient can be clearly informed in regard to CLBP. It is useful to encourage the patient to manage his/her pain instead of simply suffering, and giving him/her simple means to be applied in his/her everyday life. This is done by explaining how this active approach to LBP influences, in a crucial way, the perception of pain and the disability correlated to it. This does not signify the minimization of the problem, but instead it helps the patient face it, rid himself from incorrect beliefs and the behaviors of pain avoidance that only serve to strengthen the pain.

The methodology applied is not simply “learn to change” but also “test the change.” To follow this model it is necessary to establish, before treatment begins, certain realistic aims, and to document the improvements through self-evaluation techniques for involving the patient so that he/she will be responsible for the change. The operating setup of this theoretical warning is to test during daily living what the patient learns and to make him/her aware of improvements. Central to diagnostic evaluation is an understanding of the deep interactions between the physical and psychosocial factors, and how they can support themselves according to a vicious circle, since disability in this kind of patient also means chronic pain, physical dysfunction, and illness behavior.

Educational Tools

A primary objective of LBP management is to provide the patient with accurate information. LBP treatment strategies have changed through the past few decades, thanks to the results of various clinical trials conducted during this period. An emblematic example of this is the general consensus regarding the recommendation of remaining active as much as possible during cases of ALBP (

153). However, while it is an important element of LBP primary care, this consensus is not a widely held belief and many people continue to believe their patients need rest.

Accordingly, an updated collection of data to adequately address the issue is an important tool in modifying popular beliefs. In the case of ALBP, it is crucial to reassure the patient and inform him or her of the appropriate methods for managing symptoms (

106). In the case of SALBP, the information must be particularly targeted toward the prevention of chronicity by providing the patient with useful advice on how to identify any behavior that could delay healing (

106). As for CLBP, the information should include advice on how to manage pain, control catastrophism, and decrease avoidance behavior (

106,

111).

Certainly, an informational brochure is the most common educational tool (

154,

155). Many experiments have been carried out to quantify the brochure’s tangible effectiveness in changing common perceptions among patients, modifying behavior, and having an impact on pain and disability. For ALBP patients, the information contained in a brochure seems to be quite effective in reducing pain and the likelihood of relapse (

156), as well as in decreasing fear-avoidance behavior (

154). The brochure has also been used among the institutionalized elderly, and has shown a positive impact on improving disability in the 6 months following its use (

157).

Back schools have been proposed in the past as a possible important tool for LBP treatment (

106,

109), and for a period of time they were quite popular. However, they have been widely criticized (

158) because the original proposals (

159,

160,

161,

162) were mainly based on ergonomic assumptions and a disease-oriented model of illness that was clearly overcome by the actual biopsychosocial one. Nevertheless, the back school can be considered a therapeutic tool that can be filled with the most actual contents and/or according to the individual needs and/or clinical realities, more than a schematically uniform treatment. In everyday clinics this is the reality, because there are as many back schools as there are therapists applying them. Today there are some proofs of

efficacy, mainly in specific professional settings (

109). As a therapeutic tool, if it is used as a cognitive behavioral exercisebased group approach to nonspecific SALBP and/or CLBP, the back school can be important as a low-cost approach to large numbers of patients (

9).

Media is another interesting information tool for educational purposes. With a multimedia information campaign, a significant change can be observed in popular beliefs, with a considerable number of people abandoning the notion that they need rest when experiencing pain and instead embracing the correct idea of remaining active (

163). This change in behavior is cost-effective and continues for several years after the end of the information campaign (

25).

Lastly, various studies have shown that a crucial element in reducing the cost of LBP primary care management is the awareness of getting family physicians to adopt the right behavior (

164), in which a multimedia campaign could play a part.