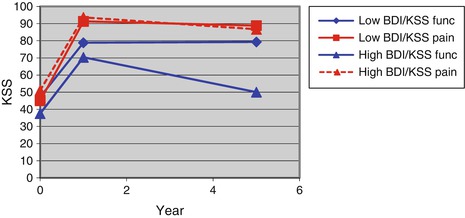

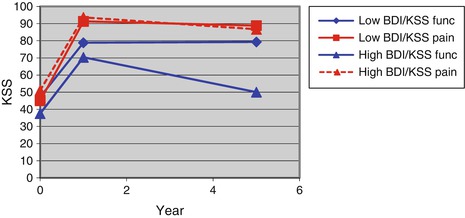

But do these patients with heightened pain at 1 year have persistent disabling pain? Are the associations between preoperative pain, anxiety, and depressive symptoms valid in the long term? In our second study, we asked whether these outcomes persisted over time and whether patients with unexplained heightened pain early after surgery were ultimately satisfied. We prospectively followed 83 patients (109 TKRs) from the prior study 5 years postoperatively. We found that preoperative pain and depressive symptoms predicted lower Knee Society Score at 5 years, but mostly related to lower function subscores (Table 22.2). Although anxiety was associated with greater pain, worse function, and more use of resources in the first year after surgery, anxiety did not affect ultimate outcome. We found that depressive symptoms were consistently associated with long-term outcomes. Our analysis concluded that the Knee Society Score was influenced by psychological variables and therefore was not solely reflective of issues related to the knee [15].

Table 22.2

Elevated Beck Depression Inventory predicted lower function up to 5 years after surgery [15]

In a subsequent study, Hirschmann and colleagues confirmed and expanded upon these findings. They performed a prospective, longitudinal study of 104 patients undergoing TKR, looking at the role of depressive symptoms (Beck Depression Inventory), anxiety (State-Trait Anxiety Index), control beliefs, and other psychological factors on 6-week, 4-month, and 1-year outcomes (Knee Society Clinical Rating System and WOMAC) [16]. They concluded that depressive symptoms, somatization, and psychological distress were all significant predictors of poorer clinical outcome before and after TKR. They did not find that self-efficacy influenced clinical scores.

Other authors have come to similar conclusions regarding mental wellness and TKR outcome. Ayers and coauthors evaluated the relationship between preoperative physical and mental health and function 12 months after TKR. The authors looked at the difference in WOMAC physical function change score between 165 patients with a low and high preoperative mental health. They found that poorer presurgical knee replacement emotional health (SF-36 mental health score) was associated with smaller improvements in SF-36 physical component score and WOMAC Index at 12 months. There was no relationship between the presence of coexisting medical diagnoses and 12-month physical function [17].

Lingard and colleagues investigated the impact of preoperative psychological distress on 3-, 12-, and 24-month WOMAC pain and function scores in 952 patients in 13 centers following knee replacement. Patients completed the WOMAC and SF-36 questionnaires. They dichotomized patients into groups with and without psychological distress. These investigators reported that psychological distress was found to predict pain and function at all time points. WOMAC pain scores for psychologically distressed patients were 3–5 points lower, depending on the time frame, than the scores for the non-distressed patients, after adjustment for covariates. WOMAC function scores did not differ significantly between the two groups following surgery. The changes in the WOMAC pain and function scores for the psychologically distressed patients were not significantly different from those for the non-distressed patients. They concluded that patients with psychological distress demonstrated a substantial decrease in that distress following surgery. Patients who were distressed had slightly worse pain preoperatively and for up to 2 years following TKR [18].

Vissers and associates recently published a systematic review of the studies that looked at psychological factors influencing the outcome of total knee and hip arthroplasty. Thirty-five studies met the inclusion criteria and were included. In follow-ups shorter than 1 year, and for knee patients only, strong evidence was found that patients with pain catastrophizing reported more pain postoperatively. Furthermore, preoperative depression had no influence on postoperative functioning. In long-term follow-up, 1 year after TKR, strong evidence was found that lower preoperative mental health (measured with the SF-12 or SF-36) was associated with lower scores on function and pain. For THA, only limited, conflicting, or no evidence was found. These authors concluded that on the basis of available evidence, low preoperative mental health and pain catastrophizing appear to have an influence on outcome after TKR. With regard to the influence of other psychological factors and for hip patients, only limited, conflicting, or no evidence was found [19].

22.2.3 Gender

Women seem to wait longer for TKR than men. In a study of 95 men and 126 women awaiting knee replacement, Petterson and coinvestigators looked at a variety of health and physical outcome tests (including performance tests, Timed Up and Go, stair climb tests, 6 min walk distance, quadriceps strength). Women had less strength, slower stair climbing and walking, and slower Timed Up and Go. The authors believe that these strength and functional deficits suggest women wait longer and are more disabled when they go to surgery [20].

The relationship of gender and knee replacement outcome is debated [21]. However, a recent study suggests that women recover more quickly than men, but men catch up within a year [22]. Liebs and colleagues utilized a retrospective, cohort design to analyze data from three German prospective multicenter trials that were looking at rehabilitation methods in 494 patients – 141 men and 353 women. Women were on average 3 years older than men at the time of surgery and were physically more limited and in greater pain than men. At the 3-, 6-, 12-, and 24-month follow-ups, men and women had similar WOMAC scores. Improvements were greater for women compared with men for WOMAC function and pain subscale scores at the 3- and 6-month follow-ups. At the 12- and 24-month, there were no differences in improvement between men and women. In summary, although women had greater functional limitations at the time of surgery than men, they recovered faster. There was no difference in long-term outcome. The authors concluded: “We do not know yet why women recover faster from surgery than men. It could be because of women’s lower preoperative health-related quality of life, whereby they have more to gain from surgery, or because of other speculative factors such as different postoperative activity levels, psychological factors, or different utilization of treatment. It is too early to say.”

Kennedy et al. also examined the impact of patient-specific factors, such as gender in THR and TKR patients’ self-report and physical function. They evaluated the results of functional tests (such as the Timed Up and Go test, stair climbing, etc.), perceived VAS pain, and a self-administered questionnaire (LEAP). Women reported greater difficulty and less satisfaction on the leap subscales and greater disability in terms of self-reported and physical performance measures [23].

Osteoarthritic women are probably more likely to express their pain and exhibit more pain behaviors. Keefe and colleagues evaluated 168 subjects (72 men and 96 women) using a variety of arthritis, pain, and mental health measures and performed a 10 min standardized observational session to assess pain behaviors. Women exhibited significantly more pain behavior during the interview and reported higher pain and greater disability. However, when catastrophizing was entered into the analysis, it eliminated the gender differences, even when controlling for depression. Other investigators have also reported that women catastrophize more than men [10].

Are women more hypervigilant to pain? Probably. Social learning models may explain why. The tendency to focus on pain may develop at a young age. When young girls express pain, adult caregivers are more likely to respond with nurturing and attention. Young boys are taught it is not “manly” to express pain. One can speculate other motivations. For example, is it possible that there may be secondary-gain mothers obtain from expressions of pain and the attention it engenders from otherwise distracted adult children or spouses [24]? Speculating on such hypotheses, however, is fraught with error and must be pursued only very carefully, since these can be so compromised by our own biases and experiences. In summary, as a consequence of complex biosocial and psychological reasons, women are more likely to express pain and exhibit pain behaviors. This may be, in large part, a consequence of their greater tendency to catastrophize. However, women come to arthroplasty later and more disabled then men. Fortunately, women appear to recover from surgery faster than their male peers, and ultimately all do equally as well.

22.2.4 Socioeconomic Status and Education

There is evidence that patients from higher socioeconomic groups have higher expectations of joint arthroplasty and that patients with higher expectations have better outcomes [25, 26]. Preoperative function is a strong predictor of postoperative outcome. Patients in lower socioeconomic circumstances, with less education and lower income, appear to have worse arthritic symptoms and greater disability [27]. Therefore, their need is likely more pressing for joint reconstruction [28].

Fortin et al. sought to determine whether patients with knee or hip osteoarthritis who have worse physical function preoperatively achieve a postoperative status that is similar to that of patients with better preoperative function. Education was one of the predictive variables. In addition to the association between preoperative and postoperative disability, they found that a higher education level was associated with better function and less pain 6 months after surgery [29].

In contrast, in a large (974 subjects, 13 centers, 4 countries), prospective observational study, several demographic variables were obtained and then, using multivariate analysis, their association with preoperative and postoperative WOMAC scores described. These authors report that income did not have a significant impact on outcome after adjusting for other covariates. Level of education, as well, did not correlate with preoperative scores or postoperative outcome. The authors conclude “patients with lower incomes appeared able to compensate for their worse pre-operative score and obtain similar outcomes post-operatively. These findings are in contrast to studies on other medical conditions and surgical interventions, in which lower socioeconomic status has been found to have a negative impact on patient outcomes” [28].

22.2.5 Psychological State

There is strong evidence that poor mental health is associated with disability. Depression may be both a consequence of living with chronic joint pain and contributing to the disability that occurs from osteoarthritis. It has been reported that 10 % of people with osteoarthritis are depressed [30] and that psychological symptoms exacerbate pain and disability [31, 32]. People with arthritis are more likely to self- identify as “disabled” compared to those with other chronic conditions [33]. Anxiety in OA is associated with poorer physical function and less frequent accomplishment of specific activities of daily living [32]. In a longitudinal study of coping style, a recent meta-analysis found that dispositional optimism is a significant predictor of positive physical health outcomes across many disease populations [34]. However, other researchers have found that optimism is not strongly related to physical function in patients with knee OA [35]. In a retrospective cohort study of 702 patients, Singh and colleagues reported that pessimists described more pain 2 years after TKR as well as less improvement in knee function that non-pessimists [36]. Hirschmann’s study also reported an association between depressive symptoms and somatization with patients’ clinical outcome before and after TKR [16].

In the other previously described study [13], Riddle and colleagues followed 140 patients undergoing TKR for 6 months. After adjusting for confounding variables, these investigators reported pain catastrophizing was the only consistent psychological predictor of pain. No other psychological predictors were associated consistently with poor WOMAC function outcome [13]. These authors did not find that catastrophizing impacted reported function.

In contrast, Sullivan and colleagues studied whether catastrophizing affects actual physical performance. Healthy undergraduates volunteered to participate in various exercises and then return 2 days later to perform the same tasks. They filled out questionnaires in order to assess catastrophizing before the second round of activities. It was found that catastrophizing was associated with an objectively defined physical force deficit consequent to pain. The authors propose that those who catastrophize will avoid or refuse to perform an activity if he or she believes pain will be experienced [6]. Similarly, Picavet, in a large population study, reported that catastrophizing and kinesiophobia led to increased risk of future lower back pain disability [37].

Self-efficacy is the measure of a person’s belief in his/her competence in succeeding at a task. People with high self-efficacy work harder and longer to achieve their goals. Self-efficacy is proposed to derive from mastery experiences, vicarious experiences, verbal persuasion, and physiological states [38]. Mastery experiences are the most compelling – as they reinforce the individual’s ability to perform the behavior. Vicarious experiences are those in which one compares his activities to others – less compelling but still useful. Verbal persuasion describes learning states. Physiological states, although usually described as a negative (such as increased fatigue) can be positive – for example, increasing quadriceps strength during exercise reinforces the individuals perception he has the capacity to achieve certain goals.

Many investigators have described the relationship between self-efficacy in OA and function, disability, and exercise compliance [39]. Preoperative self-efficacy may improve surgical outcomes as well. One study found that preoperative self-efficacy explained on average 10 % of the outcome variance in self-reported pain, function, and health-related quality of life in TKR patients [40].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree