17

Primary Repair of Posterior Cruciate Ligament Tears

Three zones of the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) have been described.1 Zone 1 is the femoral attachment of the PCL, zone 2 is the middle portion of the PCL between the femoral and tibial attachments, and zone 3 is the tibial attachment of the PCL. Primary repair of PCL tears seems to be best suited for bony avulsions of the tibial attachment (zone 3) or peel-off lesions from the femoral attachment (zone 1).1, 2

Indications

The indications for surgical treatment of acute PCL tears include:

- Insertion site avulsions (bony or soft tissue)

- Proximal tibial stepoff decreased 10 mm or greater

- The multiple ligament injured knee

- PCL tears combined with other structural injuries (meniscus tears and/or articular surface injuries)

Indications for primary repair of the PCL include:

- An acute knee injury with PCL insertion site avulsion in zone 1 (femoral insertion) or zone 3 (tibial insertion site)

- PCL tears in children with an open physis

Contraindications

Contraindication for primary PCL repair is a zone 2 mid-substance PCL tear with interstitial ligament disruption and elongation. Primary repair of zone 2 PCL injuries may be indicated in children with an open physis who are not candidates for PCL reconstruction at the time of their injury.3, 4

Surgical Technique

Prior to repair, the three-zone arthroscopic evaluation of the PCL should be performed to assess the status of the ligament.1 This PCL arthroscopic evaluation visualizes all three zones of the PCL, utilizing a standard 25- or 30-degree arthroscope through the inferior lateral patellar and posteromedial arthroscopic portals. This critical evaluation determines the degree of interstitial disruption to the PCL and whether primary repair or surgical reconstruction is the procedure of choice.

The surgical techniques available for primary PCL repair are open or arthroscopic procedures. Tibial insertion PCL avulsions are repaired using the posterior approach described by Burks and Schaffer5 and Berg.6 The patient is positioned in a supine or lateral position, and a curvilinear posterior skin incision is made. The interval is developed between the medial hamstring tendons and the medial head of the gastrocnemius muscle. The medial head of the gastrocnemius muscle is retracted laterally along with the neurovascular structures. The posterior capsule is incised, exposing the PCL tibial insertion site. The bony bed is curetted of fibrous debris to enhance healing, and the insertion site bed is deepened to allow for countersinking of the ligament attachment to accommodate the potentially unrecognized elongation of the PCL that may have occurred prior to the insertion site avulsion.

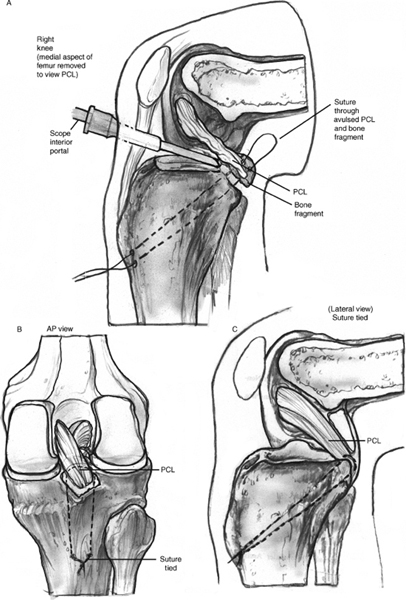

Options for fixation include screw and washer, suture anchors, and transosseous suture or wire fixation. Our preference is to use a fixation device that will not interfere with future PCL reconstructive procedures if the primary repair fails, and to use a device that will not need to be removed. Our preferred fixation device is No. 5 braided permanent suture passed through the ligament/bone piece, and then passed through transtibial drill holes. The suture is tensioned, the PCL avulsion anatomically reduced with a slight countersink, and the suture material tied over an anteromedial tibial bone bridge or ligament fixation button on the anterior medial aspect of the proximal tibia (Fig. 17-1).

Kim et al7 have described the technique of an arthroscopically assisted repair of avulsion fractures of the PCL from the tibial insertion site. This arthroscopic technique utilizes posteromedial, posterolateral, and anterolateral arthroscopic portals. The posterior synovial septum behind the PCL is debrided with a synovial shaver to allow manipulation of the fracture fragment. Care is taken to protect the neurovascular structures. The fracture bed is debrided and the size of the fracture fragment assessed with an arthroscopic probe. Kim et al recommend that fixation methods be determined by fragment size. Large fragments (>20 mm) are secured with cannulated screws. Medium fragments (10 to 20 mm) are secured with multiple pins. Small fragments (<10 mm) without comminution are secured with wire suture, whereas small comminuted fragments are reattached with multiple sutures. The PCL tibial avulsion fragment is reduced and stabilized with a PCL tibial drill guide, and appropriate provisional fixation and/or fixation tunnels are created. Definitive fixation is then achieved based on fragment size, as outlined above. The reader is referred to the original article for details of the surgical procedure.7

Figure 17-1 (A) Line drawing of transtibial sutures laxity from the ligament that may occur due to anchoring a posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) tibial unrecognized elongation. (C) The sutures are tied over a avulsion to its anatomic insertion site. (B) The ligament bone bridge or ligament fixation button on the anterior insertion is slightly countersunk to remove any residual medial aspect of the proximal tibia. AP, anteroposterior.

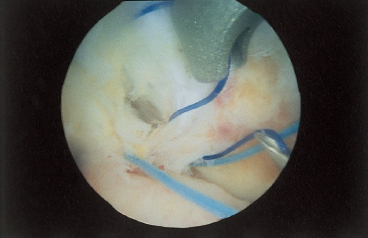

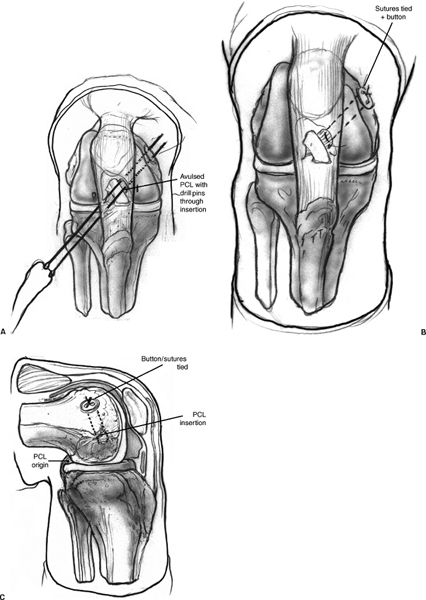

Our preferred method of reduction and fixation of zone 1 (femoral insertion site) PCL avulsions is transosseous suture repair. The bed of attachment at the PCL anatomic femoral insertion site is prepared by debriding as necessary and deepening the attachment site for countersinking. The repair is performed arthroscopically by passing multiple sutures through the avulsed PCL using an arthroscopic suture-passing device (Fig. 17-2). Transosseous drill holes are made using a 3/32-inch Steinmann pin through a low anterolateral arthroscopic portal. The pins are retrieved through a small medial distal femoral condylar skin incision. The sutures are tensioned, anatomically reducing the avulsed PCL in its bed. The sutures are tied over a bone bridge or a ligament fixation button (Fig. 17-3).

Figure 17-2 Photograph of a suture-passing device placing multiple sutures through a PCL femoral peel-off lesion. The sutures are then passed through drill hole(s) made at the anatomic femoral insertion site of the PCL and tied over a bone bridge or a ligament fixation button.

Postoperative Care

The patient is placed in a long leg brace locked in full extension for 6 weeks to allow healing of the repair site. Beginning postoperative week 7, the brace is unlocked, and progressive weight bearing and range of motion are initiated. Strength and proprioceptive training exercises are initiated and progressed, avoiding resisted open kinetic chain hamstring exercises for 6 months. Return to strenuous activity is permitted after 6 months if strength and proprioceptive skills are adequate.

Tips and Tricks

Correct assessment of the degree of PCL damage is critical for the success of primary repair. We recommend the three-zone arthroscopic evaluation of the PCL before performing any PCL primary repair.1 It has been my experience that small flecks of bone associated with tibial insertion-site PCL avulsions have a high incidence of zone 2 (midsubstance) interstitial PCL disruption, making PCL reconstruction the preferred surgical treatment instead of primary repair (Fig. 17-4). Countersinking the insertion site to accommodate potential elongation in a normal-appearing ligament may help to prevent residual laxity.

Avoiding Pitfalls

Pitfalls to be avoided include:

- Failure to recognize interstitial zone 2 damage of the PCL, leading to primary repair failure

- Failure to recognize and treat associated ligament injuries, most commonly posterolateral instability, leading to failure of the PCL repair

- Failure to adequately protect the neurovascular structures during surgery, leading to nerve or blood vessel damage.

Conclusion

The incidence of PCL tears seems to be patient population dependent.8 Isolated PCL tears are relatively rare, and PCL tears combined with posterolateral instability are a common combination.8 Primary repair of PCL injuries seems to be best suited for large bony avulsions (20 mm or greater) from the zone 3 tibial insertion and peel-off lesions from the zone 1 femoral insertion. The three-zone arthroscopic evaluation of the PCL is essential to assess zone 2 prior to primary repair.1 Associated ligament injuries must be recognized and treated. The nerves and vessels of the popliteal fossa must be protected. Primary PCL repair in selected cases has had very successful results.9, 10

Figure 17-3 Line drawing of transfemoral condylar sutures anchoring a PCL femoral insertion site avulsion.(A) The suture passing pins drilled arthroscopically through a low anterolateral portal into the PCL femoral insertion site and retrieved through a small skin incision on the distal medial femoral condylar area. (B, C) The sutures are tensioned, the PCL avulsion reduced, and the sutures tied over a bone bridge or ligament fixation button on the distal medial femoral condyle.

Figure 17-4 Lateral x-ray of a PCL tibial avulsion with a small fragment of bone. Three-zone arthroscopic PCL evaluation of the injured knee revealed severe interstitial damage to the zone 2 midbody of the PCL. The preferred treatment was surgical reconstruction rather than primary repair.

References

1 Fanelli GC, Giannotti BF, Edson CJ. Current concepts review. The posterior cruciate ligament arthroscopic evaluation and treatment. Arthroscopy 1994;10:673–688

2 Harner CD, Hoher J. Current concepts. Evaluation and treatment of posterior cruciate ligament injuries. Am J Sports Med 1998;26:471–482

3 Suprock MD, Rogers VP. Posterior cruciate avulsion. Orthopedics 1990;13:659–662

4 Lobenhoffer P, Lutz W, Bosch U, Krettek C. Case report. Arthroscopic repair of the posterior cruciate ligament in a 3-year-old child. Arthroscopy 1997;13:248–253

5 Burks RT, Schaffer JJ. A simplified approach to the tibial attachment of the posterior cruciate ligament. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1990;254:216–219

6 Berg E. Posterior cruciate ligament tibial inlay reconstruction. Arthroscopy 1995;11:69–76

7 Kim S, Shin S, Choi N, Cho S. Arthroscopically assisted treatment of avulsion of the posterior cruciate ligament from the tibia. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2001;83:698–708

8 Fanelli GC, Edson CJ. PCL injuries in trauma patients: Part II. Arthroscopy 1995;11:526–529

9 Richter M, Kiefer H, Hehl G, Kinzl L. Primary repair for posterior cruciate ligament injuries. An eight year follow-up of fifty-three patients. Am J Sports Med 1996;24:298–305

10 Hughston JC, Bowden JA, Andrews JR, Norwood LA. Acute tears of the posterior cruciate ligament. Results of operative treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1980;62:438–450

< div class='tao-gold-member'>