CHAPTER 101 Postoperative Deformity of the Cervical Spine

Preventing Iatrogenic Cervical Malalignment During Anterior Surgery

Positioning

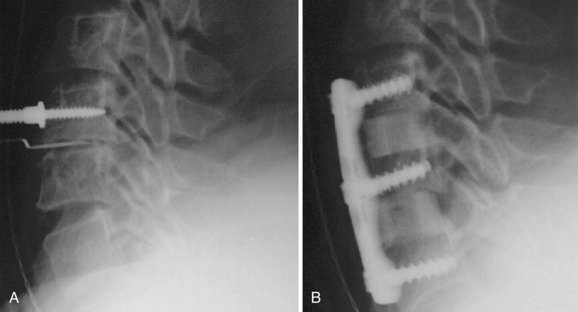

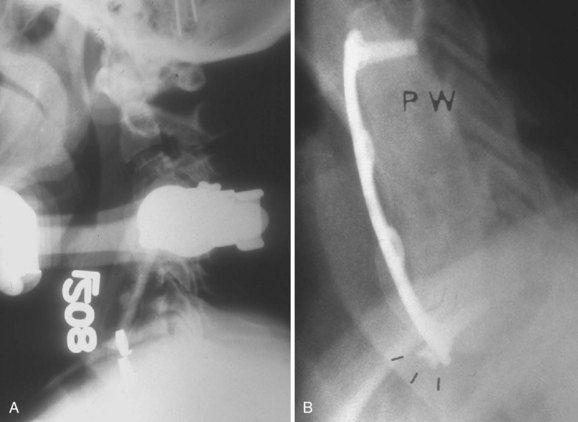

The most common error of patient positioning for anterior surgery is to put the patient’s neck into hyperlordosis. A rolled towel is often placed underneath the patient across the shoulders to extend the neck. Whereas moderate cervical lordosis is desirable, hyperlordosis such that the spinous processes are touching is, in general, excessive. If the patient is fused in this position he or she will often have severe interscapular and posterior cervical pain, especially if an extensive foraminotomy is not performed at the time of the procedure. Extension of the neck narrows the posterior neural foramen and may result in root compression. To avoid this complication, we routinely inspect the position with the patient supine to ensure that the neck is in a relatively neutral or slightly lordotic position. In addition, we examine the localizing radiograph to verify that the neck is in an acceptable amount of lordosis. If the patient’s neck is hyperlordotic on this radiograph, we place Caspar distractor pins with the tips converging. When the distractor is placed over the pins, the amount of lordosis will be reduced (Fig. 101–1). At the end of the procedure, the goal is to have the neck in a normal lordotic configuration.

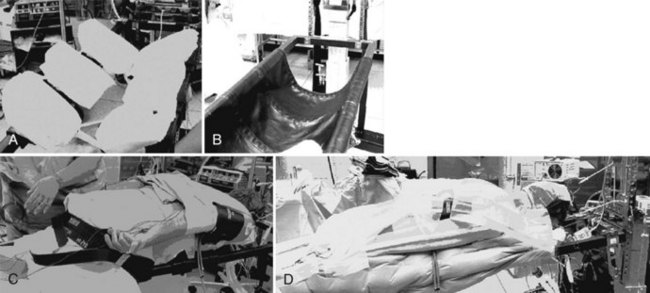

The surgeon can avoid creating a rotational deformity by using one of two techniques. The first is to ask the anesthesiologist to confirm that the nose is pointed straight up before placing any grafts and putting on the instrumentation. This, however, requires that the surgeon remember to ask the anesthesiologist. We prefer to use a more foolproof technique of routinely placing a tape across the forehead to prevent inadvertent rotation of the head during the operation (Fig. 101–2). Another variation on this technique is to use commercially available head holders with an elastic chinstrap to stabilize the head. When one is performing high cervical approaches to C2-3 or C3-4, it is sometimes advantageous to rotate the neck to the contralateral side so as to gain better access to the spine. Under those circumstances, it is a good idea to write a reminder on the sterile drape to turn the head back into neutral alignment before grafting and plating are done.

Decompression

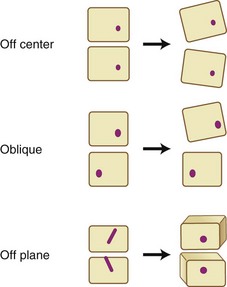

We routinely use Caspar distractor pins to open the disc space during anterior cervical surgery. Although the distractor is quite useful in exposing the disc space, one must be careful in placing the pins. If both pins are placed off center to one side, the disc space will open asymmetrically, causing segmental coronal angulation. If the pins are placed in an oblique position, the disc space will open asymmetrically and relative lateral translation of the vertebral bodies will occur. Finally, if the pins are placed in different planes, a rotational malalignment of the vertebra can occur (Fig. 101–3).

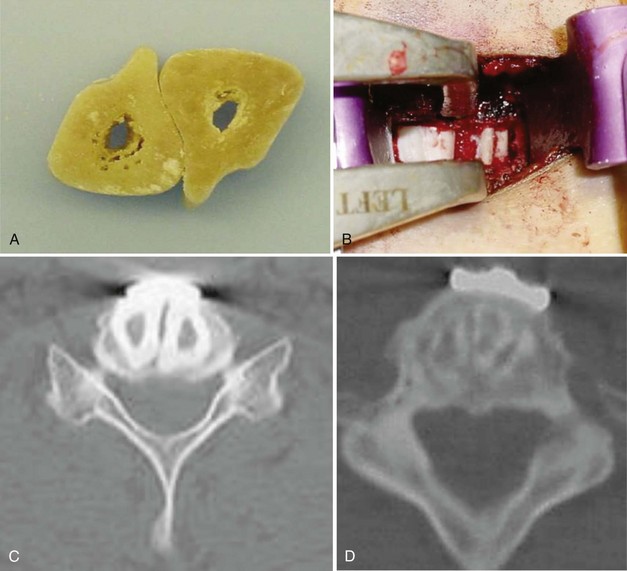

Failure to expose the entire disc space may increase the likelihood of performing an asymmetrical discectomy or corpectomy. Placing a graft asymmetrically on one side may result in a coronal plane deformity (Fig. 101–4). One can avoid this by exposing the intervertebral disc to the uncovertebral joints bilaterally before starting the decompression. These lateral structures provide a fixed reference to the surgeon and assist in performing a symmetrical decompression and reconstruction.

The type of decompression one performs also matters. Long corpectomies reconstructed with an allograft long bone can only be placed into a neutral or kyphotic position; because the graft is straight, it is impossible to produce lordosis. Kyphosis typically develops as the graft subsides into the endplates. To avoid this, we routinely use segmental decompression combining corpectomies at the levels that have retrovertebral compression with discectomies at levels that only have retrodiscal neural compromise (Fig. 101–5). For patients who have retrovertebral compression at more than one level, we perform a procedure that we call corpectomy-corpectomy: performing corpectomy at one level and skipping the next level, followed by a corpectomy at the third level (Fig. 101–6). This type of segmental decompression and fixation using several small grafts rather than one long strut graft allows for better preservation of cervical lordosis.

Noninstrumented Fusion

A multilevel noninstrumented arthrodesis of the cervical spine can result in kyphosis as the grafts collapse or resorb (Fig. 101–7). Whereas the use of a plate does not absolutely guarantee the avoidance of kyphosis, most surgeons would agree that anterior cervical plates decrease the likelihood of postoperative kyphosis.1,2

Graft Selection

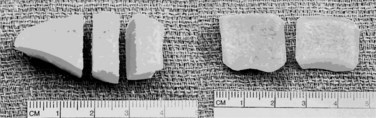

The type of graft material that one uses can also influence the likelihood of postoperative kyphosis. In general, fresh frozen allografts are less likely to collapse than freeze-dried bone, and freeze-dried bone is less likely to collapse than irradiated, freeze-dried bone.3 If a surgeon finds a piece of allograft to be fragile, it is advisable to use another specimen rather than implanting an inferior allograft. We most commonly use cortical allografts harvested from the fibula, ulna, radius, humerus, and occasionally the tibia. We also use dense cancellous allograft from the patella (Fig. 101–8).

The size of the graft also influences the propensity to develop postoperative kyphosis (Fig. 101–9). The grafts should be large enough to allow for 1 or 2 mm of subsidence without creating kyphosis. In addition, the more graft one uses per level, the less likely it is to collapse. For this reason, we routinely fill the disc space with as much graft as possible, which often means placing two allografts side by side (Fig. 101–10).

FIGURE 101–9 This surgeon placed prefabricated grafts that are clearly undersized, resulting in segmental kyphosis.

Anterior Instrumentation

Although judicious and careful use of anterior cervical plates can help avoid postoperative kyphosis, poor attention to detail can result in plate-induced malalignment. If a screw inadvertently perforates an adjacent disc space, it can result in rapid degeneration and collapse of that disc space. Even if the screw does not perforate the next disc space, placement of a plate within 5 mm of an adjacent level increases the likelihood of adjacent-level ossification development (Fig. 101–11).4 The adjacent-level ossification can become quite profound, causing rapid deterioration of that adjacent disc space, and result in kyphosis. The surgeon must be careful not to use a plate that is too long, especially when using dynamic or subsidence plates because these will migrate toward the adjacent disc spaces as the grafts subside.

FIGURE 101–11 If a plate is too close to the neighboring disc space, adjacent-level ossification disease may occur.

Patients who have long corpectomies are prone to graft extrusion. The reported incidence is as high as 9%.5 Unfortunately, plates do not help prevent such complications (Fig. 101–12).6 With static plates, extension of the neck loads the graft as the plate acts as an anterior tension band. In flexion the graft is unloaded because the anterior cervical plate acts as the center of rotation. In extension the inferior screws can pull out, and in flexion they can be driven into the next disc space, resulting in graft collapse or extrusion. To avoid these complications, we routinely perform circumferential stabilization in patients who undergo corpectomies at two or more levels. We also prefer a circumferential approach in patients with poor quality bone who undergo single-level corpectomies.

Preventing Iatrogenic Cervical Malalignment During Posterior Surgery

Positioning

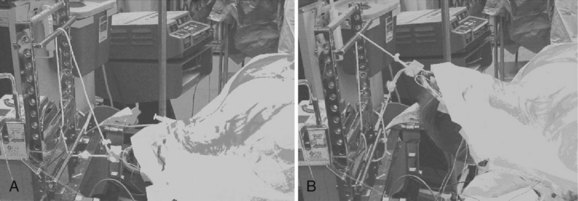

Positioning for posterior cervical procedures is just as critical as for anterior operations. We routinely use the Jackson frame (OSI-Orthopedic Systems, Inc., Union City, Calif.) to position our patients for posterior operations (Fig. 101–13). We tape the shoulders down just as for the anterior procedures. We also make sure that one shoulder is not pulled asymmetrically in order to prevent an iatrogenic coronal plane deformity. We place bolsters just underneath the clavicle and use Gardner-Wells tongs with bivector traction to allow us to position the neck in either flexion or extension (Fig. 101–14). We check the position preoperatively to ensure that we can place the neck into an adequate amount of flexion and extension. Foraminotomies are best accomplished with the neck in maximal flexion, which unshingles the facets and exposes the underlying superior articular facet. If the neck is not adequately flexed during a foraminotomy, one must resect a large amount of the overhanging inferior articular facet to expose the underlying superior facet. This may weaken the structure and lead to a fracture. More commonly, it makes it difficult to place a lateral mass screw in patients who require a fusion and decompression. Before fusion, we change the weight from the lower, or flexion, rope to the upper, or extension, rope. The advantage of using bivector tong traction is that the surgeon can easily alter the position of the neck intraoperatively. With fixed head holders such as Mayfield tongs, an assistant has to crawl under the table to reposition the head holder.

Although it is important to position the neck properly for fixation of the subaxial spine, it becomes even more critical when one is performing an occipitocervical or an occiput-to-thoracic fusion. If the neck is improperly positioned and instrumented, the resulting malalignment can be quite debilitating. Phillips and colleagues7 measured the occipitocervical angle on 30 normal cervical spine radiographs of patients in flexion, extension, and neutral alignment. The occipitocervical angle was defined as the angle between the McRae line (the line connecting the basion and opisthion, which demarcates the foramen magnum on a lateral radiograph) and a line parallel to the rostral endplate of C3. The mean occipitocervical angle on the neutral radiographs was 44 degrees. Phillips and colleagues7 recommend that when performing an occipitocervical fixation and fusion, the surgeon should try to fix the occiput and upper cervical spine in as close to this value as possible to provide the patient with a functional head position (Fig. 101–15). We concur with this for patients with occipitocervical fusions. However, when performing occiput-to-thoracic fusions, we prefer to fix the patient with 5 to 10 degrees of flexion compared with normal. This is because these patients are unable to bend their necks at all, and if they undergo fusion looking straight ahead they cannot look down to see their own bodies.

Decompression

Deformities can result from overly aggressive decompressions of the cervical spine. Even minimally invasive procedures such as posterior cervical foraminotomies can result in a postoperative deformity. If the procedure is performed through a small tubular retractor by a surgeon who is not intimately familiar with the microanatomy of the facet joint or who loses anatomic landmarks, too much of the facet may be resected. Zdeblick demonstrated that resection of more than 50% of a facet can result in instability (Fig. 101–16).8 To prevent this, one must always identify and visualize the lateral and medial aspects of the facet joint and take care to resect only the medial half of the joint.

FIGURE 101–16 Resection of more than 50% of the facet, particularly in the setting of a complete laminectomy, may lead to kyphosis.

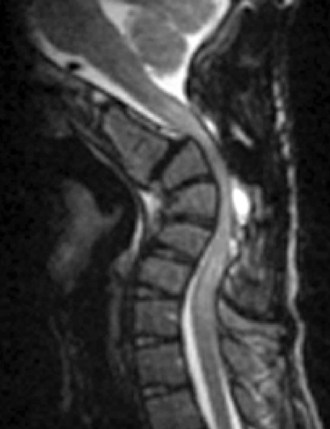

A more common deformity-causing decompression is a laminectomy without a fusion. Laminectomies in children have been associated with a high incidence of postlaminectomy kyphosis (Fig. 101–17).9 Even in adults it is difficult to predict when a patient might develop postoperative kyphosis. We therefore reserve complete laminectomies for patients who have significant anterior-stabilizing osteophytes with minimal range of motion of the cervical spine.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree