Type

Description

1.

Incomplete detachment

2.

Incomplete and concealed avulsion (Kim lesion)

3.

Chondrolabral erosion

4.

Flap tear

Posterior labrocapsular periosteal sleeve avulsion (POLPSA). This lesion is characterized by stripping of the posterior labrum and the intact posterior scapular periosteum from the glenoid; the avulsion creates a redundant recess that communicates with the joint space [15, 16].

Bennett lesion. This is an extra-articular curvilinear calcification along the posterior-inferior glenoid near the attachment of the posterior band of the inferior GH ligament (IGHL) [17]. POLPSA lesions are suspected to be the acute stage of a Bennett lesion [16].

Posterior humeral avulsion of the GH ligament (PHAGL). A PHAGL lesion is one where the posterior IGHL has been avulsed from its humeral attachment.

Floating PHAGL. This very rare condition is a combination of a PHAGL and a reverse Bankart lesion.

Stretched posterior capsule. Recurrent subluxations or dislocations can stretch the capsule, giving rise to a pathological posterior-inferior capsular pouch. The excessive capsular laxity and the capsular recess may be the primary lesion in patients with atraumatic instability [18].

Accompanying lesions including SLAP tears, superior GH ligament tear and medial GH ligament, and an enlarged axillary pouch are found in patients with posterior shoulder instability [19].

21.2 Mechanism of Injury

The causes of posterior instability range from acute traumatic injury to repetitive microtrauma and a nontraumatic etiology [5, 20, 21]. Treatment requires correct identification of pathogenesis.

Repeated microtrauma to the posterior structures of the shoulder induced by repetitive bench press lifting, overhead weight lifting, rowing, swimming, playing as blocking lineman in football, and all sport activities involving a load borne in front of the body are the most frequent causes of posterior instability. In overhead athletes loading of the shoulder in flexion and IR causes stretch and injury of the posterior IGHL and posterior-inferior joint structures. This induce a progressive posterior laxity. Patients seldom remember a particular movement or situation that caused the symptoms.

Acute traumatic posterior dislocation commonly involves a direct load on the flexed and internally rotated shoulder. It is typically related to a high-energy trauma (e.g., motorcycle accident), electrocution, seizure, or high-weight bench press exercises. A nontraumatic pathogenesis is rare. Patients with generalized ligamentous laxity are predisposed to posterior instability [14].

21.3 Clinical Examination

Patients with posterior instability usually report general shoulder pain or pain deep in the posterior aspect of the shoulder [22, 23]. The pain can be associated with loss of strength and decreased athletic performances, such as reduced bench press capacity or inability to do the same number of push-ups [5, 24, 25]. In these nonspecific conditions, it is important to avoid confusing posterior instability with outlet impingement, biceps injuries, or myofascial disorders.

A common finding in patients with posterior instability is impaired scapulothoracic mechanics, due to rotator cuff imbalance which is related especially to the subscapularis.

Some patients can subluxate their shoulder voluntarily. This is a complex therapeutic situation where it is crucial to differentiate voluntary positional instability from voluntary muscular instability [23]. The former condition consists of subluxation in a provocative position; these subjects are not gratified by their ability to subluxate the shoulder, unlike those with willful voluntary instability, who have learned to subluxate their shoulder and do it habitually. Voluntary muscular instability is non-position-dependent and suggests ligamentous laxity or muscle imbalance and should not be considered as a form of true posterior instability.

Clinical examination plays a crucial role in the diagnosis of posterior instability. The patient usually reports nonspecific symptoms and the condition is often misdiagnosed. As in all instances both shoulders need to be evaluated for appearance, motion, muscle tropism, muscle strength, scapular tracking, and neurovascular status, including the axillary nerve, to elicit symptoms of posterior instability.

Range of motion (ROM) is often normal and symmetric [21]. Some patients may present increased external rotation (ER) and a slight loss of internal rotation (IR).

A number of specialized tests are especially useful for a correct diagnosis:

Apprehension test: an axial load is applied to the flexed, adducted, and internally rotated shoulder [21]. The test is positive if the patient experiences pain and a feeling of instability.

Jerk test: the examiner standing next to the affected shoulder holds the elbow in one hand and the distal clavicle and scapular spine in the other. The arm is flexed and internally rotated. The examiner pushes the flexed elbow posteriorly and the shoulder girdle anteriorly (Fig. 21.1). The test is positive if a sudden jerk associated with pain occurs as the subluxated humeral head relocates in the glenoid fossa [26].

Fig. 21.1

Jerk test: the patient is standing, the arm is flexed and internally rotated, and the examiner pushes the flexed elbow posteriorly and the shoulder girdle anteriorly. The test is positive if a sudden jerk associated with pain occurs

Kim test: it is performed with the patient seated and the arm in 90° of abduction. An axial load is applied and the arm is slowly brought in forward elevation (Fig. 21.2). The test is positive if the patient experiences pain and a posterior subluxation [27].

Fig. 21.2

Kim test: An axial load is applied on the arm in 90° of abduction and slowly brought in forward elevation (white arrows). The test is positive if the patient experiences pain and a posterior subluxation

A combination of positive Kim and jerk tests has 97 % sensitivity for posterior instability [27].

Posterior stress test: with the patient seated, the examiner stabilizes the medial border of the scapula and applies a posterior force with the arm in 90° forward flexion, adduction, and IR. The test is positive if the shoulder subluxates or dislocates with pain and/or apprehension.

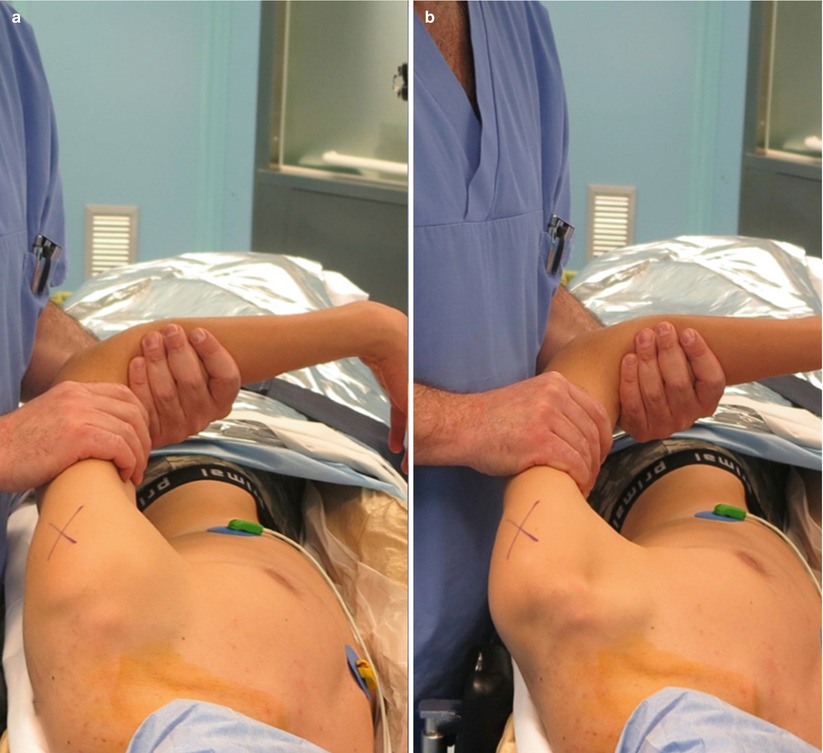

Load and shift test: with the patient supine and the arm in forward flexion and abduction, the humeral head is loaded while anterior and posterior stresses are applied (Fig. 21.3a, b). Excessive inferior translation of the humerus on the glenoid is often associated with posterior subluxation [22].

Fig. 21.3

(a, b) Load and shift test: the arm is placed in slight flexion and abduction (20°); the humeral head is loaded while anterior and posterior stresses are applied

21.4 Diagnostic Imaging

Diagnostic imaging is crucial to detect direct and indirect signs of posterior instability.

Plain radiographs including an anterior-posterior view, a true anterior-posterior view (Grashey view), a scapular (Y) lateral view, and, especially, an axillary lateral view provide essential information about glenoid and humeral head morphology and the presence of any bone defects.

CT scans are useful to evaluate bony morphology, particularly small bony defects or fractures such as reverse bony Bankart lesions. Three-dimensional reconstructions are very useful for preoperative planning. CT is endowed with 86.7 % sensitivity and 83.3 % specificity for posterior glenoid bone loss [29].

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and arthrography (MRA) accurately detect soft tissue injuries, in particular capsule lesions and partial or complete labral tears (Fig. 21.4). MRA is highly sensitive and specific for labral tears (91.9 and 96 %, respectively), SLAP lesions (89 and 93.8 %, respectively), and Hill-Sachs fractures (93.3 % accuracy) [30].

Fig. 21.4

Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance (MR) of the left shoulder depicting a posterior labral detachment (white arrow) in a professional volleyball player

21.5 Treatment Strategy

The treatment of posterior instability in athletes depends on symptom severity, including pain intensity, degree of impairment of athletic performance, and pathological features of the joint lesion. All athletes should be encouraged to undertake conservative treatment including physical therapy and rehabilitation as an initial approach [20, 31]. An appropriate program of strengthening and proprioception exercises can reduce pain and improve stability in most cases of posterior and multidirectional instability [20, 31]. Subjects with ligamentous laxity and repetitive microtrauma may benefit from physical therapy [21], whereas conservative treatment is less successful in patients with a history of shoulder joint trauma [20, 21, 31]. To our knowledge there is no evidence in the literature for the ability of braces or orthoses to prevent recurrence during games/matches.

Patients with clear symptomatic posterior labral injury rarely respond to conservative treatment and are therefore candidates for surgical management [14, 32]. If nonoperative treatment fails to restore joint stability and reduce pain during sport activities, surgery followed by an appropriate postoperative rehabilitation program is recommended. Voluntary posterior dislocation is a contraindication for surgical stabilization [33], even though arthroscopic stabilization seems to afford satisfactory outcomes [34]. Voluntary or posterior instability is not uncommon in professional swimmers and gymnasts, who have multi-joint capsule and ligament laxity [35]. Some of these patients may move from posterior positional to voluntary instability; in positional instability the humeral head subluxates posteriorly when the arm is abducted over 90° and relocates spontaneously when the arm returns along the side [33].

In our view management of posterior instability includes nonoperative treatment for at least 6 months for in-season athletes who complain of pain and a moderate feeling of instability but can tolerate training and competition. Considering that most of these athletes complain of pain and subluxation rather than complete dislocation, we recommend postponing surgery after the season, when postoperative rehabilitation and shoulder training programs are easier to follow. This strategy is consistent with methods described by other colleagues [36] and is the result of a 20-year experience in shoulder and elbow surgery.

21.6 Operative Technique

Although open surgery has been the procedure of choice for many years (deltoid split, release of the interval between infraspinatus and teres minor to incise the capsule and expose the posterior labrum) [37], most surgical procedures are now performed arthroscopically with similar outcomes [38–40].

Arthroscopy is performed under general anesthesia with an interscalene block of the brachial plexus. Examination under anesthesia shows a positive posterior drawer sign that confirms the diagnosis of posterior instability (Fig. 21.5a, b). The patient lies in lateral decubitus position with the shoulder in approximately 30° of abduction and 15° of forward flexion and a traction of 5 kg applied to the arm. After establishing a posterior portal about 2 cm inferior to the posterior acromial angle [41], the anterior-superior portal is created by the inside-out technique using a Wissinger rod [42]; finally, an accessory superolateral portal is created with the in-out technique [38]. The diagnosis of posterior instability is confirmed when a reverse Bankart lesion [39] is detected from the anterior portal (Fig. 21.6). The posterior-inferior capsular redundancy is evaluated first with the aforementioned intraoperative drawer sign, to determine the posterior subluxation of the humeral head, and next with a probe to test the elasticity of the posterior capsular tissue. One or two absorbable suture anchors are placed on the posterior glenoid to repair the reverse Bankart lesion (Fig. 21.7a, b). One or two posterior capsular plications are generally required to tighten the capsule; the anterior capsule may also be plicated if redundant. The capsule is shifted superiorly using curved suture hooks (Linvatec, Largo, FL, USA) and sutured to the posterior labrum with sliding knots. Our group and other colleagues [36] consider large, engaging reverse Hill-Sachs lesion, large reverse bony Bankart lesion, and reverse HAGHL as contraindications for arthroscopic treatment of posterior shoulder instability. In patients with previous failed surgery, we prefer arthroscopy-assisted posterior shoulder stabilization using an iliac bone graft [43].