17

Posterior Interosseous Syndrome

William B. Geissler

History and Clinical Presentation

A 52-year-old right hand dominant carpenter and avid golfer presented with complaints of pain well localized to the right extensor muscle mass just distal to the elbow joint that had persisted for 6 months. He describes the pain as aching in character with burning that radiates along the anatomic course of the forearm extensor muscles. He has noticed a slowly enlarging mass over the dorsal proximal forearm and complains of weakness in grip strength and diminished endurance. He has no complaints of sensory loss to the hand or forearm. He denies any history of trauma.

Physical Examination

The right forearm measured 2 cm larger than the left in circumference and measured 5 cm distal to the lateral epicondyle. A palpable mass was noted over the dorsal proximal forearm, and the patient was tender to palpation over the radial nerve as it passed through the mobile muscle mass at and just distal to the radial head. Slight tenderness to palpation was noted over the same area to the left forearm but not as severe. Palpation directly over the lateral epicondyle caused mild discomfort, less severe than over the course of the nerve. Full passive flexion of the wrist and fingers with the elbow in extension reproduced the pain. Resisted supination with the extended arm similarly reproduced the pain symptoms. Radial deviation was observed with wrist extension. The patient was able to fully extend the interphalangeal joints, but he could not fully extend the metacarpophalangeal joints beyond 45 degrees.

PEARLS

- Brachioradialis splitting approach provides excellent easy exposure to the radial tunnel for decompression.

- Easier to identify nerve proximally and trace out distally

- Consider posterior approach for mass compressing distal aspect of radial tunnel.

PITFALLS

- Beware of cervical radiculopathy presenting as posterior interosseous syndrome. No sensory symptoms in posterior interosseous syndrome.

- Beware tendon rupture in rheumatoid patients presenting as posterior interosseous nerve syndrome. Treatment is entirely different.

- Revisions usually secondary to incomplete release of nerve through supinator. Compression of posterior interosseous nerve has been reported at distal edge of supinator.

Diagnostic Studies

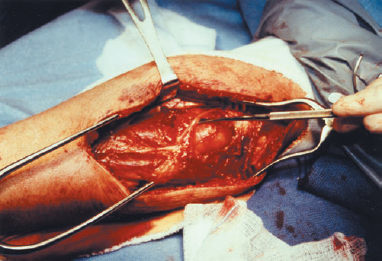

Anteroposterior, lateral, and oblique radiographs of the right elbow did not show any bony abnormalities. An abnormal soft tissue shadow was noted on the lateral radiograph dorsally. Magnetic resonance imaging of the proximal forearm revealed a mass consistent with a lipoma involving the supinator muscle (Fig. 17–1). Electromyographic and nerve conduction studies of the bilateral upper extremities demonstrated denervation of the extensor digitorum communis and extensor carpi ulnaris. The abductor pollicis longus and extensors pollicis longus and brevis were spared.

Figure 17–1. Magnetic resonance image demonstrating a large lipoma overlying the proximal radius. Note the distended supinator muscle.

Differential Diagnosis

Radial tunnel syndrome

Cervical radiculopathy

Lead poisoning

Systemic connective tissue disease

Hysterical wrist drop

Posterior interosseous syndrome

Diagnosis

Posterior Interosseous Syndrome

Radial tunnel syndrome involves compression of the posterior interosseous nerve branch of the radial nerve. Radial tunnel syndrome is defined when there is an absence of muscular involvement and the diagnosis of posterior interosseous syndrome is defined when there is muscular weakness and atrophy in the efferent distribution. The posterior interosseous nerve is not a purely motor nerve. It carries gamma-afferent fibers from the muscles it innervates. This can be demonstrated by the discomfort experienced by squeezing any muscle belly. The posterior interosseous nerve also supplies sensory afferent fibers to the radiocarpal, intercarpal, and carpometacarpal joints. Patients describe an aching, burning discomfort in the mobile extensor wad musculature, which may radiate distally down the forearm.

The radial nerve rises from the posterior cord of the brachial plexus. About 4 cm proximal or distal to the radiocapitellar joint, the radial nerve divides into two large terminal branches: the radial sensory and posterior interosseous nerves. Anatomic compressive factors in posterior interosseous syndrome include the fibrous bands from the anterior capsule, origin of the extensor carpi radialis brevis, radial recurrent leash of vessels, and the arcade of Frohse. These structures compress the nerve in elbow extension, passive forearm pronation with wrist flexion, and resisted supination. Active forearm supination has been reported to produce five times greater pressure than passive forearm pronation.

Unlike radial tunnel syndrome, many causes of posterior interosseous nerve syndrome other than purely anatomic have been described. Trauma primarily resulting in radial head fracture or dislocation may result in palsy of the posterior interosseous nerve. Any space-occupying lesions may compress or injure the nerve in the radial tunnel. Ganglions, lipomas, and fibromas have all been reported to compress the posterior interosseous nerve with resulting muscle weakness. Magnetic resonance imaging may be helpful if a mass is suspected. The posterior interosseous nerve may become compressed in patients with rheumatoid arthritis secondary to inflammation or subluxation of the radial head. This can be differentiated by the tenodesis effect by flexion and extension of the wrist.

Pain is frequently the primary initial complaint followed by muscle weakness or paralysis, which may develop over a period of several weeks. Occasionally, weakness may occur dramatically overnight following unaccustomed exercise. The sequence of muscular involvement follows no set pattern. Patients with motor involvement may notice weakness and radial deviation with wrist extension. This is because the radial nerve proximal to the radial tunnel innervates the extensor carpi radialis longus and brevis. Patients maintain the ability to extend the interphalangeal joints of the fingers, but may be unable to extend the metacarpophalangeal joints beyond 45 degrees. Partial paralysis may result in the loss of extension of the small and ring fingers alone, producing the false appearance of an ulnar claw hand. However, the metacarpophalangeal joints would not be hyperextended and the ulnar nerve intrinsic musculature would be intact. Thumb extension may or may not be involved. There is no sensory loss.

Differential Diagnosis

Other conditions that must be differentiated from posterior interosseous nerve syndrome include cervical radiculopathy, inflammatory arthritis, lead poisoning, and hysterical wrist drop. Radial tunnel syndrome is defined when there is lack of motor involvement.

Examination of the elbow should always include an evaluation of the cervical spine. A Spurling’s maneuver is helpful to evaluate for cervical radiculopathy along with a thorough neurologic examination. Cervical radiographs should be performed if there is any question of cervical involvement. Patients with cervical pathology also usually present with sensory symptoms.

Patients with rheumatoid arthritis may present with sudden loss of metacarpophalangeal extension secondary to acute extensor tendon rupture or posterior interosseous nerve palsy. Patients with posterior interosseous nerve palsy may be differentiated from ruptured extensor tendons by examining the tenodesis effect of wrist flexion-extension. The metacarpophalangeal joints extend with wrist flexion if the extensor tendons are intact, suggesting that the lack of extension is secondary to posterior interosseous nerve palsy. Electromyographic studies also are helpful in this situation.

Lead poisoning may produce a high radial nerve palsy without sensory loss. Patients would then present with involvement of the brachioradialis and radial wrist extensors. Lead poisoning is further confirmed by classical gingival discoloration and by blood and urine studies. Hysterical wrist drop presents with inability to extend both the interphalangeal and metacarpophalangeal joints (Table 17–1).

| Diagnosis | Differentiating Findings |

| Radial tunnel syndrome | No motor involvement |

| Cervical radiculopathy | Spurling’s maneuver |

| Distal sensory complaints | |

| Altered reflexes | |

| Abnormal cervical radiograph | |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | Positive rheumatoid factor |

| Wrist tenodesis effect | |

| Lead poisoning | High radial nerve palsy |

| Weak radial wrist extensors | |

| Positive blood/urine studies | |

| Hysterical wrist drop | Inability to extend interphalangeal joints with metacarpophalangeal joints in flexion |

Nonsurgical Management

Nonsurgical management of posterior interosseous syndrome includes rest, splinting, and activity modifications. Oral antiinflammatory agents may be helpful, primarily for pain relief. Corticosteroid injections generally have minimal benefit because the neuropathology is compression, not active synovitis.

Job or avocation changes may be of some benefit. Appropriate splintage should be provided if muscle paralysis is present. It is extremely important to emphasize full passive range-of-motion exercises to the involved joints in cases of muscle paralysis to prevent contracture. Patients with acute motor weakness without evidence of a mass may demonstrate spontaneous recovery.

Surgical Management

Indications for surgical management include clinical or electrophysiologic denervation without change or improvement over 60 to 90 days. Patients with a confirmed mass compressing the radial tunnel should be considered primarily for surgical management. A symptomatic radial tunnel that progresses to extensor motor paralysis is an indication for operative decompression.

The radial tunnel may be decompressed through one of three approaches—brachioradialis-splitting, anterior, and dorsal—which have all been described to release the radial tunnel. The brachioradialis-splitting approach provides excellent exposure to the entire radial tunnel and is easy to perform. The dorsal approach may be utilized particularly when a mass is present involving primarily the supinator muscle.

Brachioradialis-Splitting Approach

A 6-cm curved or straight incision is made over the mobile wad starting at the level of the cubital fossa and extending distally. Dissection is bluntly taken down to the fascia to protect the cutaneous nerves. The brachioradialis is then bluntly split, aiming toward the radial head. Blunt dissection and retraction with a blunt retractor reveal the radial nerve within a fibrofatty layer. Dissection proximally demonstrates the radial nerve as it divides into the posterior interosseous and the sensory nerve branches. The fibrous bands are released over the radial nerve. Bipolar electrocautery is necessary to release the leash of recurrent radial vessels. The posterior interosseous nerve is then traced as it passes under the proximal edge of the extensor carpi radialis brevis. Occasionally, the nerve gives off motor branches to the muscle at this location, and these need to be protected. The proximal edge of the supinator (Arcade of Frohse) is then identified. Care must be taken to identify the proximal edge of both the extensor carpi radialis brevis and the supinator. It is easy to release only the extensor carpi radialis brevis, thinking this was the supinator. The supinator should be released throughout its entire length in posterior interosseous syndrome. Meticulous hemostasis is mandatory before closure.

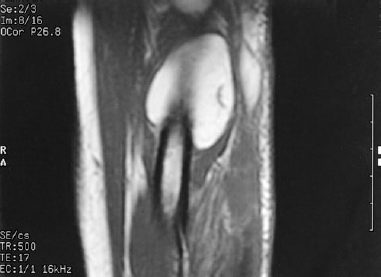

Posterior Approach

The posterior approach is useful when a mass is present in the supinator causing muscle paralysis, as more distal decompression of the nerve is easier from this approach. A 6-cm incision is made over the dorsal proximal forearm parallel with an imaginary line extending from the lateral epicondyle to Lister’s tubercle. The interval between the extensor carpi radialis brevis and extensor digitorum communis is developed. This interval is easier to develop distally than proximally. The posterior interosseous nerve is identified as it exits distally through the supinator and is traced proximally (Figs. 17–2 and 17–3).