19

Posterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction with Achilles’ Tendon Allograft

Over the past several years, basic science information regarding the anatomy and biomechanics of the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) has grown, providing the clinician with an increased understanding of the treatment of these injuries. The most common mechanisms of injury are a posterior load on a flexed knee, hyperflexion, and hyperextension injury. The PCL is the primary restraint to posterior translation of the tibia on the femur and a secondary restraint to external rotation of the tibia.1–3 Knowledge of the function of the ligament is the key to making the diagnoses on the injured knee. The cornerstone of diagnosis is the posterior drawer test, which is performed by placing a posterior stress on the tibia at 90 degrees of flexion. Isolated PCL injuries can be classified as partial or complete, which can usually be determined by physical examination. Partial injuries are most often the result of a hyperflexion mechanism wherein the anterolateral bundle is ruptured but the posteromedial bundle remains intact. Clinically, a partial PCL tear is distinguished by a posterior drawer of 1 + to 2 +. In general, partial isolated PCL injuries have a good prognosis and are amenable to nonoperative management.4, 5 Grade I injuries have a palpable anterior stepoff of the tibia, but less than normal (0 to 5 mm). Grade II injuries have lost the anterior stepoff and the tibia starts flush with the femur, but the tibia cannot be pushed posterior to the femur (>6 to 10 mm). Grade III injuries have an obvious posterior sag, and the tibia can be pushed posterior to the femoral condyle (>10 mm).

Complete tears of the PCL must be distinguished from combined ligament injuries because the prognosis is different for these injuries. Combined ligament injuries need to be diagnosed in a timely fashion and neurovascular injury ruled out, with operative ligament repair undertaken in less than 3 weeks. This chapter addresses the indications and technique of reconstruction of the anterolateral bundle of the PCL with Achilles’ tendon allograft. Because of its biomechanical and anatomic superiority, we reconstruct the anterolateral bundle when only one bundle of the PCL is reconstructed. The Achilles’ tendon allograft is an excellent graft for this reconstruction because of its ease of passage, lack of donor-site morbidity, and length.6

Surgical Indications and Other Treatment Options

In general, isolated grade I and II PCL injuries do well with nonoperative management. Our indications for single-bundle PCL reconstruction have narrowed over the past several years with the development of double-bundle techniques. Currently, single-bundle reconstruction of the anterolateral bundle with Achilles’ tendon allograft is performed only in the acute setting (<3 weeks) for combined PCL injuries or isolated grade III injuries in athletes. In the setting of a chronic PCL tear, there tends to be increased laxity in the primary and secondary restraints. Thus, chronic grade III isolated injuries associated with instability and chronic combined injuries are reconstructed with a double-bundle technique, which has been shown in a laboratory setting to provide greater restraint to posterior translation.7 Chronic grade II PCL tears and grade III injuries with pain are treated with a biplanar high tibial osteotomy to correct varus alignment and increase posterior slope.

Surgical Techniques

Patient Positioning

The patient is positioned supine on a regular operating room table with a sandbag taped to the table at the foot of the bed to hold the leg at 90 degrees of knee flexion. A standard side post is used at the level of the midthigh to provide a fulcrum for valgus stress and to provide lateral support with the knee at 90 degrees of flexion. A tourniquet is applied to the upper thigh but is inflated only if needed, which is rare. The extremity is prepped from the tourniquet distally with alcohol and Betadine and draped with an impervious stockinette, an extremity drape, and a half sheet to cover the post. A bolster is placed between the lateral thigh and the post.

The operating room should be organized to provide a controlled environment where operating staff traffic and the potential for contamination are kept to a minimum. It is necessary to have a separate table for graft preparation that has an oscillating saw, drill, and soft tissue instruments.

Operative Technique

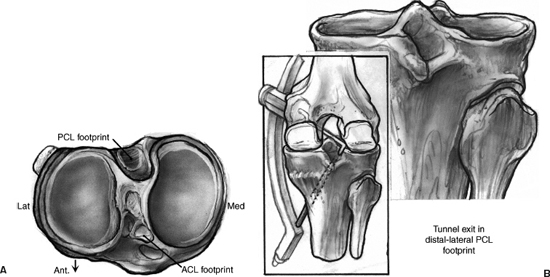

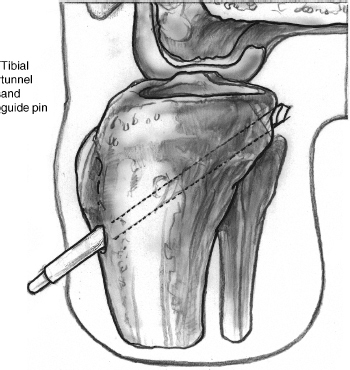

It is necessary to perform a thorough examination under anesthesia prior to the start of the operative procedure to assess the exact pathology that needs to be addressed. All incision sites and the joint are marked prior to prepping and draping, prepped out with a Betadine stick, and injected with 1% lidocaine with epinephrine. We utilize arthroscopic techniques as much as possible to avoid extensive soft tissue dissection. In the setting of an acute, combined injury gravity inflow is used to limit the possibility of extravasation of fluid into the soft tissues and risk a compartment syndrome. A standard arthroscopy is performed, utilizing an anterolateral viewing portal and an anteromedial working portal. The PCL tear is confirmed, and the remnants are debrided using a combination of shavers and curettes through the anterior portals and a posteromedial portal. Extreme care is taken during exposure of the tibial insertion as the neurovascular structures are closely situated. The posteromedial portal is used to view the tibial insertion site with both 70- and 30-degree arthroscopes and to assist in debridement with a shaver. Using a commercially available PCL tibial aiming guide through the medial portal, a 3/32-inch Kirschner wire (K-wire) is then passed from the anteromedial tibia to the distal and lateral aspect of the insertion of the PCL (Fig. 19-1), which is approximately 1 cm below the articular surface in the tibial sulcus. The tunnel is angled so that it parallels the proximal tibiofibular joint. Care is taken to leave at least 2 cm between the PCL and anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tunnels if they are being reconstructed together. Tibial tunnel placement is confirmed with an intraoperative lateral radiograph. The guide pin is protected during drilling from migration and possible neurovascular injury using a PCL curette through the medial portal while viewing through the posteromedial portal (Fig. 19-2). A 10 to 11 mm tunnel is drilled on both the tibial and femoral sides.

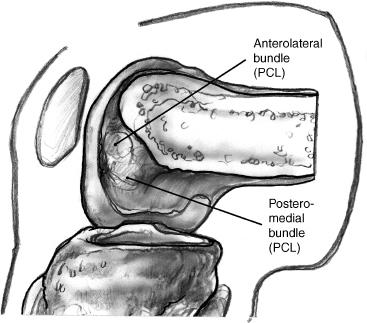

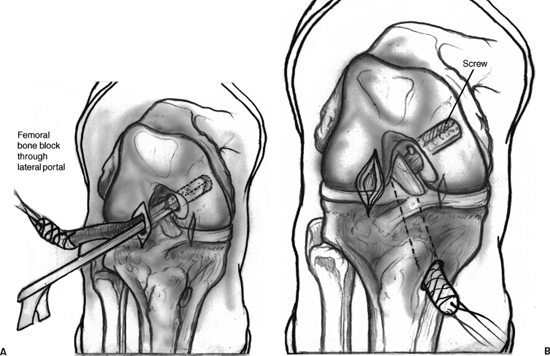

The femoral tunnel is created either with an outside-in, open technique or using an arthroscopic technique through the lateral portal. We prefer to create the tunnel and pass the graft arthroscopically when possible. A 3/32-inch K-wire is passed from the anterolateral portal to the center of the anterolateral bundle origin (Fig. 19-3), and a 10 to 11 mm tunnel is drilled to a depth of 25 mm. The anterior edge of the tunnel should abut the articular surface. Graft preparation is performed using a No. 5 braided, nonabsorbable suture in a whipstitch fashion at the soft tissue end, and the bone plug is prepared to correspond to the size of the femoral tunnel (Fig. 19-4). The bone block is passed first through the enlarged anterolateral portal and into the femoral tunnel. The graft is situated so the tendinous portion is placed anterior. Through the lateral portal an interference screw is placed on the posterior side of the tunnel adjacent to the cancellous portion of the bone block. A bent 18-gauge wire loop is pulled through the tibial tunnel and out the lateral portal for use as a graft passer. The tendinous portion of the graft is then passed through the lateral portal and tibial tunnel (Fig. 19-5). A 4.5 mm screw and soft tissue washer are used to fix the Achilles’ tendon to the anteromedial tibia. The graft is fixed at 90 degrees of flexion with an anterior drawer to re-create the normal 1 cm anterior tibial stepoff.

Figure 19-1 (A) Footprint of the native posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) insertion. (B) The tunnel should exit in the distal and lateral aspect of the tibial PCL footprint. (From Miller MD, Harner CD, Kashiwaguchi S. Acute posterior cruciate ligament injuries. In: Fu FH, Harner CD, Vince KG, eds. Knee Surgery. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1994:749–768.)

Figure 19-2 The tibial tunnel is drilled while the guide pin is viewed at all times through the posteromedial portal. A curette is used to prevent migration of the Kirschner wire (K-wire). (From Miller MD, Harner CD, Kashiwaguchi S. Acute posterior cruciate ligament injuries. In: Fu FH, Harner CD, Vince KG, eds. Knee Surgery. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1994:749–768.)

Figure 19-3 Femoral location of the anterolateral bundle of the PCL. The anterior edge of the tunnel should be adjacent to the articular surface. (From Miller MD, Harner CD, Kashiwaguchi S. Acute posterior cruciate ligament injuries. In: Fu FH, Harner CD, Vince KG, eds. Knee Surgery. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1994:749–768.)

Figure 19-4 Prepared Achilles’ tendon allograft with a No. 5 whipstitch on the tendon end.

The open technique involves a 3 cm incision 1 cm medial to the medial border of the patella. An ACL guide is used to pass a K-wire from the flare of the medial cortex of the medial femoral condyle through to the intercondylar notch in the footprint of the anterolateral bundle. The tunnel is drilled, and the tendinous end of the graft is passed antegrade through the femoral and then tibial tunnels. It is fixed in the same manner as described above.

Postoperative rehabilitation involves immobilization of the knee in full extension for 2 to 4 weeks, during which the patient performs isometric quadriceps rehabilitation. The patient is allowed partial weight bearing with crutches. Immobilization in full extension is preferred because it gives the graft a chance to heal while minimizing the posterior forces that occur with gravity and hamstring contraction.6, 8, 9 Loss of flexion rarely occurs with isolated PCL reconstructions, but an occasional manipulation under anesthesia at 6 to 8 weeks is required. At 4 weeks passive motion is begun, with the physical therapist applying an anterior drawer to the tibia. Active flexion is not allowed for 8 weeks because of the tendency of the hamstrings to sublux the tibia posteriorly.

Tips and Tricks

- We have found the posteromedial portal to be invaluable in localizing and creating the tibial insertion during PCL reconstructions. In heavy patients a small (2 cm) posteromedial incision is sometimes necessary to dissect down to the capsule. Through the posteromedial portal a 30- or 70-degree arthroscope can be placed as well as a shaver to assist with the debridement of the tibial stump.

Figure 19-5 Graft passing sequence. (A) The femoral bone block is passed through the lateral portal, into the femoral tunnel, and secured with an interference screw. (B) The tendon end of the graft is passed through the lateral portal and through the tibial tunnel to exit the anteromedial tibia.

- We have found that a looped, slightly bent 18-gauge wire is the best means to retrieve the sutures to pass the graft. The wire is passed retrograde through the tibial tunnel, retrieved with an arthroscopic grasper, and pulled out the medial portal, where it is clamped until the femoral side is passed and fixed. It is then passed to the lateral portal to pass the graft suture.

- The arthroscopic passage and fixation of the femoral bone block can be difficult. The lateral portal needs to be enlarged to about 2 cm to accommodate both the graft and the arthroscope. The bone block sutures are passed via a Beath pin through the lateral portal and out the anteromedial thigh. The bone block is then pulled into place in the tunnel. Because the tendinous portion of the bone plug is anterior, it is difficult to view the posterior edge of the bone to insert the flexible wire for the interference screw. An enlarged portal allows the arthroscope to be placed alongside the graft to view the posterior insertion site for the interference screw.

- Care should be taken to plan incisions in the knee with multiple ligament injuries, leaving at least a 7 cm skin bridge between incisions. Healing of incisions can be problematic in the traumatized knee, and excess retraction must not be placed on the skin during the surgery. Incisions should be lengthened if there is excess tension.

- We have found that a looped, slightly bent 18-gauge wire is the best means to retrieve the sutures to pass the graft. The wire is passed retrograde through the tibial tunnel, retrieved with an arthroscopic grasper, and pulled out the medial portal, where it is clamped until the femoral side is passed and fixed. It is then passed to the lateral portal to pass the graft suture.

Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

- Neurovascular injury is a dreaded complication of any surgery but is higher in PCL reconstruction because of the proximity of the structures to the tibial attachment site. The popliteal artery, vein, and tibial nerve run directly posterior to the tibial insertion of the PCL. Extreme care must be taken during debridement of the stump. Elevating a small portion of the posterior capsule off the tibia with a PCL curette helps to improve exposure. The K-wire must be visualized at all times and protected from migrating during the drilling of the tibial tunnel with a curette. We begin to drill the tunnel with power but finish the last several centimeters by hand.

- The graft needs to be prepared so there is no excess soft tissue on the tendinous end that causes it to get caught in the tibial tunnel during passage. Extra soft tissue is excised, and a tight whipstitch is used to tubulerize the end of the graft.

- When performing a concomitant medial or lateral side reconstruction, the PCL graft is passed and fixed on the femoral side, but the tibial side is not fixed until the other ligaments are exposed and ready to be fixed. This is because the medial and lateral repairs can sometimes be lengthy and can place unnecessary tension on a fixed PCL graft. Care must be taken during movement of the knee after fixation to always provide an anterior drawer to the tibia.

Conclusion

Distinguishing between an isolated and a combined PCL injury is critical to providing the correct treatment and allowing for the best outcome. PCL reconstruction with Achilles’ tendon allograft is a useful technique in the acute setting for reconstruction of isolated grade III injuries and combined ligament injuries. We choose to reconstruct the anterolateral bundle of the ligament because of its superior biomechanical and anatomic characteristics, and this needs to be performed with a graft of sufficient size and strength, such as the Achilles’ tendon. Reconstruction of the PCL and associated injuries is a complex undertaking, and the surgeon needs to be familiar with multiple graft options and fixation techniques.

References

1 Gollehon DL, Torzilli PA, Warren RF. The role of the posterolateral and cruciate ligaments in the stability of the human knee. A biomechanical study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1987;69:233–242

2 Grood ES, Stowers SF, Noyes FR. Limits of movement in the human knee. Effect of sectioning the posterior cruciate ligament and posterolateral structures. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1988;70:88–97

3 Veltri DM, Deng X-H, Torzilli PA, et al. The role of the cruciate and posterolateral ligaments in stability of the knee. A biomechanical study. Am J Sports Med 1995;23:436–443

4 Fowler PJ, Messieh SS. Isolated posterior cruciate ligament injuries in athletes. Am J Sports Med 1987;15:553–557

5 Parolie JM, Bergfeld JA. Long term results of nonoperative treatment of isolated posterior cruciate ligament injuries in the athlete. Am J Sports Med 1986;14:35–38

6 Harner CD, Jurgen H. Evaluation and treatment of posterior cruciate ligament injuries. Am J Sports Med 1998;26:471–482

7 Harner CD, Janaushek MA, Kanamori A, et al. Biomechanical analysis of a double-bundle posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med 2000;28:144–151

8 Ogata K, McCarthy JA. Measurements of length and tension patterns during reconstruction of the posterior cruciate ligament. Am J Sports Med 1992;20:351–355

9 Renstrom P, Arms SW, Stanwyck TS. Strain within the anterior cruciate ligament during hamstring and quadriceps activity. Am J Sports Med 1986;14:83–87

< div class='tao-gold-member'>