Introduction

The shoulder forms a foundation from which the whole of the upper limb can move. Acting like the cab of a crane, the shoulder allows the hand to be placed in all directions around the body, in the same way as the jib of a crane places its load. In upper limb function, the hand can be held high above the head, in front, behind, to the side and across the body, and touching the body. The role of the shoulder is to position the hand over this wide area.

The shoulder not only performs a wide range of movement but also anchors the arm to the trunk, supporting the weight of the upper limb as it moves. The main strut for this purpose is the clavicle, part of the shoulder (pectoral) girdle formed by the clavicle and scapula. When the hand performs precision movements, stability is provided by the joints of the girdle and all the muscles surrounding the shoulder. The shoulder joint is not part of the pectoral girdle but they are mutually dependent in all the movements of the upper limb. Figure 5.1 shows how both the humerus and the scapula both move when the arm is moved towards the vertical.

Movements at the elbow change the functional length of the upper limb, adjusting the distance of the hand from the body. Elbow flexion brings the hand towards the head and body for activities, such as washing, dressing, eating and drinking. Try splinting the elbow in extension to find out how much we depend on elbow flexion for daily activities. The opposite action of elbow extension takes the hand away from the body in reaching and grasping, and also enables the hand to push against resistance, for example sawing wood or pushing a swing door. A person with reduced lower limb function relies on the elbow extensors, together with shoulder muscles, to lift the body weight on the hands to rise from a chair.

Figure 5.1 Posterior view of the scapula and humerus: (a) anatomical position; (b) arm vertical.

Movements of the shoulder, which involve the shoulder girdle and the shoulder joint, will be considered first, followed by the elbow. Upper limb movements depend on the co-operation of the shoulder and the elbow in positioning the hand.

PART I: THE SHOULDER

The shoulder (pectoral) girdle

Position and function

The bones of the shoulder girdle are the clavicle and the scapula. The clavicle articulates at its medial end with the sternum of the thorax. The scapula is a large, flat triangular bone lying on the ribs, separated by a layer of muscle, in the posterior aspect of the thorax. The scapula is suspended by the muscles attached to its borders and surfaces so that it moves freely on the chest wall. The posterior surface of the scapula has a projecting spine which ends at the acromion process. The lateral end of the clavicle articulates with the acromion process. The head of the scapula lies laterally and has the glenoid fossa, a shallow concavity, for the articulation with the head of the humerus. From the upper part of the head, the coracoid process projects upwards and forwards to lie below the clavicle. The coracoid process provides a base for one of the proximal tendons of the biceps muscle lying on the anterior aspect of the arm.

All movements of the pectoral girdle involve both the clavicle and the scapula together. The movements of the scapula follow the shape of the ribs. The scapula is able to move freely on the thorax, because the muscles between the ribs and the scapula are covered by fascia which allows gliding movements. When the scapula moves on the chest wall, the glenoid fossa is turned to face in different directions, i.e. more directly forwards, backwards, upwards or downwards. This allows the humerus to move further in that particular direction and therefore increases the range of movement at the shoulder joint. If the shoulder girdle becomes fixed, all upper limb activites are restricted and compensation for the reduced range of movement can only be achieved by a shift of the whole body.

In summary, the functions of the shoulder girdle are:

- to anchor the upper limb to the trunk by means of the strut-like clavicle;

- to define the position of the shoulder joint and consequently the direction of the movements of the arm on the trunk;

- to increase the range of movement at the shoulder joint by changes in the angulation of the clavicle and in the position of the scapula on the chest wall.

Joints of the shoulder (pectoral) girdle

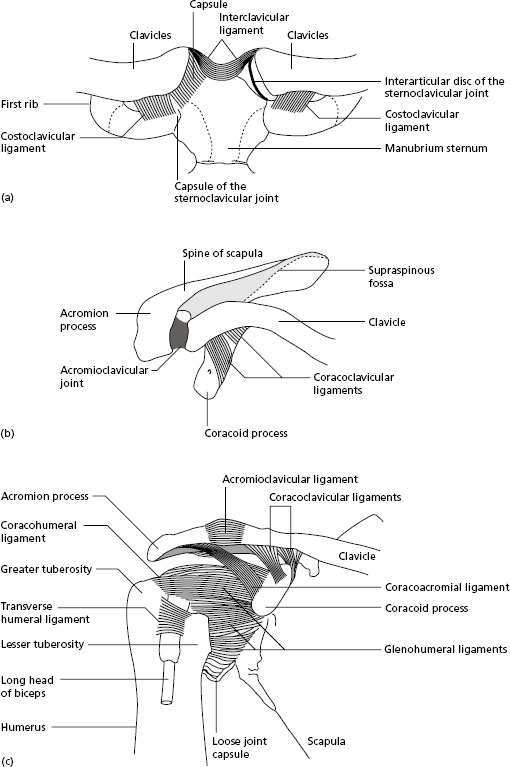

Two articulations are involved in the shoulder girdle. The sternoclavicular joint is a synovial joint between the medial end of the clavicle and the clavicular notch on the manubrium of the sternum. It is divided by an intra-articular disc of fibrocartilage joining the upper end of the clavicle to the first costal cartilge at its sternal end (Figure 5.2a). A strong costoclavicular ligament joins the medial end of the clavicle to the first rib, and the interclavicular ligament joins the medial ends of the right and left clavicles. The disc, together with the ligaments, prevents dislocation of the joint during falls on the outstretched arm or when a heavy load, for example a suitcase, is carried in the hand.

The acromioclavicular joint is a synovial joint that connects the lateral end of the clavicle with the acromion process of the scapula. The capsule is thickened by strong fibres both superiorly and inferiorly. The main factor stabilising the joint is the strong coracoclavicular ligament joining the lateral end of the clavicle to the coracoid process of the scapula (Figure 5.2b).

Summary of the movements of the shoulder girdle

For the purpose of description, the movements of the shoulder girdle are divided as follows:

- elevation: the scapula moves upwards together with the lateral end of the clavicle. This movement is commonly described as ‘shrugging the shoulders’;

- depression: the scapula and lateral end of the clavicle move down to the resting position;

- protraction: the scapula moves laterally around the chest wall bringing the glenoid fossa to face more directly forwards. The vertebral border of each scapula (see Appendix I ) moves further away from the spine;

- retraction: the scapula moves medially around the chest wall bringing the glenoid fossa to face more directly towards the side. The vertebral border on each scapula moves nearer to the spine;

- lateral rotation: the inferior angle of the scapula moves laterally and the glenoid fossa points upwards;

- medial rotation: the inferior angle of the scapula moves medially and the glenoid fossa returns to the resting position.

These movements of the shoulder girdle increase the range of movement at the shoulder joint. Elevation increases reaching upwards, while depression increases pointing downwards. Protraction takes the hand farther across the body to reach to the opposite side, and retraction takes the hand farther behind the body. Abduction or flexion of the arm, which takes the hand above the head, is increased in range by lateral rotation of the scapula.

Figure 5.2 (a) Sternoclavicular joints, anterior view (left joint with capsule removed); (b) right acromioclavicular joint, superior view; (c) right glenohumeral joint, anterior view.

- Palpate the scapula on a partner whose horizontal arm swings round a wide circle forwards and backwards. Feel the movement of protraction as the arm swings across the front of the body, and retraction as it swings behind the body.

- Lift the arm of a partner through the full range of abduction to reach above the head, then full adduction back to the side. Palpate the scapula during this action. Lateral rotation can be felt as the arm is raised, then medial rotation as the arm is lowered.

The shoulder (glenohumeral) joint

The bony articulation of the shoulder joint occurs between the head of the humerus and the shallow glenoid fossa on the lateral aspect of the scapula (Figure 5.2c). The glenoid fossa is deepened by a rim of fibrocartilage, the glenoid labrum. The head of the humerus is approximately one-third of a sphere, but only one-third of its surface area is in contact with the glenoid fossa during movement. The fibrous joint capsule is both thin and loose. The shape of the bony surfaces and the loose capsule both provide for a wide range of movement at the joint, but they present a poor prospect for stability.

Some support is given by two ligaments. The coracohumeral ligament extends from the coracoid process to the upper aspect of the greater tuberosity of the humerus. This ligament assists in holding the head of the humerus up to the glenoid fossa, but it is not entirely successful in this. An accessory ligament joins the coracoid and acromion processes to form an arch over the head of the humerus. This coracoacromial ligament prevents upward dislocation of the head of the humerus, for example in a fall on to the abducted arm.

Muscles join the humerus to the pectoral girdle around the anterior, posterior and superior aspects of the shoulder joint. These muscles suspend the upper limb from the pectoral girdle and also stabilise the shoulder joint. The tendon of the long head of the biceps muscle lies inside the shoulder joint from its origin on the superior part of the glenoid fossa. Lying in the groove formed between the greater and lesser tuberosities of the humerus, the tendon is surrounded by a synovial sheath, and emerges from the lower margin of the capsule to become the prominent anterior muscle of the arm.

Movements of the shoulder joint

The glenohumeral articulation is a synovial joint of the ball and socket type which has the greatest range of movement of all the joints of the body, together with a poor prospect for stability.

- Flexion movement carries the arm forwards and at an angle of 45 degrees to the sagittal plane.

- Extension is the return movement from flexion and continues to take the arm beyond the anatomical position.

- Abduction carries the arm sideways and upwards in the frontal plane. It depends on lateral rotation of the scapula beyond 30 degrees.

- Adduction returns the arm to the side.

- Medial rotation occurs about the long axis of the humerus, turning the anterior surface of the humerus medially. When the elbow is flexed, medial rotation at the shoulder takes the hand across the body as in folding the arms.

- Lateral rotation occurs about the long axis of the humerus, turning the anterior surface of the humerus laterally.

The movements of the shoulder joint, together with the pectoral girdle, are essential for the performance of all personal care and dressing activities.

Muscles of the shoulder region

The shoulder region has a large number of muscles which combine in various ways, grouping and regrouping in the performance of the movements of the upper limb. The muscles attached to the pectoral girdle anchor the scapula to the trunk, control the orientation of the glenoid fossa for movements at the shoulder joint, and stabilise the shoulder joint. Muscles with the latter function are known as the ‘rotator cuff’ muscles. Large triangular muscles, originating on the bones of the trunk and inserted into the humerus, act on the shoulder joint in its wide range of movement.

Muscles stabilising and moving the shoulder girdle

Muscles cross the anterior and posterior surfaces of the scapula, and are attached to its borders and processes. The muscles covering the anterior surface are sandwiched between the scapula and the ribs, and are loosely separated by connective tissue and fat, which allows the scapula to move freely on the chest wall. Four of the muscles moving the scapula originate from the vertebral column. It is important to understand clearly the position of the scapula in relation to the vertebral column, ribs and walls of the axilla, in order to appreciate the direction of pull of the muscles which turn the scapula in various directions.

There are six muscles attached to the triangular scapula that combine to produce these movements. The muscles are the trapezius, levator scapulae, rhomboid major and minor, serratus anterior and pectoralis minor. By pulling together in different combinations, these muscles can elevate, depress, protract, retract and rotate the scapula on the chest wall.

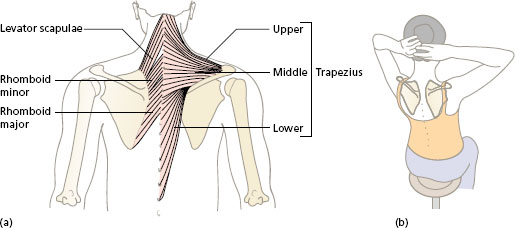

Figure 5.3 Trapezius, levator scapulae, rhomboid major and minor: (a) position; (b) reaching behind the head.

Trapezius

The two sides of the trapezius form a kite-shaped area of muscle, the most superficial muscle of the back. Each muscle is a triangle, with its base in the midline from the base of the skull down to the 12th thoracic spine (Figure 5.3a).

The upper fibres originate from the occipital bone of the skull and the ligamentum nuchae, which covers the cervical spines in the neck. The fibres pass downwards and forwards across the neck to the lateral end of the clavicle and continue on to the acromion of the scapula. Acting as a suspension for the pectoral girdle from the skull and neck vertebrae, contraction of these upper fibres lifts the shoulders in elevation. In addition, they give support to the shoulders when carrying heavy loads. The static work of the trapezius is felt when carrying heavy luggage or shopping.

The middle fibres pass horizontally from the upper thoracic spines to the length of the spine of the scapula. Contraction of these fibres pulls the scapula towards the spine and the scapula retracts. Activities involving this movement include reaching behind the head to comb the hair (Figure 5.3b) and to grasp a car seat-belt.

The lower fibres pass upwards from the lower thoracic vertebrae into a tendon that inserts into the base (medial end) of the spine of the scapula. Acting alone, these fibres will depress the shoulder when it has been raised. More important is the action of the lower fibres with the upper fibres to rotate the scapula, turning the glenoid fossa upwards during abduction of the arm.

Levator scapulae

The transverse processes of the first four cervical vertebrae provide the attachments for the levator scapulae, and the fibres descend to the vertebral border of the scapula above the spine (Figure 5.3a). The levator scapulae lies deep to the upper fibres of the trapezius and works with them to elevate the scapula.

Rhomboid major and minor

These two muscles form a continuous layer deep to the middle fibres of the trapezius, originating on the spines of the upper thoracic vertebrae, and insert into the medial border of the scapula (Figure 5.3a). The rhomboids can be considered as one muscle which pulls the scapula backwards in retraction.

Serratus a nterior

This has a saw-toothed origin from the upper eight or nine ribs, clearly seen in male swimmers and boxers with powerful shoulder muscles. From this wide origin, the fibres wrap round the thorax and underneath the scapula to be inserted into the vertebral border of the scapula (Figure 5.4a).

The action of the whole muscle pulls the scapula forwards around the chest in protraction. This movement increases the forward reach of the upper limb and adds to the force of an action pushing forwards against resistance, such as a door (Figure 5.4b).

The lower fibres of the serratus anterior converge on the inferior angle of the scapula, and their action will rotate the scapula laterally to turn the glenoid fossa upwards to allow full abduction of the humerus. In lateral rotation, the serratus anterior works with the upper and lower fibres of the trapezius.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree