Plantar Plate Repair of the Second Metatarsophalangeal Joint

Craig A. Camasta

Deformities of the second toe have challenged surgeons of all disciplines for nearly a century. Hammertoe, crossover toe, metatarsalgia, predislocation syndrome, and dislocated toe have all been used to describe a disorder of pain, inflammation, and subsequent instability around the second toe and metatarsophalangeal joint (MTPJ) (1,2 and 3). A variety of surgical procedures have been proposed to straighten the toe and reduce plantar pressure and pain. The most widely used procedures employ straightening of the digit via arthroplasty or arthrodesis, soft tissue rebalance around the MTPJ, flexor tendon transfer, metatarsal head resection with or without implant arthroplasty, or metatarsal osteotomy (1,4,5). However, none of these surgical procedures can consistently provide patients with a pain-free rectus toe that purchases the ground: metatarsal osteotomies intending to shorten or elevate the metatarsal head can leave the toe floating off the ground (surgically induced brachymetatarsalgia) (6,7,8 and 9), flexor tendon transfers can leave the patient with a painful stiff toe (10,11) with persistent plantar pain (12,13), and metatarsal head resection with/without implant arthroplasty is a joint destructive procedure that can alter normal joint function and lead to progressive arthritis and pain. Arthrodesis of the second MTPJ has been shown to effectively stabilize the crossover toe (14); however, too few studies have been done to support its widespread use. While sound in their approach, none of these procedures address the primary source of pain and instability around the second toe, which is inflammation, attenuation, or frank rupture of the plantar plate (15). Many studies have demonstrated the correlation of plantar plate pathology (rupture or attenuation) with second MTPJ metatarsalgia, synovitis, hammertoe, crossover toe, and second MTPJ contracture, subluxation, or dislocation (16,17). However, few studies have looked at primary repair of the plantar plate as a viable surgical option for addressing the pathology at the source (14,15,18,19,20,21,22 and 23), primarily due to reluctance to operate on the plantar surface of the foot (24). In this chapter, the author presents a comprehensive stepwise approach to diagnosing and treating plantar plate injuries and the various adjunctive procedures necessary to address the crossover second toe.

PATHOGENESIS OF PLANTAR PLATE DYSFUNCTION

Most patients with an unstable or painful second toe also have first ray insufficiency secondary to a hallux valgus deformity, which results in lateral weight transfer to the second MTPJ (13,23,25). Since the second metatarsal is locked in the mortise of the Lisfranc joint, it becomes the pivot point for the forefoot during propulsion. Differential weight transfer to the second MTPJ in patients with hallux valgus typically leads to one of two scenarios: proximal force transfer to the second metatarsal-cuneiform joint and degenerative arthritis at this level or a progressive second hammertoe deformity that parallels the degree of hallux valgus deformity, beginning with a sagittal contracture at the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) and MTPJ level, then medial and varus drift and subluxation of the MTPJ, and finally dorsal dislocation of the MTPJ (Fig. 19.1). Not every patient will progress to the next stage; however, nearly every patient experiences a period of significant pain and inflammation around the MTPJ that leads up to rupture of the plantar plate. Depending on the stage and duration of deformity, patients will present with different complaints. At the late stage, there may be no pain beneath the second toe as the disease process has run its course. The patient is left with a severe bunion and dislocated second toe whose primary symptoms are related to shoe irritation of the bunion and hammertoe (15). In other patients, the second MTPJ may remain subluxed long enough to cause dorsal erosion and degenerative arthritis of the MTPJ, and these joints may never progress on to dislocation.

DEMOGRAPHICS

Most patients with plantar plate insufficiency are female:male in a 10:1 ratio, and most patients are middle- to late middle-aged, ranging from late 20s in the athletic patients to mid 50s in the average patient. Some will present in their senior years having a long-standing untreated bunion and overlapping second toe that simply won’t fit into a shoe. Male and younger female patients tend to be athletic (runners, weight lifters, baseball catcher, etc.) or recall a traumatic event that precipitated their condition, such as running up a flight of stairs and stubbing the toe and feeling a sudden “pop” sensation beneath the toe (25). In female patients, plantar plate injuries tend to parallel the progression of a bunion deformity or occur more frequently with use of high-heel shoes (13,25).

Most interestingly, and without explanation, the author has observed that plantar plate insufficiency is a disease of Caucasians, having never encountered this condition otherwise, despite the fact that 45% of his patients are non-White (35% African American, 8% Hispanic, and 2% other).

DIAGNOSIS

Depending on the stage of deformity, signs and symptoms will vary at the initial time of presentation. Early-stage findings may be nothing more than plantar distal sulcus pain, with no/minimal digital deformity, first described by Yu as “predislocation syndrome” (2,3,10). Pain is typically not plantar to the metatarsal head where it is the most weight-bearing, but distal in the sulcus, which corresponds to where most ruptures occur. There is typically dorsal effusion around the second MTPJ and dorsal edema that occludes visualization of the extensor tendons, as compared with the contralateral limb (Fig. 19.2). The presence of dorsal effusion/edema around the MTPJs should give the clinician serious doubt to the diagnosis of a plantar neuroma, as a plantar neuroma would not likely create enough inflammation to extend to the dorsum of the foot.

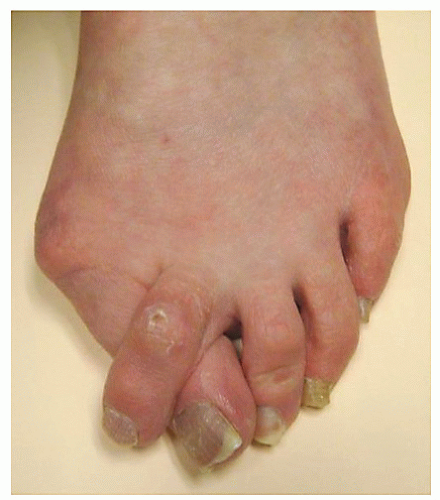

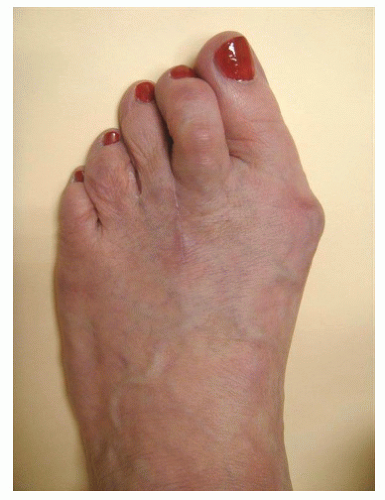

The most common sign of a ruptured plantar plate is the weight-bearing appearance of the second toe. If the toe is dorsally contracted at the MTPJ, with or without digital contracture, and the pulp of the toe is not able to purchase the ground, then one should suspect a ruptured or attenuated plantar plate (Fig. 19.3). A few exceptions to the correlation to a floating toe and plantar plate disruption include prior surgery with dorsal scar contracture or brachymetatarsia (possibly surgically induced by a shortening metatarsal osteotomy) (6). One may find it difficult to make this assessment if the second toe is overlapping the hallux, so the examination can be done nonweight-bearing by moving the hallux medially and performing a Kelikian push-up test. If the second toe does not reduce to the plane of the lesser toes, then one must suspect a plantar plate disruption.

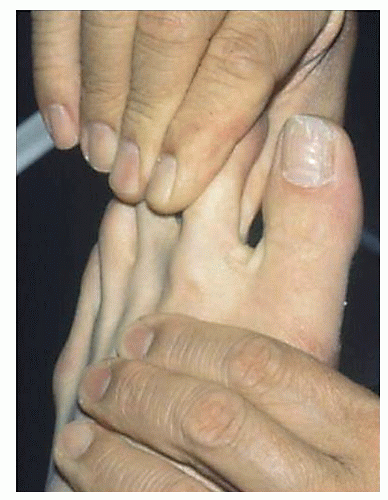

Range of motion of the MTPJ will vary from patient to patient, depending on the stage of the disease process. It may be from normal motion with no crepitation to rigidity of the toe and MTPJ. Dorsal excursion may elicit pain or guarding as one is performing a Lachman-drawer examination of the MTPJ (16). If the patient is acutely inflamed, one may wish to avoid attempting this test; however, if there is no significant pain or inflammation as in the late-stage condition, one may be able to freely sublux or dislocate the MTPJ (Fig. 19.4) (26,27).

A most helpful test to determine plantar plate insufficiency, even in patients with minimal digital contracture, is to perform

a plantar sling taping of the second toe (Fig. 19.5) (10). If the patient ambulates with significant reduction in pain following this maneuver, the suspicion of a plantar plate disruption or inflammation is reinforced. Additionally, the diagnosis of a plantar neuroma should be dissuaded. For many patients, this simple test confirms their diagnosis and can be employed as a conservative measure indefinitely. It is possible to arrest progression of this condition by sufficient off-weighting (avoidance of narrow or high-heeled shoes), activity modification (cross-training, avoidance of toe raise, or sprinting-type exercises), and tape strapping the toe plantarly for several months to allow for protected healing.

a plantar sling taping of the second toe (Fig. 19.5) (10). If the patient ambulates with significant reduction in pain following this maneuver, the suspicion of a plantar plate disruption or inflammation is reinforced. Additionally, the diagnosis of a plantar neuroma should be dissuaded. For many patients, this simple test confirms their diagnosis and can be employed as a conservative measure indefinitely. It is possible to arrest progression of this condition by sufficient off-weighting (avoidance of narrow or high-heeled shoes), activity modification (cross-training, avoidance of toe raise, or sprinting-type exercises), and tape strapping the toe plantarly for several months to allow for protected healing.

Figure 19.3 Typical appearance of a floating toe in a patient with a ruptured plantar plate (in the absence of scar tissue from prior surgery, or brachymetatarsia). |

Figure 19.4 Positive Lachman-Drawer test in a patient with a ruptured plantar plate, with the ability to dorsally dislocate the second MTPJ. |

MISDIAGNOSIS

Recognition and diagnosis of the inflamed or ruptured plantar plate has eluded physicians for many decades, as some of the presenting signs and symptoms can be misinterpreted as unrelated entities. Medial drift of the second toe with subsequent splaying of the second and third toes, coupled with pain at the distal sulcus of the second intermetatarsal space, has led many physicians to conclude that there is neuroma between the second and third metatarsal heads (26), often times large enough to cause splaying of the toes. In reality, medial drift of the toe is often a sign of plantar-lateral weakness or rupture of the plantar plate.

Treatment directed at an interdigital neuroma commonly includes injecting a corticosteroid preparation into the interspace or joint space, in an attempt to reduce inflammation and pain. However, this can further weaken an already inflamed plantar plate and cause it to rupture completely. Patients may recall a rapid progression of their deformity (dislocation) shortly following this type of injection therapy. In addition, many patients undergo attempted excision of a second interspace neuroma when the primary pathologic process is the inflamed or ruptured plantar plate.

Other conditions that should be considered, in descending order of frequency, include, but are not limited to, distal metatarsal stress fracture, Frieberg disease/osteonecrosis, systemic/autoimmune arthritis (rheumatoid, psoriatic, etc.), and gouty or infectious arthritis (26,27). Most other conditions can be ruled out by history and physical examination, basic radiologic testing, and serologic testing if indicated.

ANATOMY OF THE PLANTAR PLATE

The plantar plate is a fibrocartilagenous, cup-shaped, intraarticular plantar covering of the MTPJ whose superior surface is in direct contact with the metatarsal head. It is the distal-most and major insertion of the plantar fascia (28). The distal end of the plantar plate inserts into the base of the proximal phalanx, and medially and laterally it is continuous with the medial and lateral capsule of the MTPJ. There are no muscle/tendon insertions into the plantar plate; however, the inferior surface of the plantar plate houses the flexor tendons (longus and brevis) in a groove on the plantar-medial aspect of the metatarsal head. The deep fascia, including the deep transverse metatarsal ligament, contributes to the inferior/superficial surface of the flexor groove. The proximal extent of the plantar plate delineates the proximal recess of the plantar capsule of the MTPJ (Fig. 19.6). In patients with an inflamed or attenuated plantar plate, the thickness can be measured as great as 4 to 5 mm.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree