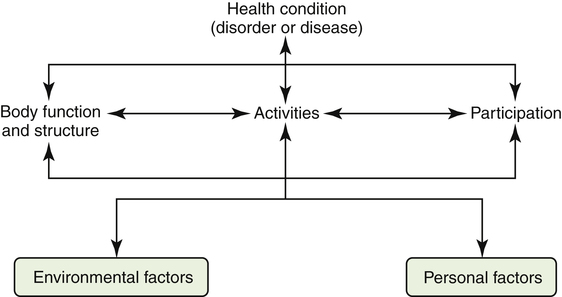

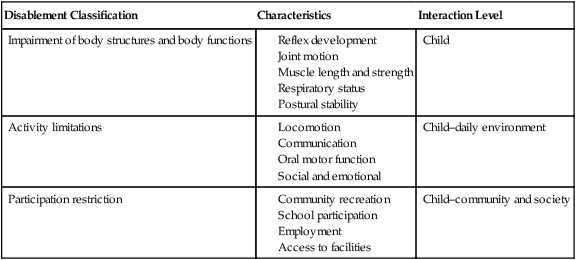

Karen W. Nolan and Angela Easley Rosenberg After reading this chapter, the reader will be able to: Congenital muscular torticollis (CMT) developmental coordination disorder (DCD) developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) goal-directed movement approach Individualized Education Plan (IEP) Individualized Family Service Plan (IFSP) juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA) neurodevelopmental treatment (NDT) pervasive developmental disorder (PDD) The priorities for pediatric therapists are to observe children as they portray their individual strengths and abilities and to promote a functional, optimal developmental process. By acquiring knowledge of normal development through observation of movement patterns and transitions, the therapist can more accurately detect abnormal or inefficient movements. The challenge is differentiating normal delays from those that signal potential developmental problems.1 For example, observations of generations of children tell us that walking is initiated at approximately 10 to 13 months, yet some infants take their first steps as early as 8 months or as late as 18 months. This type of variation occurs at all stages of child development and requires pediatric therapists to examine and provide interventions to children on a constantly changing developmental base.2 Pediatric therapists play a crucial role in determining the absence of movement components that may impede the accomplishment of developmental milestones or functional goals for a child. In addition to child development, pediatric practice requires the therapist to acquire specific knowledge in basic areas ranging from child psychology to motor learning. The cognitive strategies and learning methods of adults are generally functionally oriented toward work, leisure, or daily living activities, whereas children learn from a different point of view—play. The pediatric PT is often found in what might be called compromising situations—hopping, rolling, tumbling—to engage and invite the child to participate in therapeutic activities. Play is the medium most used to promote therapeutic activities for young children, whereas for adolescents, therapy goals may be structured around social situations.3,4 The primary goal is to identify meaningful activities that correspond to the learning style of each pediatric client, given the age, culture, and most natural social and physical environments (Figure 12-1). Children who have health problems that require specialty or subspecialty care are often referred to as “children with special health care needs.”5,6 Pediatric therapists may provide direct or consultative therapy to these children over long periods, depending on the child’s changing needs. When caring for children with special needs, PTs collaborate closely with the family and other health professionals in designing a long-term, family-centered plan of care (Figure 12-2). This plan includes a full range of services—prevention, early identification, evaluation, diagnostics, treatment, habilitation, and rehabilitation.7 Throughout service provision, emphasis is placed on recognizing each child as part of a family system, with unique cultural characteristics that must be considered when treatment goals are designed. If the PT focuses solely on the child’s motor strengths and needs while neglecting the cultural impact of family and community factors on that child, a successful treatment outcome is unlikely. The World Health Organization (WHO) has issued an International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) that describes the impact of a person’s health condition on body functions and structures, daily activities, and social participation.8 This model describes the process of enablement and disablement on several levels: body structures and functions, activities, and participation (Figure 12-3 and Table 12-1).8 Table 12-1 Modified from International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF), Geneva, 2001, World Health Organization. When the WHO model is used as a guide for care of a child, all these factors are considered important elements in the design of a plan of care. It is important to note that the WHO framework is consistent with the American Physical Therapy Association’s Guide to Physical Therapist Practice9 and the practice model adopted by the National Center for Medical Rehabilitation Research.10 Throughout each of these frameworks, the PT addresses body structure and function, activity limitations, and participation limitations as a result of disease or injury. Another important point is that the PT can advance a child through an enabling process by addressing the body’s structural integrity so that age-appropriate movement and interactive activities can occur. In a climate of radical health care reform and shifting venues for pediatric practice, a practitioner’s understanding of the interdependence of all levels of the WHO model is relevant and applicable to the evaluation process and success in achieving outcomes. In 1975, Congress passed the Education of All Handicapped Children Act (EHCA), Public Law 94-142. This landmark legislation has continued to shape the evolution of pediatric practice for all professional disciplines.11 The main premise of the EHCA was that all children from ages 6 to 21 years, regardless of disability, were entitled to free and appropriate public education. This premise set the basic framework for policy and standards, which were amended in 1986 with passage of Public Law 99-457 (Amendments to the EHCA) and again in 1991 and 2004 with reauthorizations as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA).12,13 These amendments provide distinct policy for children from birth until 3 years and from 3 through 5 years of age.14 Although the states must abide by a set of regulations for implementing services, each state can establish some of its own regulations, such as the inclusion of children who are “at risk” or transitioning from early intervention to school-based services.13 Specific language in the amendments stipulates the concept of collaboration between parent and professional, as well as a family-centered focus throughout the process of pediatric examination, intervention, and care coordination. In addition, this legislation sets forth policy guidelines requiring that children be cared for in their “least restrictive” environment or in “natural” environments ranging from home to daycare centers as optimal sites for physical therapy intervention (Figure 12-4).12,13,15 Autism is a severe disorder in the group of conditions called pervasive developmental disorders (PDDs).16 PDDs are characterized by impairments in social interactions with others and communication skills, commonly accompanied by the presence of unusual activities and interests such as repetitive behaviors, stereotypies, and poor play skills. A diagnosis of autism is most typically made when the child has onset of symptoms before the age of 3 years and meets six of the 12 criteria identified in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV).17 PDDs are currently understood to be brain-based neurologic disorders of multiple origins and can coexist with other developmental disabilities including intellectual disabilities and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).18 Although the primary impairments for these children are in the communication, social, and behavioral domains, there can be associated motor and sensory impairments for which physical and occupational therapy can provide intervention and support. Examples include sensory integrative disorders, balance and coordination deficits, and motor development delay. These limitations in activities are influenced in some children with autism by attention deficits and tendency to perseverate on favorite objects and activities. The primary role of the physical or occupational therapist (OT) is to provide encouragement and maximize opportunities for age-appropriate movement experiences, and to address the sensory issues exhibited by many that can interfere with purposeful interactions with people and the environment. PTs and OTs work in cooperation with the other members of the medical and educational team to provide a consistent behavioral program designed for the individual child’s needs. One of many rheumatic diseases, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA) is characterized by inflammation of connective tissue manifested as a painful inflamed joint (arthritis). The cause of JRA is unknown, although genes associated with a variety of forms of JRA have been identified.19 Similar to other autoimmune disorders, JRA appears to be the result of complex genetic and possibly environmental exposures.20,21 JRA may be manifested in several distinct forms or subtypes, each with different characteristics. These subtypes vary in the number of joints affected, age at onset, male-to-female ratio, clinical findings, and prognosis. Signs and symptoms usually include joint pain, swelling, decreased motion, stiffness, and muscle atrophy. The majority of children in whom JRA is diagnosed lead active lives with the assistance of medications, therapeutic exercise, and specialized care programs. It is generally believed that an interdisciplinary team including parents, a pediatric rheumatologist, a nurse, a psychologist, a PT, and an OT is best for total care coordination. The primary role of the PT is to assist in preventing deformity and improving the overall quality of life for the child. The primary focus is generally the child’s musculoskeletal needs, with special emphasis on needs that affect function. PTs also play a role in exercise prescription, because physical conditioning has been shown to increase functional abilities without exacerbating JRA.22 Individualized goals are collaboratively planned to address posture, strength, mobility, and joint motion within the child’s daily functional routine. Including the parent and child in decisions regarding education and instruction is vital because the home is where the majority of the child’s goals will be reinforced.23 Scoliosis is characterized by a lateral curvature of the spine. The curve may vary in severity from mild to severe. Scoliosis may be idiopathic (of unknown origin), neuromuscular, or congenital (present at birth). Scoliosis is now detected more frequently because of school-based screening programs and is noted by asymmetry of the shoulders, breasts, and pelvis, among other factors. Treatment involves a wide range of external or internal fixations. Studies have shown that electrical stimulation had no effect on prevention of idiopathic curve progression; therefore its use in clinical practice is not supported.24 Exercise assists in reducing back pain and improving range of motion. For children with mobility limitations, positioning in appropriate seating systems is crucial to reduce the risk of scoliosis. Developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) results from abnormal development of the structures surrounding the hip joint, such that the head of the femur can move into and out of the hip socket. The cause of DDH is unknown, but the disorder is thought to be related to a number of factors such as maternal hormonal changes during pregnancy, in utero positioning, increased birth weight, multiple gestation pregnancy, birth trauma, and family history of DDH.25 The incidence of DDH is unclear because debate exists over methods of screening and classification.26–28 Treatment involves manual or surgical return of the femoral head to the hip socket and stabilization with splints or casts, depending on the degree of impairment and age of the child. Intensive postsurgical exercise protocols are required for full range of joint motion, muscle strength, and function to be achieved. Children with spina bifida and certain forms of cerebral palsy (CP) are more prone to DDH and are monitored through regular physical examinations. A common and severe bone disorder of genetic origin, osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) affects the formation of collagen during bone development, leading to frequent fractures during the fetal or newborn period.29 The fetal form of OI is associated with high mortality, whereas the infantile form is less severe, with increased vulnerability to frequent fractures of the long bones in early childhood. Children with OI are identified through characteristic limb deformities, dental abnormalities, stunted growth, scoliosis, loose ligaments, and an unusually shaped skull. Treatment of fractures and prevention of deformity through positioning and joint range-of-motion exercises are the major foci of intervention, as well as gentle exercise after postsurgical healing.29,30 In Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), females do not manifest symptoms but are carriers of the disease, whereas males do manifest symptoms. Boys with DMD usually develop normally until 3 to 5 years of age, when progressive lower extremity muscle weakness and wasting become apparent and are combined with enlarged yet weak calf muscles and tight heel cords. Associated complications include muscle contractures, spinal curvature (scoliosis), and wheelchair dependence by 10 to 12 years of age. Progressive weakness, pneumonia, and cardiac abnormalities reduce the life span of persons with DMD.31 Ongoing clinical trials have reported improved outcomes, including prolonged independent and assisted walking, in individuals who have been on long-term steroid therapy.32 The use of nighttime ventilation may increase the life span for an individual with DMD to as much as 25 years.31,33,34 Developmental effects of this type of muscular dystrophy may include mild mental retardation or learning disabilities, low muscle tone, and delays in attainment of motor milestones.35 Activity limitations are closely associated with muscle strength and cognitive level.36,37 Given the increased life span for those individuals who benefitted from steroid therapy and/or nighttime ventilation, emphasis on transition services and preparation for college, work, driving, and independent living are all important considerations in overall patient management. Symptoms of spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) include severe muscle weakness in infancy and progressive respiratory failure. Children with the infantile form of SMA have a decreased life span, whereas children with the juvenile form have a longer (but less than normal) life span and require aggressive physical therapy and orthopaedic management.38,39 A neural tube defect results from failure of the neural tube to close completely during the first month of gestational development. Although the cause of the neural tube defect is unclear, some hypotheses suggest that this impairment may be a result of genetic expression in combination with factors in the fetal (maternal) environment.40 Environmental factors such as hyperthermia, maternal nutritional deprivation, and valproic acid have been suggested, and maternal folate deficiency has been determined to exert a strong influence.41–43 Studies have shown that daily folic acid supplementation (400 mg/day) can reduce the incidence of new cases of neural tube defects by at least 50%.41 Recent advances in surgical techniques have led to attempts to close the neural tube in utero rather than delaying intervention until the infant has been born. Outcome studies regarding the benefit of this experimental procedure are under way.44 Children in whom developmental coordination disorder (DCD) is diagnosed may have a wide range of dysfunctions, including gross or fine motor coordination problems such as awkward running, frequent falling, slow reaction times, immature balance reactions, poor handwriting, and difficulty with activities of daily living such as dressing.45–47 Children with DCD frequently have psychosocial problems in addition to their motor dysfunctions. The cause of DCD is unknown but may be related to prenatal or perinatal insults to the central nervous system or damage to the neurotransmitter and receptor system.47 DCD is more commonly diagnosed in children with ADHD and learning disabilities than in children without these conditions. Treatment for DCD includes comprehensive management of all the child’s areas of difficulty.45 Recent research on interventions for children with DCD offers encouraging results related to improved quality of life and reduced health risks that can be associated with a sedentary lifestyle of children with DCD.48 Down syndrome is a congenital developmental disability caused by the presence of an extra copy of chromosome 21; it is also called trisomy 21. Routine prenatal care commonly includes screening for Down syndrome. New ultrasound techniques have increased the ability to prenatally diagnose Down syndrome in the first and second trimesters.49 A child with Down syndrome is characterized by low muscle tone, a flat facial profile, upwardly slanted eyes, short stature, varying levels of intellectual disability, slowed growth and development, a small nose with a low nasal bridge, and congenital heart disease (e.g., atrial or ventricular septal defects).50–52 Associated complications may include instability of the first and second vertebrae, lax ligaments, seizures, leukemia, and premature senility.53–57 The combination of these features is often manifested as deficiencies in balance, stability, and agility across many tasks and environmental contexts. Developmentally, a child with Down syndrome has decreased muscle tone, which improves with age. This abnormality is accompanied by loose ligaments that result in increased range of joint motion. The rate of developmental progress decreases with age in individuals with Down syndrome.57–59

Physical Therapy for Pediatric Conditions

Describe the relationship among body structure, functional abilities, and activity limitations as presented by the World Health Organization

Describe the relationship among body structure, functional abilities, and activity limitations as presented by the World Health Organization

Describe the impact of federal legislation on the delivery of physical therapy services to children

Describe the impact of federal legislation on the delivery of physical therapy services to children

Describe the general features of common pediatric conditions seen by a physical therapist or physical therapist assistant

Describe the general features of common pediatric conditions seen by a physical therapist or physical therapist assistant

Describe aspects of the patient/client examination that are unique to pediatric clients

Describe aspects of the patient/client examination that are unique to pediatric clients

Describe the general features of four physical therapy treatment approaches for pediatric clients

Describe the general features of four physical therapy treatment approaches for pediatric clients

General Description

Disablement Classification

Characteristics

Interaction Level

Impairment of body structures and body functions

Child

Activity limitations

Child–daily environment

Participation restriction

Child–community and society

Impact of Federal Legislation

Common Conditions

Developmental Disorders

Orthopaedic Disorders

Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis

Scoliosis

Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip

Osteogenesis Imperfecta

Neuromuscular and Genetic Disorders

Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy

Spinal Muscular Atrophy

Neural Tube Defects

Developmental Coordination Disorder

Down Syndrome

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Physical Therapy for Pediatric Conditions