Fig. 1

Referred muscle pain from somatic and visceral sources (From Giamberardino M in Encyclopedia of Pain, SpringerReference, 2013 [23])

Anatomy of the Pelvic Floor

The pelvic floor complex consists of muscles, ligaments, and fascia that form a multilayered support for the inferior pelvis in order to perform three important functions: supportive, sphincteric, and sexual [9]. It is composed of visceral pelvic fascia and pelvic diaphragm, the urogenital and anal triangles with superficial and deep genital muscles, and the sphincters of the urethra and anus. The pelvic diaphragm muscles can be subdivided into the levator ani group, the coccygeus, and the obturator internus. The perineum can be divided into the urogenital and anal triangle regions, with the perineal body the anchor point between them. Superficial external genital muscles include the external anal sphincter in the anal triangle and the superficial transverse perineal, bulbocavernosus, and ischiocavernosus in the urogenital triangle. In part they form a figure of eight around the front passages (vaginal and urethral) and the back passage, the anus [9]. See Fig. 2. The interaction between the pelvic floor muscles and the supportive ligaments is critical to pelvic organ support [10]. The urogenital diaphragm (the perineal membrane) is deeper in the urogenital triangle. It is anterior to and more superficial than the pelvic diaphragm and oriented transversely with fascia and muscle that spans from the ischiopubic rami bilaterally. It consists of the striated urogenital sphincters: sphincter urethrae, compressor urethrae, and urethrovaginal sphincter muscles [9]. Female urethral sphincters include the striated rhabdosphincter sphincter (the sphincter urethrae) and two distal urethral sphincters, the intrinsic sphincter, and external sphincters. The levator ani and the compressor urethrae muscles assist the sphincters in urethral closing. The psoas muscle invests into the pelvic fascia, affording a direct biomechanical link between function or psoas dysfunction and PFD. See Fig. 3.

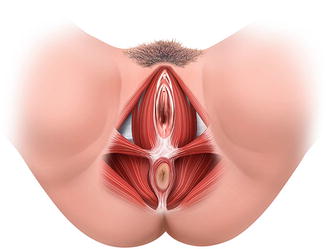

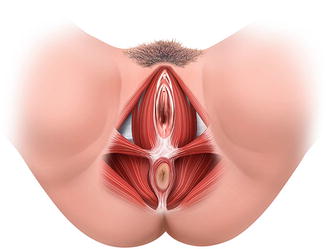

Fig. 2

Muscles of the pelvic floor (With permission from PIXOLOGICSTUDIO/Science Source) (Female pelvic floor. Computer artwork of the female pelvic floor muscles seen from below. The muscles maintain continence as part of the urinary and anal sphincters. At center top is the clitoris, with the urethra, vagina and rectum below it. The bulbospongiosus muscle, surrounds the urethra and vagina. The external anal sphincter controls the anal opening. Either side of the anus are the levator ani, which support the pelvic organs and surrounds the anus and vagina. Running across center is the deep transverse perineal muscle, which also supports the pelvic organs)

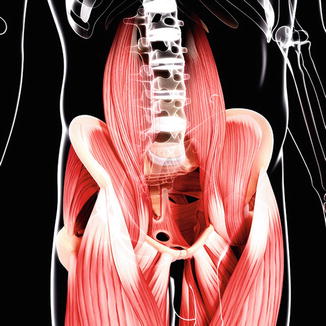

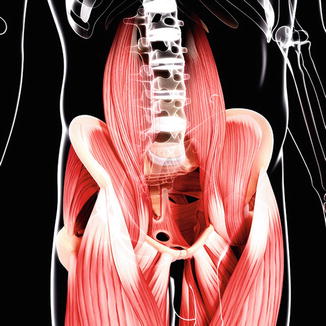

Fig. 3

Psoas muscle (With permission from PIXOLOGICSTUDIO/Science Source) (Human hip musculature, computer artwork)

The pelvic walls are formed by bones and ligaments partly lined with muscles and covered with fascia. The anterior pelvic wall is a shallow wall formed by the posterior surfaces of the pubic bones and symphysis pubis. The posterior pelvic wall is a more extensive wall, consisting of the sacrum, coccyx, and piriformis muscle. The lateral pelvic wall is a component of the pelvis formed by part of the innominate bone, the obturator foramen, the sacrotuberous and sacrospinous ligaments, and the obturator internus muscle and fascia. The inferior pelvic wall, or pelvic floor, consists of the levator ani muscles, coccygeus, and pelvic fascia. It is accessible to palpation only through internal vaginal (women) or rectal (women and men) examination [2].

Bones and Ligaments That Form the Pelvic Floor

The pelvis is a ring and the base of support for the upper and lower torso and extremities. Located in the posterior pelvic ring are the sacroiliac joints. These are synovial joints inferiorly, have anterior and posterior capsules, and are surrounded by ligaments: the anterior sacroiliac ligament, the dorsal longitudinal sacroiliac joint (SIJ) ligament, and the interosseous sacroiliac ligaments, which could contribute to posterior pelvic pain [2]. Ligaments extrinsic to the SIJ but that contribute to posterior pelvic pain include the iliolumbar and sacrotuberous ligaments. The iliolumbar ligament absorbs and distributes forces from the lumbar spine and ilium. The sacrotuberous ligament absorbs and distributes forces from the lower extremity through direct and fascial attachments to the hamstrings and thoracodorsal fascia.

The symphysis pubis is a cartilaginous joint between the two pubic bones. It is surrounded by ligaments that allow subtle motion in frontal, inferior, and superior sheer motion and rotational planes. This joint is subjected to substantial mechanical stresses during pregnancy. Muscles from the abdomen (rectus abdominis) and lower extremities (adductors) insert or originate at the pubis assisting with load transfer, providing a direct pathway for myofascial overload and pain referral patterns from the pelvis cephalad to the abdomen or caudad to the lower extremities. Lastly the sacrococcygeal joint is a cartilaginous joint that is joined by ligaments. Much movement is possible at this joint, although this varies among individuals [2]. The joint can be palpated both externally and internally, with internal palpation via the rectum affording the best assessment of pain, mobility, and alignment.

Nerves to the Pelvic Floor

The lumbosacral trunk passes into the pelvis and joins the sacral nerves as they emerge from the anterior sacral foramina. From a clinical perspective, the important nerve branches associated with clinical syndromes at or near the pelvic floor include sciatic, obturator, femoral, lateral femoral cutaneous, and pudendal nerve [2]. The clinical anatomy of the pudendal nerve and its branches make it prone to damage during complicated vaginal childbirth and surgical interventions. The pudendal nerve arises from the sacral plexus from the ventral branches S2, S3, and S4. It supplies sensation to the external genitalia and motor function to the urinary and external anal sphincters and muscles responsible for ejaculation in men and orgasm in both genders. Because of its complex and comprehensive function, the pudendal nerve is implicated in PFD related to pain, incontinence, and sexual dysfunction [2]. Recent studies have shown that the levator ani muscles were innervated by a nerve that originated from S2–4 that branches at a point proximal to the ischial spine (before the pudendal nerve roots reach the sacrospinous ligament) and then innervates the levator ani muscles on their pelvic surface [11]. As noted previously, the pelvic floor reflex innervation affords wide representation of referred pain from primary pain generators in visceral and somatic structures via mechanisms such as activation of peripheral reflex arcs and central hyper excitability. Pelvic floor hypertonic dysfunction can present with dysfunction of the viscera that are controlled by the pelvic floor and may present as a primary pain generator or solely as a component of a chronic pain syndrome [12].

Understanding the Presentation of Arthroscopic and Open Hip Joint Preservation Surgery Patients with Pelvic Floor Dysfunction

As noted earlier in the chapter, muscles involved in hip function often respond to injury or dysfunction by guarding and may even rest in a contracted or overactive position. While this may be easily recognized on history and physical examination in muscle that attached externally to the hip and pelvic girdle, one must entertain a high level of suspicion for pelvic floor dysfunction in certain patients. For example, external muscle guarding in the gluteus medius muscle can present with pain with ipsilateral side lying, be associated with greater trochanter bursitis, and present with an antalgic gait. This would likely be easily recognized by physician, physician extender, or physical therapist and addressed efficiently. If the health-care provider does not include the entire array of muscles that provide stability and mobility to the hip joint as part of the comprehensive assessment of the arthroscopic and open hip joint preservation surgery patient with persistent pain and/or impairments pre- or post successful surgery, they will fail at providing comprehensive care. As the old adage goes, overactive or hypertonic pelvic floor muscles have likely “seen you” but you “have not seen them.” If one were not aware that the pelvic floor muscles’ adaptation of prolonged contraction prior to surgery had perpetuated post surgery, the examiner may miss historical and physical exam findings to diagnose the pelvic floor dysfunction and offer appropriate treatment. Further, patients may not offer key historical information as they may not be aware of the link between pelvic floor symptoms and their “hip” pain . Patients with missed pelvic floor presentations often undergo additional imaging and procedures that do not shed further light on the problem and have inherent risks of radiation, medication, and other unnecessary exposures. In addition, patients presenting with certain imaging findings such as labral tears, which are sometimes asymptomatic findings, may be misdiagnosed and not receive appropriate treatment to address the primary pain generator, for example, the pelvic floor muscles, and may even undergo surgery without success in these circumstances.

Frequently, there is muscle hyperalgesia, typically proportional to the extent of the primary injury. The hyperalgesia can be associated with trophic muscle changes, including loss of muscle mass [13]. Myofascial trigger points , taut bands of muscle fibers, can develop causing local and referred pain patterns. Referred muscle pain and loss of muscle mass can compound gait abnormalities and other functional impairments, perpetuating disability.

History

To increase recognition of PFD, a more extensive review of symptoms (ROS) beyond the comprehensive orthopedic history must be obtained, querying for changes in bowel, bladder, and sexual function. These complaints provide insight into contracted pelvic floor muscles that are not relaxing properly during defecation, allowing for complete bladder emptying or causing sexual dysfunction or pain. Because of the embarrassing aspects of such complaints, it is especially important for the health-care provider to query patients about bowel, bladder, and sexual functioning symptoms directly. Reports of constipation outlasting narcotic use, painful intercourse, reduced or absent orgasm or ejaculation, inability to tolerate vaginal tampon, frequent urination, and other symptoms can be clues to hypertonic pelvic floor muscles. Patients with painful pelvic floor muscles may also report referred pain to the lower back, gluteus, groin, or lower extremities. In keeping with clinical reasoning, questions about pain onset, aggravating and relieving factors, quality and intensity, and others must be included in the complete history. Information about local patterns of hypo- or hyperalgesia can implicate associated peripheral nerve involvement.

Physical Examination

As with all orthopedic patients, the physical exam of the patient with PFD includes observation, palpation, neurological testing, joint and muscle testing, and other special tests. See Table 1 for an overview of the physical examination of the pelvic floor. The pelvic floor examination is done in addition to the complete lumbopelvic and LE examination, as directed by the patient’s history.

Table 1

Physical examination of the pelvic floor

1. Obtain verbal consent |

2. Inspect perineum and genitalia for scarring, defects, lesions, and skin changes; identify pelvic organ prolapse-rectocele, cystocele, etc. |

3. Neurological examination |

(a) Sensory exam, S2–5 light touch, pinprick |

(b) Anal wink |

(c) Tinel test – pudendal nerve

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|