Patient Selection for Hip Preservation Surgery

Jeffrey J. Nepple

John C. Clohisy

In the last decade, the diagnosis and treatment of young adult hip disease, including femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) and acetabular dysplasia, has become increasingly common (1). As our understanding of young adult hip pathology continues to improve, we are better able to identify which patients are likely to benefit from hip preservation surgery. Proper patient selection for surgery in young adult disorders is vital for the maximal success of these procedures. The most common surgical interventions in this patient population include hip arthroscopy, open surgical hip dislocation, and periacetabular osteotomy (PAO). This chapter will review patient characteristics, history, physical examination, and radiographic factors which are important to consider for hip preservation surgery. In addition, we will review factors unique to patient selection for hip arthroscopy, open surgical hip dislocation, and the Bernese PAO.

Patient Characteristics

A variety of patient factors are important to consider in the surgical treatment of young adult hip disease. This should include a general overview of the patient’s age, general health, and activity level, including any medical comorbidities, connective tissue disorder (or family history of), or tobacco use. A history of previous hip surgery or pediatric hip disease should be investigated. Information regarding any sporting activities and associated symptoms should also be noted. Details regarding sporting activities including position, sport-specific hip requirements, and occurrence of symptoms are often relevant to the pathophysiology of the hip disorder, as well as rehabilitation and postoperative return to play. FAI is strongly associated with sporting activities involving deep hip flexion, including hockey and football among others (2). Recent evidence suggests that aggressive athletic activity during adolescence may play a role in formation of the bony deformity typical of FAI (3,4,5). However, only a fraction of individuals with such deformity will develop hip pain.

Patient History

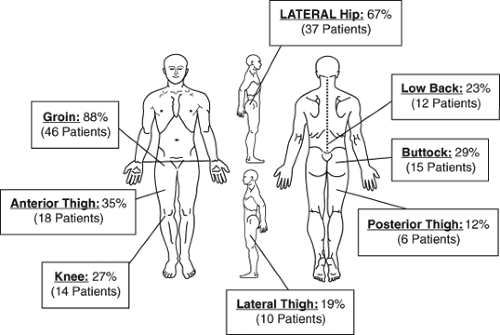

The location of pain around the hip is important to determine (6,7). Pain due to intra-articular hip pathology classically presents with anterior groin pain and may be represented by the patient demonstrating a “C-sign” around the anterior aspect of the greater trochanter. However, significant overlap including the presence of additional lateral and posterior hip pain is not uncommon (6) (Fig. 16.1). The chronicity of pain and any associated acute change should be determined. Prolonged symptoms may indicate more advanced secondary osteoarthritis. The presence of mechanical symptoms should raise concern for an unstable labral tear, chondral flap, or loose body. The classic presentation of hip dysplasia includes lateral hip pain with prolonged walking or running due to abductor fatigue. On the other hand, the classic presentation of FAI includes anterior groin pain with deep hip flexion and prolonged sitting. Nonetheless, these two disorders have substantial symptomatology overlap.

Diagnostic injections (anesthetic injections) can be extremely useful in confirming the intra-articular source of hip pain. Injections are commonly performed with ultrasound or fluoroscopic image guidance. Short-term relief of pain with activities or during provocative examination helps confirm the intra-articular origin of the pain. More equivocal responses must be viewed in the context of the patient’s presentation. Corticosteroid injection use in younger patients is controversial but may provide longer-term relief in patients attempting to avoid or delay surgery.

Physical Examination

Initial physical examination should include general body habitus, walking gait, and sitting posture. Excellent candidates for hip preservation surgery are well conditioned, active, and have a normal body mass index. Obese patients and those who are deconditioned may have a worse prognosis with hip preservation procedures. Basic neurovascular function, muscular strength, and leg length assessment

should be performed. Severely deconditioned hip musculature may indicate a need for muscle strengthening therapy prior to any consideration of surgery. Compensatory mechanisms in the extraarticular hip and pelvis musculature can result in secondary pain generators around the hip, including athletic pubalgia/osteitis pubis, hip flexor tendinitis, greater trochanteric bursitis, and sacroiliac joint pain (8). A detailed assessment of hip range of motion is extremely important in differentiating between various young adult hip disorders. In addition to diagnostic information, the hip range of motion may have treatment implications. For example, adequate range of motion must be present for the hip to tolerate acetabular reorientation. Hip flexion measurements should be performed with palpation of the pelvis to determine the point at which pelvic tilt allows for further flexion. Similarly, hip abduction should be tested until lateral tilt of the pelvis is detected. The amount of internal rotation in 90 degrees of flexion (IRF) should be determined, as well as any associated pain with testing. The impingement test can then be easily tested with the addition of hip adduction to this maneuver and is a useful screen for general intra-articular hip pathology. An IRF of less than 15 degrees is suggestive of underlying FAI. However, decreases in femoral version (femoral retroversion or decreased relative anteversion) similarly will decrease IRF. Similarly, excessive IRF greater than 45 degrees should alert the examiner to possible increased femoral anteversion. Measurements of external rotation in 90 degrees of flexion are often inversely related to IRF. However, consideration of the total arc of motion in flexion can also be useful. Increased arcs of motion are often present in patients with underlying capsular laxity whereas decreased arcs of motion may be present in individuals with severe FAI, residual childhood deformities (slipped capital femoral epiphysis and Perthes disease), or osteoarthritis. Generalized ligamentous laxity can be assessed by examination of other joints including the knee, elbow, and hand/wrist, or by the assessment using Beighton’s criteria (9). In borderline dysplastic hips with concern for structural instability, the soft tissue laxity about the hip may have important treatment ramifications. Soft tissue laxity combined with borderline structural instability may be an indication for osteotomy over an isolated arthroscopic procedure.

should be performed. Severely deconditioned hip musculature may indicate a need for muscle strengthening therapy prior to any consideration of surgery. Compensatory mechanisms in the extraarticular hip and pelvis musculature can result in secondary pain generators around the hip, including athletic pubalgia/osteitis pubis, hip flexor tendinitis, greater trochanteric bursitis, and sacroiliac joint pain (8). A detailed assessment of hip range of motion is extremely important in differentiating between various young adult hip disorders. In addition to diagnostic information, the hip range of motion may have treatment implications. For example, adequate range of motion must be present for the hip to tolerate acetabular reorientation. Hip flexion measurements should be performed with palpation of the pelvis to determine the point at which pelvic tilt allows for further flexion. Similarly, hip abduction should be tested until lateral tilt of the pelvis is detected. The amount of internal rotation in 90 degrees of flexion (IRF) should be determined, as well as any associated pain with testing. The impingement test can then be easily tested with the addition of hip adduction to this maneuver and is a useful screen for general intra-articular hip pathology. An IRF of less than 15 degrees is suggestive of underlying FAI. However, decreases in femoral version (femoral retroversion or decreased relative anteversion) similarly will decrease IRF. Similarly, excessive IRF greater than 45 degrees should alert the examiner to possible increased femoral anteversion. Measurements of external rotation in 90 degrees of flexion are often inversely related to IRF. However, consideration of the total arc of motion in flexion can also be useful. Increased arcs of motion are often present in patients with underlying capsular laxity whereas decreased arcs of motion may be present in individuals with severe FAI, residual childhood deformities (slipped capital femoral epiphysis and Perthes disease), or osteoarthritis. Generalized ligamentous laxity can be assessed by examination of other joints including the knee, elbow, and hand/wrist, or by the assessment using Beighton’s criteria (9). In borderline dysplastic hips with concern for structural instability, the soft tissue laxity about the hip may have important treatment ramifications. Soft tissue laxity combined with borderline structural instability may be an indication for osteotomy over an isolated arthroscopic procedure.

Radiographic Factors

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree