29

Patellar Tendinosis

The terms patellar tendinitis and tendinosis have, unfortunately, been used interchangeably. Tendinitis suggests histopathologic features of inflammatory cells infiltrating normal tendon substance and does not adequately relate the chronicity of the condition. Tendinosis refers to the degeneration of the substance of the patellar tendon from repetitive use. This is the entity most often referred to when using the term tendinitis.1 Patellar tendinitis was called “jumper’s knee” by Blazina et al2 in 1973. This descriptive designation reflects the types of athletes at risk. Participants in sports such as volleyball or basketball that require sudden, repetitive, ballistic jumping may develop patellar tendinosis.3 Most patients are young, between 18 and 25, but it may occur at all ages.3 The athlete complains of pain when jumping that is localized to the anterior aspect of the knee, usually at the inferior pole of the patella.3 The severity of the disease can be graded based on the extent of the symptoms as described by Blazina et al. Physical examination confirms the diagnosis when the athlete has tenderness at the inferior pole of the patella with the knee in full extension. The pain usually dissipates with the knee in flexion.3, 4 Imaging studies such as magnetic resonance imaging may be helpful if the diagnosis is equivocal. But plain radiographs and bone scan offer little to aid in the diagnosis.5

Several studies have looked at the precise pathology involved in patellar tendinosis. It is theorized that the patellar tendon sustains repeated microtears of the undersurface with repetitive jumping activities.6 This zone of injury is replaced with glycosaminoglycans and chondroitin sulfate.7 Other histologic changes include infiltration of blood vessels, fibroblast proliferation, and hemosiderin deposition.5

Surgical Indications and Other Treatment Options

Blazina et al2 divided patellar tendinosis into three clinical stages. In stage 1, patients have symptoms only after activity. In stage 2, symptoms develop during and after activity, but these symptoms are not debilitating. In stage 3, patients have symptoms during and after activity which adversely influences their performance.8 The first two stages are often treated successfully with conservative therapy. Conservative therapy entails rest, cryotherapy, quadriceps strengthening, hamstring stretching, and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs.4, 8 Other modalities may be added such as ultrasound, but steroid injections are not an accepted form of treatment.4, 8 If the symptoms persist for 6 months or more, do not respond to conservative therapy, or worsen to stage 3, the patient may then require surgical intervention.3, 8

Surgical Techniques

Open Technique

The patient is brought to the operating room without any anesthesia. The patient is transferred to the operating room table, and the extremity is examined to confirm the point of maximal tenderness. The patient is then placed under general anesthesia. A lateral post may also be placed at the level of the midthigh, where a tourniquet is wrapped. A leg holder is not used. The extremity is then prepped and draped in sterile fashion.

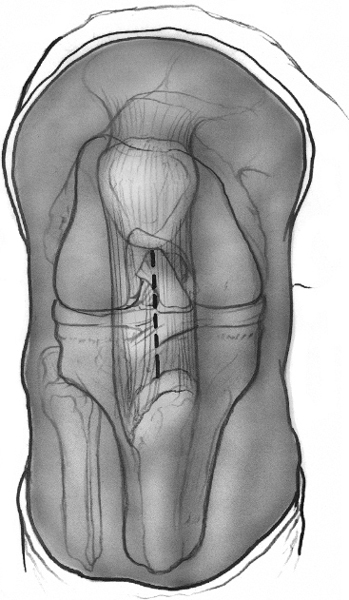

A longitudinal incision is made in the midline extending from the inferior pole of the patella to the superior aspect of the tibial tubercle (Fig. 29-1). Due to the mobility of the skin beneath the dermal layer, a shorter incision may be used. Sharp dissection is used to expose the paratenon. The paratenon is incised parallel with the incision and reflected medially and laterally to expose the tendon. The tendon is examined near the inferior pole of the patella for an area of discoloration, degeneration, or firmness. Anterolateral and anteromedial portals are then placed inside the incision, fanking the patellar tendon. The joint is examined for any intraarticular pathology.

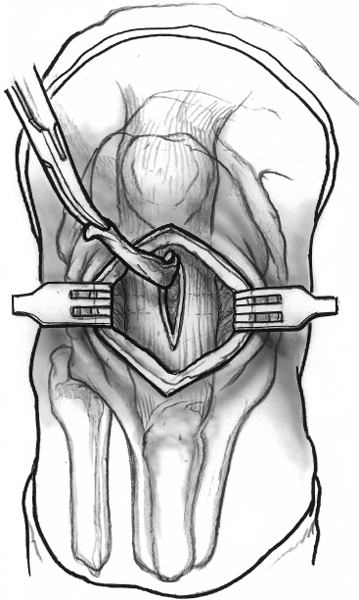

When the arthroscopy is complete, the area of pathology is once again identified. A longitudinal incision is made on the medial side of the abnormal tendon extending 2 cm distally. The section of tendon is examined to confirm a myxoid appearance or firmness to palpation. A second longitudinal incision is made parallel to the first and flanking the area of degeneration. The distance between the two incisions should be 3 to 5 mm and certainly less than one third the width of the tendon. The two incisions converge distally to form an ellipse, and the intervening tendon is excised (Fig. 29-2).

Figure 29-1 Drawing of the anterior aspect of a flexed knee. The patellar tendon borders are outlined. The vertical incision is made in the midline of the tendon extending proximally from the inferior pole of the patellar tendon to the tubercle. The incision may be shorter, taking advantage of the mobility of the skin in this area.

The remaining tendon and the excised tendon should be examined to confirm the complete removal of the degenerative tissue. The wound is irrigated, and the paratenon is closed using a running suture. If the excised region is large, one or two loose approximating sutures may be placed across the defect. The subcutaneous tissue is closed prior to skin closure.

Figure 29-2 Drawing of the anterior aspect of the knee after skin incision and reflection of the paratenon. The diseased portion of the tendon is excised as an ellipse.

Arthroscopic Technique

The surgeons at this institution do not use arthroscopic techniques because of the good results and low morbidity of the open technique. However, several authors have published techniques with good results using arthroscopic debridement.9 One technique describes placing the arthroscope in the superolateral portal while placing the shaver inthe anterolateral portal. The fat pad is debrided sufficiently to allow visualization of the proximal diseased portion of the tendon. This is debrided to normal tissue using the shaver.9

Tips and Tricks

If the diagnosis is in question or if there is concern over the precise region of pathology, the patient may help localize the site intraoperatively. Prior to putting the patient to sleep, the surgeon examines the knee to find the point of maximal tenderness. This area may be marked with a marking pen. The skin only is infiltrated with lidocaine under sterile conditions. The leg may then be prepped and draped with the patient awake. A skin incision may be made and the tendon examined for the point of maximal tenderness. This region is infiltrated with lidocaine. Dissipation of the pain confirms the region of pathology. The patient is then put to sleep prior to arthroscopy and excision of the pathologic region.

A sandbag may be placed at the foot of the bed to allow a knee flexion angle of 80 degrees when the foot abuts the sandbag. This may help with positioning during the excision. It is often easier to palpate the abnormal firm region of the tendon with knee extended, but excision is facilitated by some tension on the tendon with knee flexion.

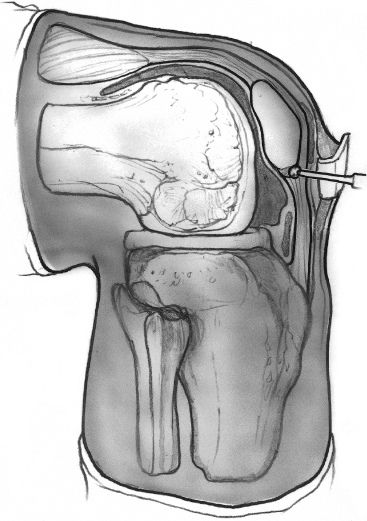

Examine the inferior pole of the patella. If it appears to abut the area of degenerative tissue, it should be excised using a rongeur and curette (Fig. 29-3). Part of the success of the procedure involves neovascularization of the tendon. This may be enhanced by drilling the inferior pole of the patella.8

If the area of degeneration is difficult to locate, vertical tenotomies may be performed in the tendon to compare regions of the tendon. The area of degeneration is usually in the middle or medial aspect of the tendon; therefore, this area should be inspected first.8 The vertical tenotomies may also enhance neovascularization.

As in most procedures, the postoperative rehabilitation is nearly as important as the technical aspects of the procedure. The patient should resume a supervised quadriceps strengthening and hamstring stretching protocol.

Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Recognition of the region of degenerative tendon is essential. The degenerative tendon may appear thickened or fibrotic. Often, this is most easily identified first by palpation. Once a tenotomy is made, the intratendinous substance may be visualized and appear gray with absence of the healthy longitudinal fibers of the tendon (Fig. 29-4).

The region of pathology may be difficult to localize, particularly if the surgeon is not familiar with the gross appearance of tendinosis. In this case, consider keeping the patient awake without anesthesia as described above.

Figure 29-3 Drawing of a lateral view of the knee demonstrating the possible impingement of the inferior pole of the patella on the posterior aspect of the proximal patellar tendon. This may be excised or drilled to prevent further impingement and promote neovascularization to prevent recurrence of the degeneration.

Figure 29-4 Intraoperative photograph of the patellar tendon after partial excision of the diseased tendon. Some abnormal tendon, yet to be excised, highlights the transition from normal longitudinal tendon fibers to myxoid tissue lacking any longitudinal organization.

Conclusion

Patellar tendinosis is frequently treated successfully with nonoperative management. A patient must first undergo an adequate trial of rehabilitation, which may require up to 6 months.3 However, if symptoms persist in the face of adequate rehabilitation and the symptoms interfere with athletic participation, surgical intervention yields very good results. Surgical outcomes are better for younger patients with a shorter duration of symptoms.7 Arthroscopic and open procedures yield similar outcomes when assessing symptoms, sports success, return to playing time, and knee scores.9 In Coleman et al’s9 study, only 50% of athletes return to their preinjury level of performance. However, most other studies yield much better results, with 80 to 90% of athletes returning to play by 6 months to a year regardless of the duration of preoperative symptoms or level of play.3, 4, 8

References

1 Maffulli N, Khan KM, Puddu G. Overuse tendon conditions: time to change a confusing terminology. Arthroscopy 1998;14:840–843

2 Blazina ME, Kerlan RK, Jobe FW, Carter VS, Carlson GJ. Jumper’s knee. Orthop Clin North Am 1973;4:665–678

3 Panni AS, Tartarone M, Maffulli N. Patellar tendinopathy in athletes. Outcome of nonoperative and operative management. Am J Sports Med 2000;28:392–397

4 Griffiths GP, Selesnick FH. Operative treatment and arthroscopic findings in chronic patellar tendinitis. Arthroscopy 1998;14:836–839

5 Green JS, Morgan B, Lauder I, Finlay DB, Allen M, Belton I. The correlation of bone scintigraphy and histological findings in patellar tendinitis. Nucl Med Commun 1996;17:231–234

6 Pierets K, Verdonk R, De Muynck M, Lagast J. Jumper’s knee: postoperative assessment. A retrospective clinical study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 1999;7:239–242

7 Benazzo F, Stennardo G, Valli M. Achilles and patellar tendinopathies in athletes: pathogenesis and surgical treatment. Bull Hosp Jt Dis 1996;54:236–240

8 Popp JE, Yu JS, Kaeding CC. Recalcitrant patellar tendinitis. Magnetic resonance imaging, histologic evaluation, and surgical treatment. Am J Sports Med 1997;25:218–222

9 Coleman BD, Khan KM, Kiss ZS, Bartlett J, Young DA, Wark JD. Open and arthroscopic patellar tenotomy for chronic patellar tendinopathy. A retrospective outcome study. Victorian Institute of Sport Tendon Study Group. Am J Sports Med 2000;28:183–190

< div class='tao-gold-member'>