5

Paronychia

Sam Moghtaderi and Kevin D. Plancher

History and Clinical Presentation

A 34-year-old, right hand dominant woman presented to her physician complaining of a red, tender area surrounding the nail of the third finger of her right hand. She had received a manicure 3 days prior to the onset of symptoms.

Physical Examination

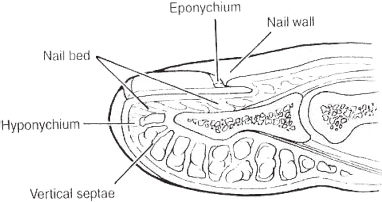

The periungual areas of the affected digit appeared erythematous and swollen, and were tender to palpation over the radial paronychial fold and the eponychium (Fig. 5–1). There was also elevation of the proximal nail bed with pus extruding from below.

Diagnostic Studies

The diagnosis of paronychia is generally clinical, and does not require any diagnostic studies.

PITFALLS

- Must differentiate from herpetic infections, for which incision and drainage (I&D) is typically contraindicated

- In making incisions, care must be taken to avoid damage to nail matrix

- Nonsurgical treatments typically not effective for chronic paronychia

PEARLS

- Paronychia is the most commonly seen infection of the hand

- Warm soaks and antibiotics effective if there is no drainage or fluctuance

- Eponychial marsupialization for chronic paronychia; also remove nail if signs of involvement

Differential Diagnosis

Herpetic whitlow

Acute paronychia

Chronic paronychia

Diagnosis

This patient’s presentation is typical of acute paronychia, an infection of the soft tissue folds surrounding the fingernail. The clinical presentation initially consists of localized tenderness of the paronychial region, with subsequent erythema, swelling, and fluctuance (Fig. 5–2). Frank drainage and elevation of the nail plate are also seen.

Figure 5–1. Schematic anatomic drawing of nail complex and its components.

Figure 5–2. Acute paronychia, with characteristic erythema and swelling.

Chronic paronychia are persistent, indurated infections of the eponychium, and present somewhat differently from acute paronychia. It is typically seen in people whose hands are chronically exposed to water with detergents and alkali, such as cleaning workers, bartenders, and kitchen staff. The etiology is thought to include an initial bacterial infection, typically followed by superinfection and colonization of the eponychium with a fungus such as Candida albicans. There is subsequent episodic inflammation and drainage, as well as a fibrosis and thickening of the eponychium secondary to the chronic low-grade inflammatory response. The patient presents with less severe erythema and fluctuance than acute paronychia, and typically does not report as much localized tenderness. A typical sign of chronic paronychia is the appearance of longitudinal grooves on the dorsal surface of the nail plate, secondary to the long-term damage to the germinal tissues in the eponychium.

Both acute and chronic paronychia have been noted with an increased incidence in diabetics, immunocompromised patients, and those receiving anti-retroviral therapy.

The most important entity to distinguish from paronychia in the differential diagnosis is herpetic whitlow, a self-limited viral infection of the fingertips caused by the herpes simplex virus. It is transmitted by skin-to-skin contact, and is often seen in medical and dental personnel, as well as in children. As with paronychia, herpetic whitlow may also present with swelling and erythema, though typically patients have disproportionately greater pain than in the case of bacterial infections. Vesicles are also seen, containing fluid that may be clear or turbid, but is never purulent. The diagnosis is usually made clinically, though it is possible to confirm it by use of a Tzanck prep or viral culture. It is important to distinguish herpetic whitlow from bacterial infections, as a surgical incision for the former can lead to complications involving the entire digit or systemic spread, and is contraindicated.

Nonsurgical Management

Nonsurgical treatment of an acute paronychia should be attempted only in the earliest stage, where the infection has not progressed to more than a mild localized erythema and swelling. In such cases, a regimen consisting of an oral antibiotic with Staphylococcus coverage (e.g., dicloxacillin 250 to 500 mg po q6h), along with warm saline soaks and rest, may be adequate. Typically, however, by the time the patient presents to a physician, there is already abscess formation and fluctuance requiring drainage.

Conservative treatment of chronic paronychia by use of topical or systemic antibiotic and antifungal agents has almost universally been unsuccessful. It is thought that the process of fibrosis and chronic injury in the eponychium leads to a diminished vascular supply and decreased delivery of such drugs.

As previously stated, herpetic whitlow should generally be treated conservatively and typically runs a self-limited course of ∼21 days. A notable exception is when bacterial superinfection is seen along with an abscess. In such cases the abscess may be carefully drained, with systemic acyclovir administered to reduce the likelihood of complications.

Surgical Management

The goal of surgical intervention for a paronychia is to allow a thorough drainage of the purulent collection. At the same time, however, it is imperative that invasion of the nail bed be kept to a minimum to avoid future growth deformities. All of the procedures described may typically be performed under a digital block anesthesia.

In cases where there is only involvement of one of the lateral nail folds, a true skin incision is not necessary. A No. 11 or No. 15 blade is used to completely lift the paronychium from the nail plate, opening the abscess in the nail fold and allowing drainage. Care must be taken to direct the sharp edge of the scalpel toward the paronychial fold and away from the nail bed, to avoid an injury to the nail matrix that may result in scarring or growth deformities. If there is any involvement of the nail bed, it is best also to remove the affected side of the nail plate, using a Freer elevator to gently separate the lateral third of the nail from the nail bed, and then using a small pair of scissors to make a longitudinal cut and remove the nail plate.

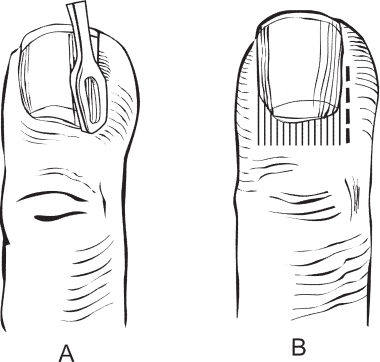

When there is involvement of the eponychium and proximal nail in addition to the lateral fold, a single incision is made beginning at the midpoint of the paronychial fold and proceeding proximally through the eponychium to reach the base of the nail. The soft tissues are elevated, and the proximal third of the nail is bluntly separated and excised with scissors (Fig. 5–3). In severe cases where a runaround or horseshoe infection involves both sides of the finger, a similar incision is made on the opposite side as well, and the entire eponychium is elevated.