7

Osteochondritis Dissecans Repair

Osteochondritis dissecans (OCD) develops when the blood supply to an area of subchondral bone is interrupt ed. Without spontaneous healing, the bone and adjacent cartilage fragments separate and become loose bodies.

Patients present with a vague, poorly localized aching pain typically of several months’ duration. They also complain of stiffness and activity-related swelling. Symptoms typically worsen with increasing activity as stable lesions detach, causing catching and locking. On physical exam, Wilson’s sign is a specific test for medial femoral condyle lesions.1 The knee is flexed to 90 degrees with the tibia internally rotated. The knee is then slowly extended. A positive test is defined by re-creating the patient’s symptoms with the knee in 30 degrees of flexion as the tibial spine abuts the medial femoral condyle. Externally rotating the tibia should alleviate the discomfort.

Surgical Indications and Other Options

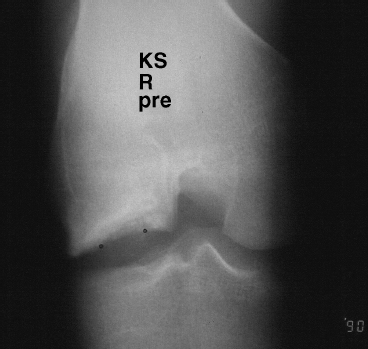

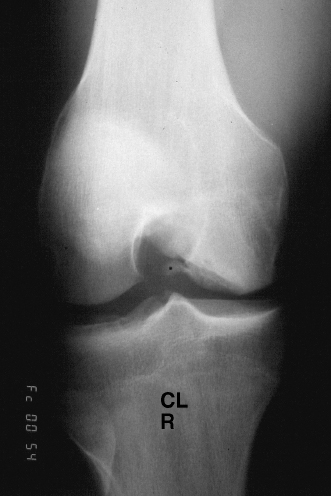

The treatment of OCD lesions is based on the age of the patient and the stage of the lesion.2 Stage I lesions are defined as not being visible on plain radiographs. Stage II lesions are defined as visible fragments that are still attached presumably by the overlying articular cartilage (Fig. 7-1). Stage III lesions are unattached lesions (Fig. 7-2) that are not displaced. Stage IV lesions are displaced fragments (Fig. 7-3).

Nonoperative treatment is reserved for skeletally immature patients or those near maturity with stable lesions (stage I or II). The physician can expect that 50% of stable lesions in young, compliant patients with open growth plates will heal in 10 to 18 months.3 Conservative treatment is based on protective weight bearing. Knee braces can be used, but knee range of motion and strength must be maintained. Casting is reserved only for the noncompliant patient because it leads to stiffness, atrophy, and cartilage degeneration.4 After 6 to 8 weeks of protective weight bearing and only if symptoms have disappeared, the patient is allowed to resume full weight bearing. Competitive sports are discouraged until the lesion is completely healed on the radiographs, a process that can take 4 to 12 months.

Surgery is recommended if the lesion becomes detached or unstable, if the pain worsens in a compliant patient, if the patient is approaching epiphyseal closure, or if imaging studies do not improve. Surgery is also recommended in all symptomatic adults with OCD even if they have stable lesions because the risk of fragment degeneration and loose body formation is high.

Surgical Techniques

Arthroscopic treatment allows the surgeon to evaluate the entire articular surface with minimal morbidity, which can be useful when planning for future cartilage restoration procedures. Arthroscopic surgery is ideal for stage I, II, or III lesions. Contraindications for arthroscopic surgery include the inability to fully visualize the detached fragment and the inability to obtain a perfect reduction. Our preferred treatment for stage II or III lesions includes fixation by bioabsorbable implants, cannulated screws, or headless screws. Treatment of macerated unsalvageable lesions in the weight-bearing zones of the condyle includes cartilage restoration procedures.

Figure 7-1 Radiographic stage II osteochondritis dissecans.

Figure 7-2 Radiographic stage III osteochondritis.

Figure 7-3 Radiologic stage IV OCD lesion.

When performing a stabilization of an OCD lesion, our preference is to drop the foot of the bed. Bony prominences and neurovascular structures are well padded. The back of the operating room table is “reflexed” to relax the lumbar spine.

The tourniquet and arthroscopic leg holder is placed low on the thigh, as this provides a better fulcrum for opening up the medial or lateral compartment during the surgery. To allow easy entrance and removal of various fixation devices, some of the retropatellar fat pad and synovium may require debridement. This debridement invariably leads to bleeding and compromises visualization. To avoid this, once the decision has been made to fix the lesion, the tourniquet is inflated.

The arthroscopy begins as any other, with the surgeon performing a diagnostic arthroscopy following his or her own reproducible routine that allows for a detailed inspection of all three compartments. Our method starts with the arthroscope in the suprapatellar pouch looking for loose bodies. The camera is turned to inspect the medial and lateral facets of the patella, and the articulation of the patella and trochlea is evaluated. The arthroscope is then brought down the lateral gutter, and the integrity of the popliteus tendon is checked as well as the popliteus hiatus to observe for loose bodies. The arthroscope is then brought back up into the suprapatellar pouch. The medial plica is inspected for any wear on the medial femoral condyle. The arthroscope is then brought down the medial gutter into the medial compartment. The medial meniscus is probed, and the articular cartilage of the femoral and tibial plateaus is inspected. The cruciate ligaments are inspected next, and the lateral compartment is inspected in a manner similar to the medial compartment.

When the OCD lesion is identified, it is thoroughly inspected. Lesions that are stable, have not displaced, and still have an intact shell of articular cartilage can be fixed in situ. Lesions that are unstable need to be reduced and fixed if possible.

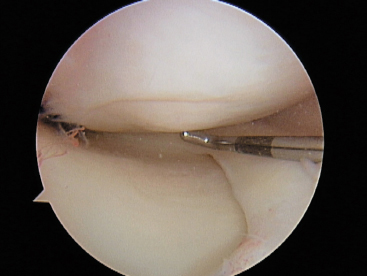

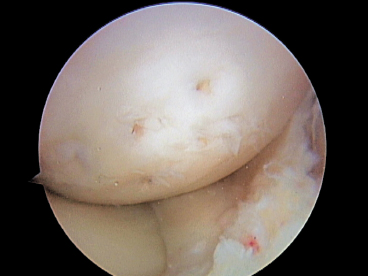

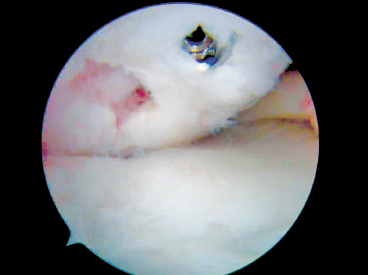

For fixation in situ, our preferred method includes using bioabsorbable fixation (Fig. 7-4). Previously we have used cannulated screws (Figs. 7-5 to 7-7). We have been disappointed in the damage to the underlying tibial plateau from the screw heads despite keeping the patients non-weight bearing.

Once the lesion has been identified and in situ fixation chosen, a spinal needle is used to localize the perpendicular approach to the center of the lesion. A small puncture is made in the skin just large enough to allow the introduction of a soft tissue guide. A drill followed by the fixation device is used through the soft tissue guide. These devices come headed or without heads. The headed fixation devices rely on compression of the OCD fragment by lag fashion similar to standard AO techniques with partially threaded cancellous screws. The headless devices (Arthrex Chondral Dart, Arthrex, Inc., Naples, FL) offers fixation based on a reversal of barbs on the implant. I prefer the headless devices because occasionally the heads can fragment and become symptomatic loose bodies in the knee. The headless devices also seem to minimize iatrogenic chondral damage during insertion.

Figure 7-4 Stable symptomatic OCD fixed with bioabsorbable chondral fixation device.

Unstable lesions must be carefully inspected for the amount and quality of bone that remains on the OCD fragment. If no bone remains on the lesion, the lesion is unlikely to heal. In these cases it is prudent to remove the shell of cartilage and perform a mesenchymal cell stimulating technique or possibly a biopsy for autologous chondrocyte implantation if indicated. If bone is present on the OCD fragment, curetting or microfracturing the base until it bleeds is important to maximize bone healing. Bone grafting the defect has been reported to be beneficial but is rarely required.

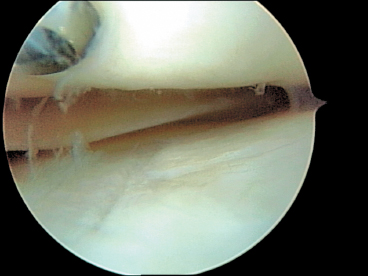

Figure 7-5 Unstable OCD fixed with headed cancellous screw.

Figure 7-6 Articular cartilage damage of tibial plateau due to head of cancellous screw in the femoral condyle.

When the defect is detached and floating in the knee, the risk of mismatch is significant. The OCD fragment continues to grow, receiving nutrients from the synovial fluid. When the fragment does not fit in the crater, a formal arthrotomy may be required to contour the fragment until it can be fixed anatomically. Again, fixation is performed with bioabsorbable fixation that does not need a second surgery to remove.

Postoperatively, patients are kept on crutches for 6 to 12 weeks. A continuous passive motion machine is used for 6 weeks to facilitate healing of the osteochondral fragment. Return to sports activity is prohibited until the patient is asymptomatic, has no effusions, and has radiographic evidence of healing. The radiographic evidence of healing often lags behind the clinical picture and can take close to 1 year before becoming apparent. The downside of returning to sports too early and displacing an osteochondral fragment can be significant, with the patient requiring future surgery and the risk for the development of early degenerative joint disease.

Figure 7-7 Bleeding from OCD screw site at time of cancellous screw removal 6 weeks after implantation. The blood indicates healthy vascularized bone.

Tips and Tricks

It is critical to identify the lesion at the time of surgery. Ninety percent of medial femoral condyle OCD lesions occur in Harding’s area.5 This area is defined on the lateral radiograph by the lines drawn through the posterior cortex of the femur and Blumenstadt’s line. During arthroscopy, flexing the patient’s knee to 90 degrees reveals the majority of lesions that are found on the lateral aspect of the medial femoral condyle.

The first fixation device should be placed in the middle of the lesion to prevent toggling or displacement of the lesion that can occur with an eccentrically placed fixation device.

Sclerotic craters need to be curetted to a bleeding base. If the resulting crater is too concave, a cancellous bone graft can be harvested from metaphyseal bone from the tibia and used to fill in the defect. The OCD fragment should be left 1 to 2 mm proud to allow for subsidence after bone grafting.

Cannulated screws have been favored because of their relative ease of use. They need to be removed at a second surgery because the head of the screw may gouge the articular surface of the tibia (Fig. 7-6). Newer headless metallic cannulated screws are alternative options, but the fibrous cap that forms over the screw’s head often makes removal difficult.

Conclusion

Osteochondritis dissecans is a common problem that can have devastating consequences if not treated successfully. The loss of articular cartilage predisposes the knee to early and rapid degenerative joint disease. New techniques have allowed reproducible healing of these lesions. Bioabsorbable fixation offers good results and eliminates the need for a second surgery to remove cannulated screws.

References

1 Wilson JN. A diagnostic sign in osteochondritis dissecans of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1967;49:477–480

2 Berndt AL, Harty M. Transcondylar fractures (osteochondritis dissecans) of the talus. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1959;41:988–1020

3 Cahill BR, Phillips MR, Navarro R. The results of conservative management of juvenile osteochondritis dissecans using joint scintigraphy: a prospective study. Am J Sports Med 1989;17:601–606

4 Hughston JC, Hergenroeder PT, Courtenay BG. Osteochondritis dissecans of the femoral condyles. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1984;66:1340–1348

5 Harding WG, III. Diagnosis of osteochondritis dissecans of the femoral condyles: the value of the lateral x-ray view. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1977;123:25–26

< div class='tao-gold-member'>