67

Osteoarthritis: Proximal Interphalangeal Joint (Silastic Implants)

Thomas Bienz and A. Lee Osterman

History and Clinical Presentation

This 66-year-old right hand dominant woman had a long history of osteoarthritis involving multiple joints of the hand, and knees. She initially presented in 1989 at age 51 with atraumatic, spontaneous onset of painless distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint arthritis and painful degeneration in the dominant hand’s basal joint requiring ligament reconstruction and tendon interposition (LRTI) arthroplasty. This was followed by similar basal joint symptoms in the nondominant hand requiring arthroplasty 2 years later. Over the next 6 years, she developed progressive degeneration of the left knee as well as the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) and DIP joints of both hands. The left knee required arthroplasty in 1996, but activity modification and the use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) allowed her to avoid further hand surgery until 1999.

At that time, the right long finger PIP joint degeneration compounded by stenosing flexor tenosynovitis of the index and long fingers became sufficiently painful to warrant surgical intervention. The past medical history was additionally significant for hypertension, mild depression, bilateral carpal tunnel syndrome responsive to conservative management and prior cholecystectomy. Medications included Verelan, Lozol, Voltaren, and Prozac.

PEARLS

- Grommets are not indicated for use with Silastic implants in the PIP joints.

- Using the volar approach to the PIP (when indicated) minimizes the risk of damage to the central slip insertion and can be performed simultaneously with a tenolysis to break up adhesions between the FDP and FDS as is commonly seen in long-standing arthritic fingers.

- The implant stems should slide freely in the medullary canal without buckling. If the appropriate size necessary has a stem length that prevents this, the stem should be shortened up to 5 mm to prevent such buckling.

- The largest size implant that fits the space is generally preferred. Implants smaller than size 1 may allow bony overgrowth to bridge and ankylose the joint.

PITFALLS

- In a severely degenerated phalanx, locating the intramedullary canal can be quite challenging.

- Even the blunt leader-tip bur can perforate the cortex, and such perforation will result in a malaligned implant, compromising results. Biplanar fluoroscopy should be used during burring if the surgeon is not absolutely certain of the bur’s path within the phalanx.

Physical Examination

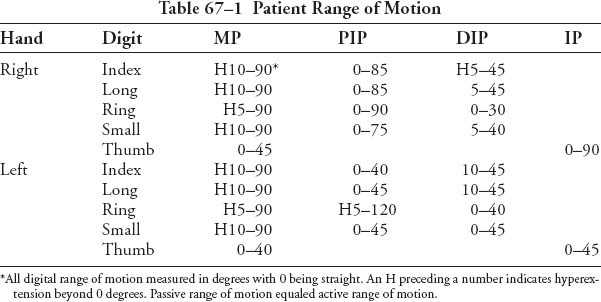

The patient had significant degeneration of the PIP joints with osteophyte formation (Bouchard’s nodes), and similar findings in the DIP joints (Heberden’s nodes). Range of motion (ROM) was most limited in the DIP joints; however these joints did not cause her a great deal of pain (Table 67–1). The right long finger’s PIP joint had a painful arc of motion from 0 to 85 degrees with crepitation. The metacarpophalangeal (MP) joints had well-maintained and painless arcs of motion. There was no erythema, nail pitting, trophic changes, or significant soft tissue swelling. All fingers were neurovascularly intact. The patient reported occasional “triggering” in the index and long fingers when extending from a fully flexed position.

This was associated with pain along the palmar base of the digits and tenderness with a palpable nodule in the flexor tendons at the first annular (A1) pulley.

Diagnostic Studies

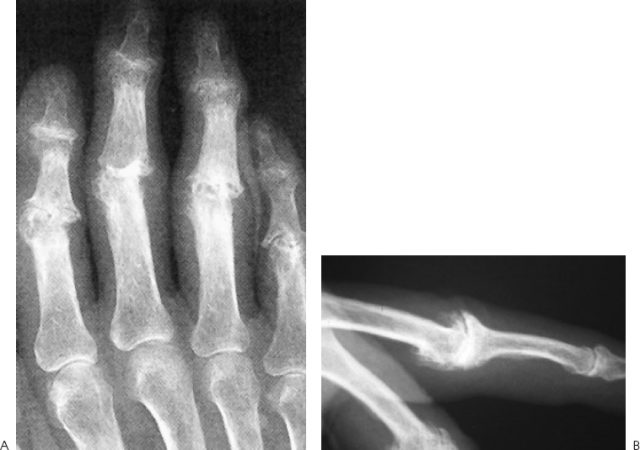

The radiographs demonstrated PIP and DIP loss of joint space, subchondral sclerosis, cyst formation, and osteophytic joint surface widening in both the sagittal and coronal planes (Fig. 67–1). There was a 15-degree ulnar deviation of the index DIP, as well as the long and ring finger PIP joints. The ring finger DIP joint had a 15-degree radial deviation. The MP joints showed a mildly decreased joint space, particularly in the ring and small fingers, and only minimal osteophyte formation. There was evidence of the prior trapeziectomy and LRTI with well-preserved suspension of the first metacarpal maintaining the scaphometacarpal interval. The radiocarpal and distal radioulnar joints were well maintained. There was no significant osteopenia or periarticular erosions.

Figure 67–1. (A,B) Radiographs showing loss of joint space, sclerosis, cyst formation, and osteophytic joint surface widening in the sagittal plane and the coronal plane.

Differential Diagnosis

Degenerative osteoarthritis

Posttraumatic osteoarthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis

Crystalline arthropathy

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Psoriatic arthritis

Diagnoses

Degenerative osteoarthritis involving primarily the PIP and DIP joints with pain primarily at the long finger PIP joint.

Stenosing flexor tenosynovitis (trigger finger) in the index and long fingers.

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common type of arthritis and often affects the hands. The most commonly affected joint is the DIP joint followed by the basal joint, PIP, and MP, in descending order of incidence. As with the treatment of larger joints affected by OA, surgical intervention should be postponed as long as possible using adaptive devices, activity modification, and medical therapy (NSAIDs or steroid injection). When the decreased ROM and pain no longer respond adequately to conservative management, surgical options should be considered. Before proceeding with arthroplasty, the primary contraindications (prior infection and loss of adequate motors) as well as alternative treatments must be reviewed.

Because the index finger is more often used as a “post” against which the thumb pinches than for grasping, index PIP joint stability is more critical than absolute motion. If OA progresses to the point of debilitating pain and/or deformity at this joint, we prefer PIP joint arthrodesis, as an arthroplasty has difficulty resisting the lateral shear of pinch and is likely to collapse into ulnar deviation over time. In contradistinction, the more ulnar digits are used primarily in grasping, and ROM is of paramount importance. In the PIP joints of the ring and small fingers, OA is best treated by procedures that maintain ROM, such as Silastic arthroplasty.

The functional demands of the patient determine the course of treatment for the long finger. In high-demand patients, the long finger PIP joint should be fused for the same reasons listed previously for the index finger. In the low-demand patient who would benefit more from ROM than rigid stability, arthroplasty is the better option. In this patient, the index PIP joint was well maintained, and although all her DIP joints and the three other PIP joints were significantly degenerated, she had pain only in the long finger PIP joint. In the event that other joints had been symptomatic, the DIP joints could have been fused or additional PIP arthroplasties performed.

Surgical Management

Following the induction of general anesthesia and prophylactic administration of 1 g of IV cefazolin, a well-padded tourniquet was applied to the right upper arm. The arm and hand were then prepped with a Betadine scrub solution followed by Betadine paint. An impervious stockinet followed by an extremity drape was then placed. An exam under general anesthesia was undertaken confirming decreased passive ROM in the PIP joint with crepitus and firm end points. An Esmarch bandage was used to exsanguinate the limb, after which the tourniquet was inflated to 250 mm Hg; 3.5x loupe magnification was used for all dissection.

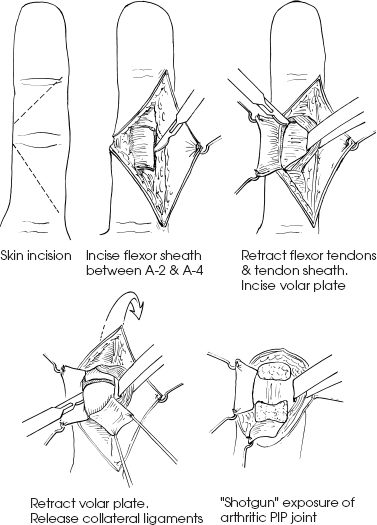

After standard release of the index and long finger A1 pulley with tenosynovectomy, attention was directed to the PIP joint Silastic arthroplasty. A radially based volar V-shaped flap was created with its apex along the midaxial line at the long finger’s PIP flexion crease (Fig. 67–2). This flap was bluntly elevated off the underlying flexor sheath. Care was taken to avoid damage to the neurovascular bundles; crossing vessels were coagulated with bipolar cautery. A transverse flexor sheath incision was made at the distal end of the second annular (A2) pulley. A similar incision was made at the proximal edge of the A4 pulley. These transverse incisions were then converted to an ulnar-based rectangular flap by incising the radial border of the A3 pulley and sheath. The flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS) and flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) tendons were retracted radially through this window in their sheath, exposing the volar plate. The volar plate was incised along its radial, ulnar, and distal borders, freeing it from the middle phalanx (P2) and reflecting it proximally. The collateral ligaments were recessed by inserting a No. 15 scalpel blade between the ligament and articular surface. The blade was then worked proximally to release the ligament’s origin of the head of the proximal phalanx. This allowed hyperextension of the PIP joint to 180 degrees (“shotgun” exposure of the PIP joint) such that the dorsal aspect of P2 was lying against the dorsal aspect of the proximal phalanx (P1).