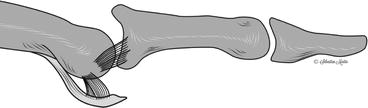

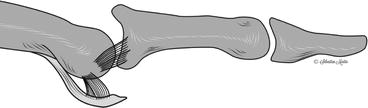

Fig. 13.1

Brett Backwell (Glenelg Australian football club), after amputation of his fourth finger

The professionalisation of some sports and their medical environments have not necessarily led to an optimisation in the treatment of hand injuries. Indeed, even if diagnosis methods have improved, new constraints appeared in terms of sports and economics, to the possible detriment of the athletes’ health.

Nevertheless, the awareness of these facts among the medical staff of sports teams and the hand surgeons specialising in sports pathology has improved the management of top athletes’ hand injuries. This improvement, according to our experience in the treatment of professional teams, is based on an inevitable triple strategy:

A specific approach to these injuries by an elective epidemiology of hand traumas in the context of the sport.

A specialised training in sports medicine, focusing both on the complex hand anatomy and its sometimes sports-specific injuries.

An immediate reactivity of the medico–surgical staff, not only for the diagnosis (which often requires a range of specialised and available techniques), but more importantly for the treatment, because the athlete’s recovery is often important to the season calendar, especially in minimising the athlete’s functional consequences. The role of the media should also be considered in this context and should be better controlled.

13.1.1.1 Specific Epidemiological Approach of Hand Traumas Among Top Athletes

Historically, only lesions of the lower limbs have become subject of specific epidemiological studies. However, today, sports federations and major sports competitions provide more accurate data on the localisation, type, context and severity of the injuries [1].

Indeed, during recent Olympic Games, more than 8,000 injuries were recorded among 35 sports, both in the preparatory and competition phases. The fingers were involved in almost 9 % of these cases. Some sports proved to be more “traumatic” for the hand, such as boxing, handball, volleyball, judo and wrestling, with distributions depending on whether the injuries consisted of fractures, dislocations or sprains.

The statistics provided by sports federations and leagues inform us that ball sports can lead to many injuries, especially rugby, basketball and handball, both in recreational practice and in professional competitions.

The centres specialising in hand surgery have also refined their epidemiological data. They revealed that sports are responsible for 15 % of all hand traumas. In France, for example, approximately 382,000 sport-related accidents are reported, and 40 % of these involve the upper limbs. Regarding only digital lesions, a classification according to severity could be established:

Minor lesions (diaphyseal fractures of the phalanges, interphalangeal sprains, mallet fingers).

Moderate lesions (post-traumatic boutonnière deformities, metacarpophalangeal sprains and dislocations, interphalangeal dislocations, fracture of the pulleys or sagittal bands, jersey finger).

Major lesions (interphalangeal dislocations and fractures, ring fingers).

The club’s physician should be well aware of the importance of these epidemiological data, as he is the one most frequently recording the data. All tools should be available to him in order to facilitate his work and to improve the flow and transmission of information. Thus, online data entry of this information is critical, and federations and sports clubs should allow for the immediate, secure processing of this data.

13.1.1.2 Specialised Training of Sports Physicians in Hand Pathology

Hand surgery is considered a specialty in its own right in many countries and includes a specific training course. The team from la Pitié Salpétrière in Paris (Jacques Rodineau, Gérard Saillant) was among the first to promote the teaching of sports traumatology and to involve orthopaedic surgeons of various specialties in what has become the specialty of hand surgery. Internationally, several organisations are particularly relevant, such as the Aspetar team in Doha, led by Gérard Saillant and Hakim Chalabi; the Swiss Olympic, in Switzerland; or the Australian Institute of Sport.

Indeed, the functional anatomy of the hand is complex, and injuries that may seem benign can quickly degradate to a less favourable prognosis if prompt and appropriate treatment is not applicated. The point is not to teach sports physicians in a comprehensive manner about the 17 ligaments of the trapeziometacarpal joint, but to provide specialised yet simple and reproducible reflexes that will allow them to diagnose serious ligament injuries that could quickly become arthrogenous if case of inappropriate treatment [2].

A dislocation of the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint is another example of injury whose management “on the field” can lead to severe consequences, while a standardised approach could minimise the functional consequences. Indeed, most dorsal dislocations require simple orthopaedic treatments because they are benign injuries (Fig. 13.2). On the contrary, palmar dislocations should all be a priori treated surgically because they can cause a rupture of the median extensor tendon or the incarceration of a tendon or ligament in the joint (Fig. 13.3). However, in the heat of the moment, the player is only focused on obtaining a rapid reduction on the field, and a few minutes later, the finger can became coiled, swollen and inexplorable. Thus, we teach field physicians to take photographs of the injuries with their smartphones right before reduction, which will be critical in determining the treatment strategy (Fig. 13.4).

Fig. 13.2

Anatomical lesions commonly found after a dorsal dislocation. These lesions can correctly be healed by a well-conducted orthopaedic therapy (G. Chick © 2012, all rights reserved)

Fig. 13.3

PIP joint volar dislocation. (a) Anatomical lesions. (b) Surgical aspect with incarceration of a lateral band into the joint

Fig. 13.4

Photograph of a dorsal dislocation before reduction, showing the characteristic “gun barrel” deformation

Some injuries are quite characteristic in certain sports. For example, Bennett’s fractures are often caused by the impact of the thumb’s column on a ball or against the ground while falling. These fractures can be misdiagnosed with a cursory examination and quick analysis of standard X-rays, but being aware of the mechanism and studying some CT images could prevent progression to pseudoarthritis, sub-dislocation and serious arthrogenous deterioration with functional consequences. These consequences are dramatic for the patient, although early treatment would minimise the sequelae, especially thanks to current minimally invasive techniques such as arthroscopy [3], which can be used to entirely control the endoscopic reduction (Fig. 13.5) and to manage any associated joint and ligament injuries [4, 5]. Our team obtained optimal anatomical results with the arthroscopic treatment of Bennett’s fractures in top athletes, as well as early return to sport and minimum functional sequelae (in all first 18 cases assessed, data in press). There are many examples in which an understanding of the hand or upper limb-specific lesions, as well as their therapeutic treatment, could prevent serious functional consequences or even repercussions on an athlete’s career.

Fig. 13.5

Our preferred method for reduction and fixation of Bennett’s fractures: horizontal arthroscopy after intermetacarpal pinning

13.1.1.3 A Competent and Reactive Medico-Surgical Team

A field physician should be able to rely on competent professionals in both hand surgery and sports pathology. Sometimes, this expertise can be useful on the field in order to reduce a rare or resistant dislocation (Fig. 13.6), but in most of the cases, it is after the game, training session or sports competition that it will be important to benefit from a specialised range of techniques with the latest means of osteoarticular examination and the opinion of the hand surgeon.

Fig. 13.6

Reduction on the field of an “irregular” finger dislocation by the surgeon on site

The hand surgeon should be able to quickly make an accurate diagnosis and offer the athlete the best possible treatment. Furthermore, he should also provide information to the medical and technical staff due to his knowledge on sports constraints, accurate and required periods of immobilisation and rehabilitation so as on the particular time frame the athlete can effectively return into action. This double competence can only be achieved through daily contact with athletes, sports physicians and technical staff.

The medico-surgical team should also be able to deal with the many and sometimes controversial questions posed by the increasingly pressing media regarding elite sports. A standardised approach is once more critical, ideally orchestrated by a single player, who should be careful to always protect the confidentiality of the medical data, as it can only be partially shared in accordance to the express consent of the athlete concerned.

In conclusion, sports hand pathology is vast and sometimes quite complex, but an optimal collaboration between the sports physician and the hand surgeon focused on a wide range of available techniques can guarantee a thorough treatment of athletes’ hand injuries. Only a coordinated, standardised approach can help limit the functional sequelae of these injuries in young patients, whether occasional or professional athletes.

Key Points

Hand anatomy in sports gestures

Specific training of sports and field traumatologists by experts

Specifically dedicated medico-surgical team

Suggested Readings

Leclercq C, Gilbert A (1996) Lésions de la Main chez le Sportif. Ed Frison-Roche, Paris

This book covers the main hand injuries encountered in sports. Different experts report on the management, most often surgical, of these injuries, in the field of excellence that is sports pathology.

Fontès D (1992) The value of early ligament repair in severe sprains of the trapezoid-metacarpal joint. Acta Orthop Belgica 58:48–59

Anatomical description of the ligaments of the trapeziometacarpal joint and information on the surgical therapeutic management of these lesions.

Badia A (2007) Arthroscopy of the trapeziometacarpal and metacarpophalangeal joints. J Hand Surg [Am] 32:707–724

Technical description of trapeziometacarpal arthroscopy and results in light of recent indications, including arthropathy and sequelae from traumas.

13.2 Who Decides and Guides the Athlete?

Abstract

Professional athletes are driven by their competitive nature, the desire of fame and glory. Athletes show their superior athletic capabilities from a very young age and only decide at a later age to become professional. The smart ones understand that they are part of a business and prepare accordingly. There are phases in the career of an athlete. The professional athlete enters the professional realm after the Fun Phase between 6 and 12 years of age. The Competitive Phase, usually 12–17 years, is when the professional scouting becomes apparent and injuries are taken more seriously. The Elite Phase is when athletes are scouted for big clubs or national teams. This is first experience with organised medical staff. The smart players pay attention. Ultimately it is the athlete who makes decisions pertaining to medical interventions. This is when the athlete relies on his friends, family and medical staff to guide them through the process. The Guide is that person who the athlete trusts and will be there during and after the intervention.

Professional athletes are driven by their competitive nature. To understand the complex world of an athlete, one has to realise that sport is part and parcel of the entertainment industry. This is big business. The athlete is a potential actor in the big scheme and screen of things. Media (TV, magazines, etc.) rights, marketing and sponsorship deals (Nike, Adidas, Puma to Calvin Klein after-shave) and ticket sales are but a few ingredients in this multibillion industry. Money becomes the key guiding light to many decisions the athlete makes. The athlete evolves into becoming an “entertainer” and will operate like a business. Like all businesses, decisions have to be made; who makes them, in particular, if they are injured and unable to perform? What is the process for treating the injury?

13.2.1 The Athlete Versus the Entertainer

From a very young age, children show their athletic capabilities and are frequently encouraged by their family to pursue a sports activity. Depending on the family environment, some children evolve to become professional sport entertainers or personalities. Some athletes use their talent as a stepping stone to obtain an education and a career in something else other than sports entertainment. These persons remain athletes as they practise sport for pleasure. Those who realise that they will make good and what they believe is easy money decide to become professional athletes.

There are several phases from childhood to adulthood, in which the athlete is subject to injury. It is fair to say that family is the guide and the decision maker until the teen years. During the teen years, the athlete typically heeds the advice of the medical staff linked to the sports programme to which he or she is affiliated. It is different if you are a tennis player or a basketball player.

13.2.1.1 The Phases

The “Fun Phase” is the period by playing many sports until they reach their teens. So from 6 to 12 years of age, most children practise sports in the school environment or with school friends after school. There are those exceptional children who have a talent and whose parents put them on a professional track, sometimes before the age of 8. In this initial phase when children are discovering sports, it is their family that is the guide and who decides how it happens. In this learning process, the roles of the decision makers (parents) and the guide (parents and coaches) evolve.

As athletes get older and become focused on one sport, they go into the “Competitive Phase”. Many athletes do not necessarily know if they want to work as a professional athlete, football or basketball player, for example, until they realise that they can get a lot of attention and favours as well as make a lot of money. Some young athletes have no other option and choose the path of pursuing professional sports as a career. In this “Competitive Phase”, 12 to typically 17 years of age, a natural selection process occurs. Also the risk of more serious injuries becomes apparent. Whilst parents were guiding and deciding for their children in regard to healthcare, at the competitive level things change. The coaches decide which players are the best, and these are the ones who are starters. Those with lesser talent have the opportunity to prove their worthiness, but seldom make it to the elite level; rather they stay at the amateur level.

The “Elite” Phase commences when the athlete is called up to compete by his or her national federation for junior competitions. This is where the problems commence. Parents can no longer keep up and are faced with having to give up permanent jobs in order to guide their children. Parents who do not have the coaching expertise are quickly replaced by coaches who become the guide for the athlete. The parent remains a guide but on a case-by-case basis. Sports agents then appear trying to sign athletes to representation contracts. The successful agent becomes the guide in terms of a professional career.

In essence, the families are the first guides, followed by the coaches and then by the agent.

13.2.2 The Decision Maker

Who decides on what? Ultimately the athlete makes the final decision. The athlete is the one that decides to practise or not to practise (Carlos Tevez). The athlete is the person that performs and decides on which piece of advice they listen to. When it comes to choosing a professional contract, signing with an agent, initially the family may influence the decision, but as years go on, we see athletes changing agents quite a bit, simply out of lack of understanding the mode of communication.

The same can be said about medical treatment. Most athletes do not like to have surgery, and if it can be avoided, they certainly would try. Team doctors are under pressure to get athletes back on the field to play, irrespective of the long-term consequences to the athlete. Athletes are more aware of their bodies and what surgery encompasses. Thus, they do ask for second opinions from specialists, friends and family. Those they trust will give an objective opinion. Based on the information obtained, the athlete alone decides. In the case of a serious injury, the athlete has little choice when rushed to the hospital in an emergency for a broken bone, or worse. They player will seek the advice of those who have and still guide him or her. The final decision on where to play and health issues are the players’ final say.

A distinction is to be made between team sports (e.g. basketball, football, volleyball) and individual sports (e.g. tennis, golf) The approach is different as the personalities of an athlete vary quite a bit when it comes to team versus individual sports. Individual sports athletes are less dependent on the medical staff of a team structure, whereas the team athlete has to first consult with the team medical staff, on a professional level, as it is part of the playing contract.

13.2.3 The Guide

Frequently, this person is very close to the athlete (often a parent or family member) who first gives the impetus to the child to actively participate in sports. They arrange for the child to participate in sports and teach them basic skills, discipline and organisation. There is a bit of psychology involved as is the case between most parents and their children. The guide is either a family member or a member of the coaching/medical staff.

13.2.4 Injury

Every athlete fears an injury. The thought of not being able to practise or being able to play due to an injury is not the first thing on the mind of most players. Where and how does this all start? It varies from one person to another and is dependent on the environment in which the athlete grows up.

It starts mostly with the athlete’s family, a parent, brother, sister or cousin. These are the persons who motivate and push the athlete from a very young age to pursue playing sports. Many times, it is because the family member believes the child has the talent to become a successful professional and reap the glory, fame and money that come with a top flight professional athlete.

Before one goes on, the difference between an amateur and a professional athlete is a fine line. The amateur stops becoming an amateur when the athlete decides he is going to make money from his athletic abilities. The influence of the family changes during the course of the career. In Europe and North America, the process is different. Yet the profile of the persons guiding the player and making decisions is similar.

Athletes are more aware of their body and what surgery encompasses. Thus they do ask for second opinions from specialists, friends, family. Those they trust will give an objective opinion. They player will seek the advice of those who have and still guide him or her. The final decision on where to play and health issues, are players final say. The decision is either good or bad depending on the final result.

13.2.5 Finances

Most athletes are insured when they have a professional contract. It all depends on the sport and the club. Insurance may cost 1–10 % of the value of the contract. It is a complex process, as the athlete should have a medical passport in order to get insurance. The cost of an injury is complicated. A basketball player who is out for a few weeks still gets paid; it is the club that suffers if the player is a key part of the team. The actual cost of operating a finger ranges from USD 5,000 up to USD 20,000; it depends on the complication or simplicity of the intervention.

13.2.6 Comments from Players

Aleks Marić (Australian Olympic basketball team in 2012) pointed out that following his first injury, “The second injury was tough because it was a medical error by the doctors, so to be sidelined for almost 5 months instead 1 month wish it had should have been. I put all my energy to be positive and do well in rehab, and when I did end up coming back onto the court I was mentally exhausted and was unable to help the team”.

Imagine the effect on the player’s career? A family member cannot replace the medical specialist. It is important to have confidence in your medical team.

There is the mental and pragmatic part as well, as pointed out by Vladimir Radmanović (Chicago Bulls NBA team member), “Injuries are the part of this profession and you deal with them as a normal thing. Taking care of your body and injury is very important”.

Players should be able to trust and be surrounded by medical staff as pointed out by Dragan Tarlać (former member of the Yugoslavian and Serbian national basketball team), “I was lucky to have great medical team around me throughout my career, they were great support in every situation”.

As a business, the player should organise the medical support early in his professional career.

A second opinion is as important as the rehabilitation process. Jon Robert Holden (member of the Russian national basketball team) (Fig. 13.7) broke his finger and was given a first opinion, which put him out for a few months. He sought a second opinion and went with that and in a few weeks was back on the court: aged 32 and right handed, JR Holden sustained a spiral oblique fracture of the right small finger in competition (Fig. 13.8). He was appropriately splinted for this closed injury and sent to the National Hand Center in Baltimore. Upon initial examination, the finger was mildly swollen, but showed rather profound malrotation and malangulation.

Fig. 13.8

Oblique proximal phalangeal fracture of the right little finger. (a) Posterior-anterior radiograph. (b) Oblique radiograph

Fig. 13.7

JR Holden playing for Russia in 2008 (With permission of the player). Jonathan Robert Holden is an American Russian professional basketball player (point guard). He won the Euroleague twice with CSKA Moscow (2006 and 2008) and was runner-up in 2007. He was also European Champion with the Russian National Team in 2007

Secondary fracture lines were also appreciated (Fig. 13.9). For these reasons and the juxta-articular location of the fracture, it was deemed best to perform ORIF. All risks and benefits were clearly described and accepted by the patient.

Fig. 13.9

(a) PA Radiograph: Intra-capsular extension (white arrow). (b) Oblique radiograph: This extent of the fracture also demonstrates the foreshortening (black arrows). Malangulation is demonstrated by defined axes

Beside the long, oblique fragment that contained the entire articular surface, secondary fracture lines were stabilised with interfragmentary screws, with anatomical reduction and excellent stability (Fig. 13.10). Clinical rotation and angulation was predictably restored. There were no surgical complications. After rehabilitation, (see Table 13.1), he was able to compete in the following 6–7 weeks.

Fig. 13.10

ORIF. (a) PA radiograph. (b) Lateral radiograph

Table 13.1

Preliminary rehabilitation protocol

5–7 days in operative dressing, then motion |

Wear protective splints when not engaging in rehab |

Sutures out at 10–14 days |

Motion recovery phase to start at 7–10 days |

Out 3–5×/day for 3–5 daysa |

Out 6–8×/day for 3–5 daysa |

Out 10–12×/day for 3–5 daysa |

Strength recovery phase (usually starts when motion >50 %) |

Progress to level of comfort weeks 3–4 |

Sports-specific recovery phase (usually starts when strength >50 %) |

Light ball-handling weeks 4–5b |

Passing and receiving week 5b |

Shooting, rebounding, scrimmage weeks 5–6b |

Return to play target around weeks 6–7 (protected vs. unprotected) |

13.2.7 Conclusion

The athlete is part of a business in entertainment and thus can be replaced. Given the amount of money involved, those who are serious about their professional career organise early on their physical and medical network.

A player does not want to end his career on the wrong medical decision; he wants to play and make money.

Key Points

The families are the first guides, followed by the coaches and then by the agent.

The final decision on where to play and health issues is the players’ final say.

The amateur stops becoming an amateur when the athlete decides he is going to make money from his athletic abilities.

13.3 The Top Level Athlete and the Surgeon