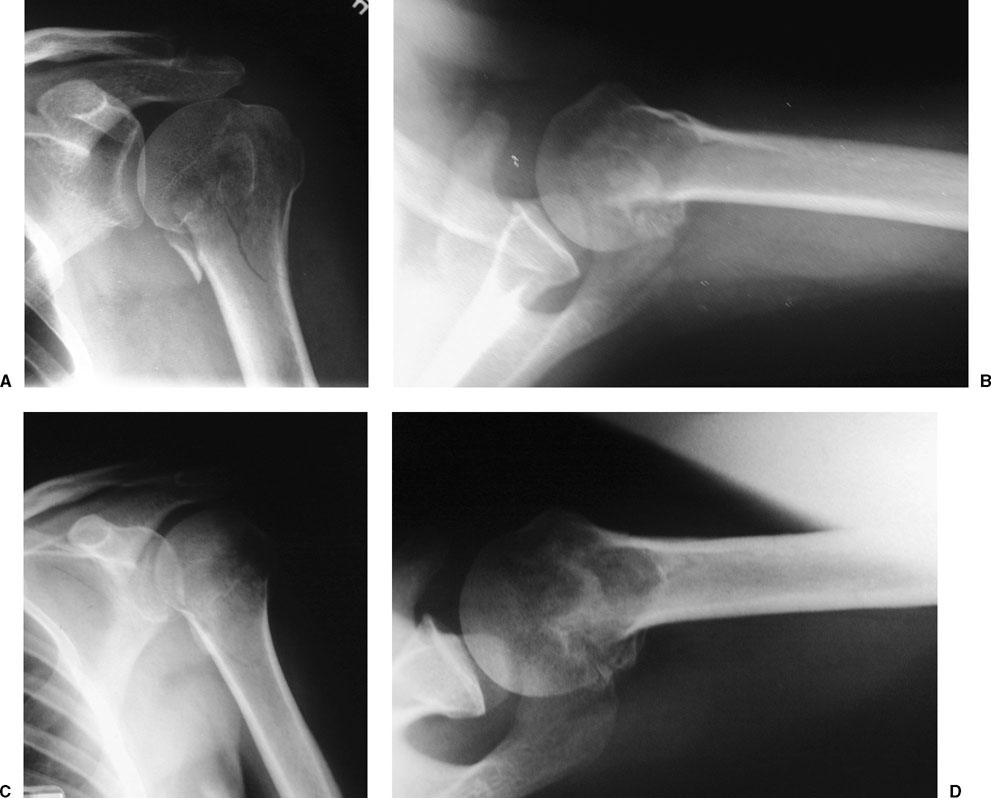

Fractures about the shoulder make up 5% of all fractures.1 Among patients aged 15 to 64, proximal humerus fractures make up almost 2% of all fractures, whereas among those older than 65, proximal humerus fractures make up 4% of all fractures.2,2a Of all proximal humerus fractures, up to 85% are minimally displaced or nondisplaced, whereas 15% are displaced.1,3–13 These minimally displaced or nondisplaced fractures have received little attention in the orthopaedic literature, however. Only a few studies have reported the results of treatment of these fractures.2,3,14,15 A one-part fracture of the proximal humerus, as defined by Neer, is a fracture with less than 1 cm of displacement and less than 45° of angulation between fracture fragments, regardless of the number of fracture lines.9,16 The AO/Association for the Study of Internal Fixation (ASIF) North America classification of proximal humerus fractures is: type A (extraarticular unifocal fracture), type B (extraarticular bifocal fracture), and type C (articular fracture). Each category is then further subdivided to give a complex system that according to its authors “does not apply as uniformly…as it does in diaphyseal fractures.”17,17a Using the AO/ASIF system, minimally displaced fractures can be classified as either type A or B, depending on whether one or multiple fractures lines are present. In a study by Koval et al,18 one-part fractures were most commonly found to be fractures of the surgical neck (42%) and greater tuberosity (30%) (Figs. 4-1 and 4-2). Multiple fracture lines in the proximal humerus accounted for the remainder of minimally displaced fractures (28%) (Fig. 4-3). Proper classification of one-part fractures is important because it will determine the treatment plan. Minimally displaced fractures are primarily treated nonoperatively; however, if more significant displacement is identified (i.e., greater than 1 cm displacement or more significant angulation), the fracture is no longer a one-part fracture, and operative management should be considered. This emphasizes the importance of proper radiographic imaging of the fracture. Fractures of the greater tuberosity (Fig. 4-4) warrant special mention because some authors believe that less than 5 mm of displacement should be accepted.19–21 Santee20 reported that healing of a fracture of the greater tuberosity in slight displacement might result in disability. McLaughlin21 reported that patients who had 5 to 10 mm of displacement of the fragment often had a prolonged convalescence, with some having permanent pain and disability and with 20% needing a reconstructive procedure. Miller,22 however, maintained that incomplete reduction was compatible with a good functional result providing the greater tuberosity was not left in an elevated position under the acromion. Jakob and co-workers6 recommended nonoperative treatment for displacement of 5 to 10 mm because the tuberosity usually remains in an acceptable position. At present, the issue of greater tuberosity fractures with borderline (greater than 5 mm and less than 10 mm) displacement remains uncertain, with both nonoperative and operative treatment recommendations. This type is discussed in Chapter 5. Most one-part fractures result from a fall onto the outstretched upper extremity or onto the shoulder from a standing height. They occur most commonly in elderly, osteoporotic patients, with the prevalence twice as common in women as in men.1,6,8 In younger patients, proximal humerus fractures are usually caused by higher energy trauma, such as a motor vehicle accident. FIGURE 4-1 Trauma series of a one-part surgical neck fracture. The scapular anteroposterior (AP) (A), lateral (B), and axillary (C) views show preservation of the alignment of the proximal humerus. There is a nondisplaced greater tuberosity fracture line. For patients who sustain a proximal humerus fracture, a thorough history should be taken, including the age of the patient, associated medical conditions, work requirements, handedness, recreational activities, and expectations. It should be accompanied by a complete clinical evaluation of the involved shoulder and the ipsilateral upper extremity. In higher energy injuries, the neck and chest should be evaluated. Ipsilateral fractures of the humeral shaft, elbow, forearm, or wrist can occur. The patient with a one-part fracture may have pain, tenderness, and swelling about the shoulder, but to a lesser degree than with more displaced fractures. There will most likely be no appreciable crepitus or deformity about the shoulder. Ecchymosis may be present (Fig. 4-5), but lacerations and open fractures are rare. The patient may also be unable or unwilling to raise the arm. A thorough neurovascular exam must be performed and documented carefully. Because the axillary nerve is the most frequently injured nerve in proximal humerus fractures, an exam of the sensation over the lateral deltoid and motor function of the three parts of the deltoid is required if pain allows. In a prospective follow-up study by Visser et al,23 nerve lesions were identified by electromyogram (EMG) in 59% of nondisplaced fractures, with the axillary and suprascapular nerves being the most commonly affected. The examiner should determine if the proximal humerus moves as one unit or not, to gain assurance that the motion is occurring at the glenohumeral joint and not at the fracture site.18 With one hand supporting the patient’s forearm and elbow and the other placed at the proximal humerus, the examiner carefully rotates the patient’s shoulder and determines if the proximal humerus moves as “one part” (Fig. 4-6). Only if the fracture moves as a unit can the patient proceed with early passive shoulder exercises. Nonunion or malunion may result if early motion is implemented in fractures that are unstable.16 FIGURE 4-2 Scapular AP (A), lateral (B), and axillary (C) views of a one-part greater tuberosity fracture. The fragment is less than 1 cm displaced. The standard trauma series of shoulder radiographs (scapular anteroposterior [AP], scapular lateral, and axillary lateral views) are necessary for the evaluation of any proximal humerus fracture and are the next step in evaluation. Correct classification of the fracture depends on being able to visualize the degree of displacement or angulation of the fracture fragments. The axillary lateral view is useful for determining displacement of the humeral head on the glenoid and posterior displacement of the greater tuberosity fragment. For stable fractures, carefully obtained internal and external rotation views may help visualize the proximal humerus. The external rotation view is useful for seeing the anatomic neck and the greater tuberosity. Computed tomography (CT), although potentially helpful in displaced fractures, is generally not necessary for one-part fractures; however, if the amount of posterior displacement of a greater tuberosity fracture is in question, a CT scan should be obtained. Nonoperative treatment is the primary treatment for one-part proximal humerus fractures. Healing occurs largely due to the substantial soft tissue envelope surrounding the proximal humerus that remains intact.8,16 Satisfactory, good, or excellent results have been reported in 80 to 97% of patients treated nonoperatively for one-part proximal humerus fractures.3,10,14,18

One-Part Fractures

Description

Description

Clinical Evaluation

Clinical Evaluation

Radiographs/Imaging Studies

Treatment

Treatment

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree