Introduction

People are occupational beings. From very early childhood they explore the world around them to discover the ways in which they can learn about, manipulate, utilise and dominate their environment. From first waking up in the morning, getting out of bed, washing and dressing, preparing and eating breakfast, communicating and responding to all surrounding stimuli; these are all occupations. The group of Canadian occupational therapists who developed the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (Law et al., 2005) devised an exercise to direct colleagues and students towards an understanding of the concepts of everyday occupational performance. This exercise suggests that you sit down with a friend, preferably someone who is not a fellow student. Each of you should take a clean piece of paper and, starting in the bottom, left-hand corner, write down the time as it is at the moment. Above that write down each previous half hour until you have covered 24 hours. Next think back and list all the things you have done in the past 24 hours. Once you have made your list, identify those occupations that you consider to have been carried as a result of habit, and those that you have judiciously or spontaneously decided upon. Now make a summary.

- How many of your occupations were directed towards looking after yourself?

- How many were related to your current work?

- Were some of them part of your leisure?

Go through your list and work out how much time you spend on each category of occupation. Would the result be different if the list was made in term time compared with the weekend or holiday?

Compare your list with that of your friend. How similar are your lists and the categories of occupations? Is your interpretation of work and leisure the same as that of your friend? If you were 10 years younger what differences would there be in your average daily occupations? This exercise highlights the importance of our everyday occupational performance, and how each person may have a different interpretation of their everyday occupations. For example, cooking may feel like work for one person, but pleasurable leisure to another. Whereas a mother may enjoy and look forward to bathing her baby, a carer may consider this aspect of the working day as arduous.

Framework for understanding human occupation

At this point it would be helpful to reflect on a framework to organise your thinking, when interacting with individuals who have occupational performance problems in daily life.

The core values and beliefs about human occupation are located within a paradigm of occupation and these ideas are articulated fully within the study of Occupational Science (Clark & Zemke, 1996) which studies the importance of the relationship between occupation and human beings. The occupational role issues (e.g. mother, worker, friend etc.) that people experience and how to intervene can be located in different models of human occupation, for example the Model of Human Occupation (MOHO) (Kielhofner, 2007), the Canadian Model of Occupational Performance-Enablement (CMOP-E) (Townsend & Polatajko, 2007) and the Kawa Model (Iwama, 2006) to name but a few. These and other models of human occupation share similar concepts in relation to the factors that need to be considered for understanding the occupations of an individual, these are broadly:

- occupational roles: identifies the perceived roles held by the individual;

- occupational performance: identifies the particular performances, relating them to self-care, work and productivity, and leisure;

- occupational performance skills: identifies the motor and process skills required to perform the occupations;

- occupational performance skill capacities that underlie the maintenance of performance skills, including sensorimotor, cognitive and pyschosocial aspects;

- environment: identifies how the individual interacts with the temporal, physical (architectural), social and cultural environments, and their spiritual response to their present existence.

Occupational role

A person’s occupational life is closely linked to the roles that they fulfil in everyday living. An individual may play a number of roles in one day, for example acting as a mother, employee, carer and wife at different times of the day. Another example could be the roles of flatmate, friend, student, teammate and lover. Behaviour and occupational lifestyle can be determined by the roles that an individual is called upon to fulfil, and these will also have an effect on occupational performance. When one is highly motivated performance may be enhanced, for example preparing a meal for a much-loved friend. Conversely, a task that is routine or boring may be performed less effectively, for example in the role of homemaker, doing the ironing may be a tedious task.

Occupational performance

Each human occupation has a level of performance that must be achieved in order to be effective. Problems caused by trauma, disease or arrested development affect performance in many different ways. The changes may present in areas of mobility, manipulation, cognitive function or social interaction. Refer back to the summary of your own daily occupations, of which some were self-care, some work and productivity, and others leisure.

- The daily occupations relating to self-care would include dressing, feeding, grooming, toileting, bathing/showering and using transportation.

- Work and productivity would include finding and keeping a job, voluntary/unpaid work, education at school or university, instructive play, cleaning the house, doing the ironing, etc.

- Leisure occupations include visiting and socialising, reading, sport, travel, hobbies and crafts whether individually or in a group.

A therapist, in conversation with a client, will be able to elicit the client’s interpretation of daily occupations, a process that may assist in the understanding of the particular client’s motivation and attitude towards aspects of the problems in everyday life.

Occupational performance skills

The level of skill required to perform occupations is different between tasks. A computer operator must achieve a high level of manipulative skill in operating the keyboard and the mouse. As well as manipulation, other important skills in the operation of a computer would be:

- motor skills, including positioning, stability and alignment; bending, reaching and gripping;

- process skills, including the ability to choose, enquire, continue, organise and terminate.

The assessment of motor and process skills (Fisher, 2010) can take place during performance of the client’s chosen occupation of daily living, giving the therapist essential information on the impact that the client’s condition has had upon their everyday life.

Occupational performance skill capacities

Occupations depend on the basic processing and integration of all the information entering the nervous system from the world around us, which then activates the correct motor performance. Sensorimotor processing is also the basis for cognitive processing which allows people to make decisions, to modify performance, and to recall past experience of successful outcomes. These capacities are:

- sensory awareness, sensory processing and perceptual processing;

- higher cortical functions of cognition and strategic planning;

- psychosocial components related to psychological, social and self-management skills, for example, how people express their values and interests, conduct themselves with others in a social gathering and manage their time during the day.

Environment

The environment has an important effect on occupational performance. An older person who can function reasonably well in their own home may be unable to be independent if he or she has to move to a different environment. The presence of steps, a slippery floor or a gravel path can all interfere with safe and confident walking. A soft chair, a low bed and the absence of adequate heating can impede successful independent living. Adaptation of the environment may be a major factor in assisting an individual to learn to perform effectively. The components of the environment to be considered are as follows:

- Temporal factors, including the context of the client’s past, present and possibilities for the future, may influence the time it takes to complete an occupation and the capacity of the client to sustain effort for the period involved.

- The physical architectural environment, that is the layout of the area and objects within it. This may vary in different situations, which may alter the patterns and strategies needed to perform an occupation.

- The social environment can have a marked effect on performance, for example being watched and assessed increases performance stress and may interfere with normal sequencing.

- The cultural environment plays a significant role in performance, influencing the way that an occupation may be carried out and the tools and equipment used.

An individual’s spiritual response to each of the performance components may have an effect on the sense of the meaning and purpose of occupations. For example, feelings of self-esteem and personal dignity, responsibility and personal courage, and other personal spiritual beliefs may be important.

Case scenarios

Chapter 13 analysed the core positions and movement patterns of an individual that underpin occupational performance skills..

Here, performance skills are extended into occupation, identifying the many interactive factors that may have an influence. These include: the role of the individual within a family and work context, personal motivation, and the motor and process skills required for particular tasks. These are the factors that a therapist can assess and learn to assemble to assist an individual to learn to improve performance, or to take advantage of assistive devices and adaptive methods of performance in their daily lives.

Case scenario exercises

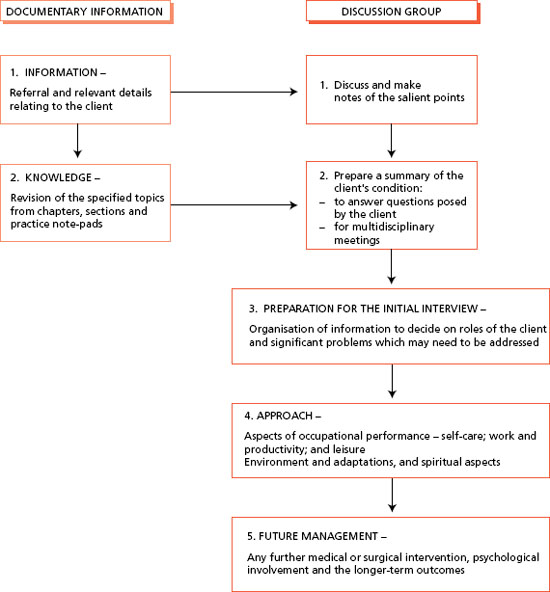

Six case scenario exercises have been devised to encourage the reader to use this book as a source of reference and to apply thought to the way in which a therapist might direct intervention and advice to assist a client. It is suggested that you form a small group with your colleagues and discuss and think through each case scenario and, using the framework given below, put together ideas related to working with each client.

Format for discussion

By working in a group, you will have the opportunity to discuss each case scenario and share ideas. Each exercise will provide the referral information from which the important facts can be ascertained. The relevant normal structure and function of the systems involved should be revised from chapters in the book, together with information given in the practice note-pads. A summary of the background information should be prepared in case the client wants more knowledge of the condition and to equip the therapist for in-depth discussion with other members of the multidisciplinary team. Each client will have a personal approach to the problems that may arise as a result of disease, injury or developmental delay, and the members of the discussion group may have a number of differing ideas. A summary of what actually occurred in each case scenario is presented in Part II. It will be interesting for you to compare your thoughts with this summary, it must be remembered that in the ‘real world’ the client would respond to the therapist during conversation. The conclusions in the summary may be different from those reached by the group. However, the important part of this exercise is the process of working through the case and preparing adequately for early conversations with the client.

Comment

The approaches and conclusions to the case histories that are presented reflect the ideas of the authors and advisors and do not relate to specific theoretical models of occupational therapy. You as the reader are encouraged to consult textbooks and articles that describe and comment on the utility of different models of occupational therapy (see Duncan, 2011). The importance of readers’ participation in these exercises is to ensure that you understand the significance of the biological and biomechanical capacities alongside the psychosocial, intellectual and environmental issues that may influence the healing and/or coping process. The Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (Law et al., 2005) has been used to guide the reader into thinking about the social, domestic and spiritual aspects of clients’ responses to incapacity and the way in which the environment can impinge upon these dimensions of living. The Assessment of Motor and Process Skills (Fisher, 2010) has been cited to alert the reader to the complex interplay of factors that determine the way in which occupational performance skills are carried out. We trust you will find these exercises helpful and that they help you to consider the broader influences on clients’ health and everyday occupations.

PART I

Part I begins with an example of a case scenario that has been written to demonstrate how to tackle the other six.

Example case scenario

Information

Kathleen is a 64-year-old librarian in full-time employment with the District Council Library Service. Recently, she has been feeling discomfort and aching in the area of the groin and the front of her thighs, which becomes more acute as she climbs stairs. She discussed this with her husband, a retired businessman, who said it was probably due to her age. Her daughter, a pharmacist at the local hospital, thought otherwise and suggested that Kathleen talk to the family doctor. The doctor thought that Kathleen may have osteoarthritis and he arranged for her to have an X-ray at the local hospital. The letter from the radiologist confirmed his suspicions, saying that Kathleen has osteoarithitic changes in both hip joints and some possible changes in the sacroiliac joints. Kathleen expressed distress at this diagnosis as she had planned her retirement, in 18 months time, to include active grandparenting, working to renovate her garden and planning visits to the National Trust houses and gardens. Because he realised her potential problems her doctor referred her to the community occupational therapist for advice and help.

Therapist’s knowledge

Osteoarthritis is a process of degeneration due to the wear and tear on specific joints of the body. (Refer to the hip joint in Chapter 8 and Practice note-pad 1B.) The hip joint is the joint that transfers the weight of the trunk, head and upper limbs to the floor by means of the lower limbs. (Refer to Chapter 13, standing and walking.) Those people who stand for most of their working lives are therefore more prone to this problem, for example teachers, shop assistants, waitresses and librarians. The syndrome is characterised by inflammatory incidents around and within the joints, and particularly within the bursae surrounding the joints. Pain is felt in areas not related to the joint location and is often at its worst in the early hours of the morning and particularly following a busy day. Kathleen’s interests are noted by the therapist and she expects to mention these quite early in her discussion with Kathleen.

Therapist’s preparation for an initial interview

Looking at the referral, the occupational therapist was able to ascertain that Kathleen was married, and from the address realised that she probably lived in a 1930s semidetached house in the suburban part of the town, quite close to shops but a long way from the town centre. As a married woman Kathleen would fulfil the roles of wife, mother, grandmother (according to the referral), gardener, organiser and a member of a work team. She had worked throughout her life and was someone who was familiar with books and resource information. She would know how to cooperate within a team of employees, for example sharing the workload, working conditions, holiday requests and problems relating to sickness leave.

Therapist’s approach

The therapist makes an appointment to talk with Kathleen and asks her about her feelings relating to the recent diagnosis. Kathleen expresses anxiety about her condition and how to deal with it, particularly the possible changes in her roles, but wishes to continue working until she reaches retirement age. The therapist asks how much Kathleen knows about osteoarthritis, and offers further information about bursae and their assistance in muscle action around a joint and why they may become inflamed in the course of the disease. The therapist also suggests that Kathleen find a nursing medical book in the reference library to find out for herself about the hip joints and the surrounding muscles. Kathleen has been taking the new anti-inflammatory drugs, prescribed by her doctor, but that she stills wakes up in pain in the early morning.

Self-care

The therapist suggests that she might try taking her medication at night, instead of the morning, and in this way she should gain the maximum benefit throughout the night. A suggestion is that Kathleen keep a working diary for a month so that she develops an awareness of the situations that may increase the discomfort. For example, is her favourite chair suitable for relaxation or should it be higher and firmer, with better back support? Is her bed easy to get in and out of, is it firm enough? What effect do long periods of standing or long periods of sitting have on her levels of discomfort?

Work and leisure

At work there will be tasks that will allow her to sit down for some of the time. Kathleen could discuss her problems with her colleagues and between them they should be able to organise her contribution to the library work, making the most of her capabilities and experience. In what ways could she tackle her gardening work most effectively? The therapist understands that Kathleen will gain a fuller understanding of her own condition than any outsider, and by encouraging Kathleen to monitor her own progress, she may come to recognise factors of cause and effect, and will therefore become more able to cope with the day-to-day management of the disease and any deterioration over time.

Environmental a daptations

Certainly the therapist will be able to offer ideas that have been tried in the past, such as the use of a kneeling stool for gardening (and even for locating all sorts of objects on low shelves throughout the kitchen and house). She may also discuss Kathleen’s driving experience and whether she feels able to continue driving her car. An automatic car may be easier for Kathleen to drive and the therapist might suggest that she takes a test drive to ascertain the advantages or otherwise of making this change. The provision of a high stool to obviate the long standing periods when cooking, washing-up, ironing or working in the greenhouse may be of great assistance, and when she is visiting National Trust properties she should monitor how long she can cope with walking and standing before taking a rest.

Future management

The therapist asks Kathleen about her feelings relating to her future and the changes that will, in time, take place. Will she And the psychological resources to cope with the inevitable restrictions on her life and the possibility of asking others to support her on occasions? Relating to the future, the therapist will be able to give her information concerning total hip replacement and its outcomes, which may be needed if the pain becomes more intense and intolerable.

Further case scenarios

The next six case histories are designed for group discussion (Figure 14.1). The referral information about the case and an indication of the relevant knowledge related to the client’s condition are given. Part II presents what actually occurred, so that the outcome of the discussions can be compared.

Case scenario 1: Mabel; the ageing process

Information

Mabel aged 75, is a widow of some years. She has a caring and supportive family of 10 children, all married and living nearby, who see her regularly, bring in hot meals and helping out with her heavier household tasks such as changing the bedding, vacuum cleaning and cleaning windows. Mabel has some hearing impairment but is otherwise a bright, assertive, independent person. She lives in a four-bedroomed terraced house, but has recently put her name down to be rehoused in a bungalow. She was admitted to hospital with fracture dislocation of both malleoli of the right ankle and torn ligaments of the left ankle. It seems that she thought that she had heard the front doorbell, then it rang again and she jumped up quickly and fell. After 3 weeks’ postoperative hospitalisation she was discharged to her daughter’s home, where a bed was put downstairs for her. At this stage Mabel was partially weight-bearing and using a Zimmer walking frame. At the follow-up clinic 3 weeks later Mabel was referred to the community physiotherapist, and after 2 weeks of physiotherapy treatment Mabel was gaining in confidence and started to work on going up stairs with a view to having a bath. At this time she expressed the wish to return home but her daughter was anxious and doubtful about her ability to manage on her own. The community occupational therapist was asked to carry out an assessment of bathing and kitchen tasks in preparation for her return to her own home.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>