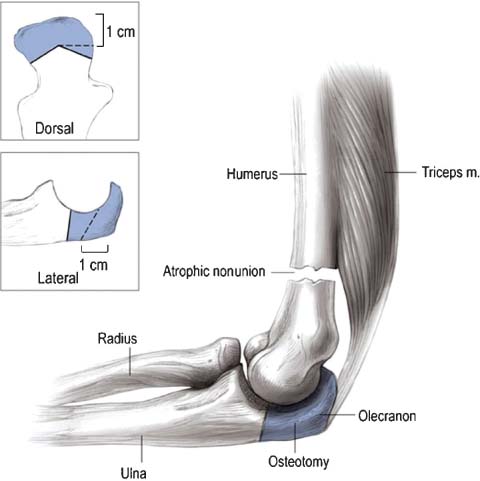

16 Nonunions of the Distal Humerus Good and excellent results can be expected after anatomic reduction and rigid internal fixation of intraarticular fractures of the distal humerus.1–3 In a small subgroup of patients, however, complications such as elbow stiffness and periarticular fibrosis, heterotopic ossification, ulnar neuritis, malunions, and delayed unions or nonunions occur.2 Fortunately, the prevalence of delayed unions and nonunions of the distal humerus is low, ranging between 2 and 10%.1–4 Although a delayed union or nonunion of the distal humerus can be pain-free and treatable with a brace in a small minority of patients, most patients complain of a frail, painful, and essentially nonfunctional upper extremity. The proximity of the ulnar nerve to the periarticular elbow instability often leads to exacerbation of an existing ulnar neuritis compounding to the patient’s disability. Operative intervention of some type is thus often required for these patients. Challenging associated factors that often face the treating surgeon are compromised soft tissues due to previous interventions, poor bone stock, osteopenia, broken hardware, and small fragment size. The delayed union and nonunion can be classified according to Mitsunaga5 and colleagues into supracondylar, transcondylar, T-condylar (or intercondylar), and low transcondylar. The type of nonunion is classified according to Weber and Çech into atrophic, oligotrophic, or hypertrophic.6 The diagnosis of a synovial pseudarthrosis can only be made intraoperatively and is characterized by a fluid-filled sac with a synovial lining. Infection is diagnosed based on clinical examination (drainage, fistula, etc.) and/or by intraoperatively obtained deep cultures prior to administration of antibiotics. Previous operative reports should be scrutinized for details regarding fracture configuration, position of the ulnar nerve, difficulties (if any) encountered, and comments on bone quality. If hardware is already in place, it should be determined which type so that appropriate instruments are available for removal. Preoperative evaluation of the patient’s range of elbow motion, neurovascular status, previous scars, and signs of infection is important. A detailed examination of the ulnar nerve is paramount, including its mobility, position, absence or presence of a Tinel’s sign, and a detailed sensory and motor function. Elbow radiographs in at least two planes will often give sufficient insight into the bony problem (Fig. 16–1). Based on these radiographs, one should be able to classify whether the nonunion is atrophic, oligotrophic, or hypertrophic. The configuration of the nonunion needs to be outlined, especially if it involves the articular surface. Occasionally a computed tomography (CT) scan is needed to identify which portions of the distal humerus are ununited. It can be helpful to evaluate the residual motion at the elbow and/or nonunion site by obtaining two lateral radiographs with the elbow in flexion and extension, respectively. This will often show that most – if not all – motion is at the nonunion site and not at the elbow joint itself. The goal of all these preoperative evaluations is to understand the exact nonunion configuration, allowing the surgeon to make a line drawing of the various fragments, their reduction, and expected final montage. This preoperative exercise prepares the surgeon in a stepwise fashion for the procedure, its potential problems and pitfalls, and provides both the surgeon and patient with realistic expectations of outcome and potential complications. Other than routine preoperative laboratory studies no specific blood tests are needed. In case of (suspected) infection, a complete blood count including differential, an erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein can be determined. Aspiration of the nonunion site to determine evidence of infection can be considered, but is seldom done in our practice. Figure 16–1 (A-C) An 81-year-old man presented 6 months following a right-sided distal humerus fracture with complaints of pain and limited function that was originally treated in a elbow brace. Motion at the nonunion site is obvious radiographically. Only a very small number of patients will not require surgery and might be considered for brace treatment. In our experience the vast majority of patients with a nonunion of the distal humerus will benefit from operative intervention and are able to undergo the proposed treatment. Successful operative treatment is based on an extensile release, removal of failed hardware, adequate débridement, and rigid fixation with liberal use of bone graft allowing early motion. Reconstructive options other than open reduction and internal fixation of distal humerus nonunions are distraction arthroplasty, allograft (cadaveric) replacement, elbow arthrodesis, and total elbow arthroplasty. Better total elbow prosthetic designs as popularized by Morrey and Adams7 have improved upon the initial relatively poor results of total elbow arthroplasty for distal humeral nonunions. Still, their proponents agree that this should only be used as a salvage procedure, i.e., if stable open reduction and internal fixation are not possible or the articular surface or joint anatomy are not salvageable. Limited data on the use of cadaveric allografts are lacking in long-term results and complications such as instability, resorption, and nonunion may occur.8 Lastly, the option of distraction arthroplasty for posttraumatic dysfunction as described by Morrey is a technically demanding salvage procedure associated with a high complication rate.9 The operative procedure begins by positioning the patient on a beanbag in the lateral decubitus position. Alternatively the patient can be placed prone with the upper arm resting on a small armrest keeping the elbow at 90 degree’s flexion. A sterile tourniquet is inflated and the arm is placed across the chest over a blanket roll if in the lateral position. If an iliac crest bone graft is to be taken, this area is draped out simultaneously. Depending on the surgeon’s handedness and preference, the surgeon and first assistant will each be on one side of the arm. Using a sterile marker, all previous incision (s) are marked out. Ideally, old incision (s) are incorporated in a midline posterior approach lowering the risk of ischemic skin necrosis. To facilitate exposure of the ulnar nerve, the procedure is started under tourniquet. The ulnar nerve is best first localized proximally where it emerges beneath the triceps tendon. Any previous surgery around the elbow warrants extra caution, given the possibility of scarring or a change of location of the ulnar nerve. If extensive scarring around the nerve is present, the dissection is more complicated and the surgeon should be prepared for a careful microdissection with the use of surgical loupes. The nerve is followed for at least 7 cm after entering the flexor pronator mass. The first branch of the ulnar nerve (articular branch) is often sacrificed because it tethers the nerve to the joint, preventing adequate release of the nerve. Its next branches should be carefully preserved as they supply the flexor carpi ulnaris. Once the ulnar nerve is dissected free it is tagged with a Penrose drain. Proximally, the distal aspect of the intermuscular septum should be released to increase mobility of the ulnar nerve. If preoperative ulnar neuritis is present, in addition to extensive scarring around the nerve, an external neurolysis should be performed. In case of an intraarticular nonunion, malunion, or a low transcondylar nonunion, the best exposure of the joint is obtained through a chevron intraarticular olecranon osteotomy (Fig. 16–2). However, if the delayed or nonunion is extraarticular (supracondylar), a triceps splitting, triceps preserving/reflecting or dividing approach can be sufficient. A combined medial and lateral approach is, in our experience, insufficient for an intraarticular or low transcondylar nonunion. Only for an isolated medial or lateral condylar delayed union or nonunion can a unilateral approach be considered. In case of a previous olecranon osteotomy that has not yet healed, it is prudent to reutilize this same approach. Figure 16–2 The olecranon osteotomy is angulated (as shown in inset), forming an apex to facilitate reduction and providing additional rotational stability for fixation. (From Helfet DL, Kloen P, Anand N, Rosen HS. ORIF of delayed unions and nonunions of distal humerus fractures. Surgical technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2004;86-A(Suppl 1):18-29. Reprinted by permission.)

Classification

Patient Asssessment

History

Physical Examination

Radiographic Assessment

Laboratory Studies

Treatment

Nonsurgical Treatment

Surgical Treatment

Surgical Reconstructive Procedures

Authors’ Recommended Treatment

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree