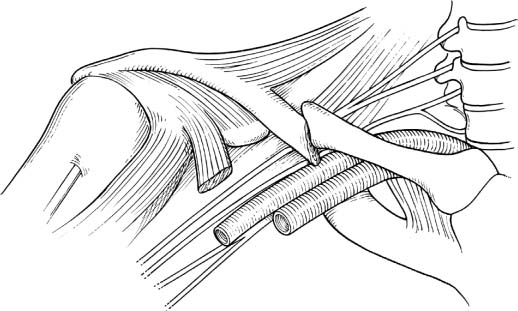

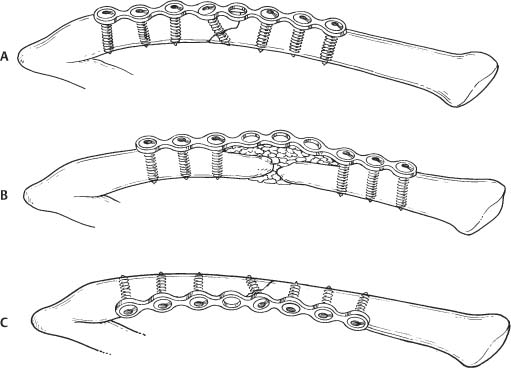

2 Nonunions of the Clavicle Clavicle fractures are common, comprising ~44% of all shoulder injuries and ~3% of all fractures. Most fractures of the clavicle involve the midshaft (69 to 81%). Fortunately, surgery is rarely indicated for these fractures because nonoperative treatment will lead to a good result in the vast majority of patients. Established indications for operative fixation of clavicle fractures include open fractures, pathological fractures, segmental fractures, fractures that compromise neurovascular structures, impending skin penetration by fracture ends, and significant displacement. There is no clear guideline, however, as to what amount of displacement can be accepted. Other reasons to operate on these fractures include (1) the presence of a so-called floating shoulder, or (2) if the procedure would promote early mobilization in a polytrauma patient. Finally, acute operative treatment can be called for in the throwing athlete to allow for earlier recovery and for cosmesis.1–3 A recent systematic review of 2144 midshaft clavicle fractures showed that nonoperative treatment of 1145 fractures resulted in a nonunion rate of 5.9%. When limited to 159 displaced fractures, the nonunion rate of non-operative treatment increased to 15.1%.2 Etiological factors suggested to predispose to a nonunion include open fracture, initial displacement, comminution, refracture, inadequate immobilization, and initial open operative treatment.1 Given these statistics the surgeon will be more likely to operate on a clavicle nonunion than on an acute clavicle fracture. Various tactics have been described for treating these nonunions utilizing either internal (plates and screws or intramedullary devices) and external fixation.2,3 Fractures on either end of the clavicle are much less common, but require surgical intervention relatively more often. Medial clavicle fractures can (partly) obstruct the esophagus and upper airway when the displacement is posterior, and most of these will need reduction and stabilization.4 Although a large Scandinavian study reported good results after nonoperative treatment of lateral clavicle fractures, there is an ongoing debate whether lateral clavicle (intra- and extraarticular) fractures need fixation.5 Although nonunion of the medial and (mostly) lateral clavicle are not uncommon, literature on how to treat these is sparse. Fractures of the clavicle are often classified based on location according to Allman6 into middle third (type I), outer third (II), and medial third (III). The nonunion type of the clavicle is most often classified according to Weber and Çech7 into atrophic, oligotrophic, and hypertrophic. In their classic treatise on nonunions, they describe clavicle nonunions with shortening, those with a defect and shortening, and distal clavicle nonunions. Distal or lateral clavicle fractures and nonunions have also been classified according to Neer on the basis of their relation with the coracoclavicular (CC) ligaments (types I and II) and whether or not the fracture extends into the acromioclavicular (AC) joint (type III).8 Medial clavicle fractures and resulting nonunions are often a growth plate fracture-dislocation (Salter–Harris I or II) when seen in patients younger than 25 years of age when the growth plate of the medial end of the clavicle finally closes. Patients’ complaints typically range from a mild aching during overhead activities to a severe and disabling resting pain with impaired function and rapid fatigability of the shoulder girdle and upper limb. Backpacks or other devices with shoulder straps often cause discomfort. In ~30% of patients symptoms of brachialgia are present.9,10 Brachialgia is defined as a paresthesia or any numbness in the arm with or without associated muscle weakness. Usually, this involves the medial aspect of the arm. With the subcutaneous position of the clavicle, patients with midshaft clavicle nonunion do not generally require extensive diagnostic evaluation. The defect is often easy to palpate and motion and/or crepitus (usually painful) are obvious. The medial fragment is usually more prominent because of the downward pull on the lateral fragment. Often there are altered shoulder mechanics secondary to pain or malposition, resulting in a characteristic “drooping” or “ptosis” of the shoulder.10 More difficult is the diagnosis of a medial or lateral clavicle nonunion, as these injuries can often mimic ligamentous injuries and/or dislocations. Figure 2–1 Brachialgia is relatively common in patients with a (most often) hypertrophic midshaft clavicle nonunion. The medial cord of the brachial plexus is impinged upon by the nonunion. It is also important to perform a careful neurological examination as the subclavicular area contains not only the brachial plexus, but also the subclavian vessels. Neurovascular symptoms may range from mild dysesthesias or paresthesias to a full-blown thoracic outlet syndrome. Deficits in sensory and motor function of the shoulder and arm as well as vascular deficits should be documented. Brachial plexus palsies secondary to clavicle nonunion most often affect the medial cord, producing mostly ulnar nerve symptoms. The nonunions that are associated with brachial plexus palsies are most often hypertrophic and located in the midshaft where the medial cord crosses the clavicle (Fig. 2–1). Plain anteroposterior (AP) radiographs generally are sufficient for radiographic diagnosis. Both the medial and lateral ends of the involved clavicle should be visualized on this film to rule out any associated pathology of the AC and/or the sternoclavicular (SC) joint. In case of shortening, an AP radiograph of both clavicles will allow determination of the length that must be regained. To better visualize the AC joint and lateral clavicle, a Zanca-view (aiming 15 degrees cephalad) can be helpful. Computed tomography (CT) and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are seldom indicated, although for lateral and medial clavicle and/or SC injuries, a CT can better clarify intraarticular extension. Also, these methods may be helpful when dealing with a medial clavicle nonunion, which is often obscured by the sternum and ribs. Finally, MRI can be indicated when there is evidence of brachial plexopathy to precisely document the relationship between bone and brachial plexus. In addition to preoperative laboratory tests, we also obtain an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), and a complete white cell count to help rule out infection. We do not generally aspirate the nonunion to rule out infection at the site prior to surgery. Nonoperative treatment is seldom warranted. Although there are some anecdotal reports on the success of ultrasound on stimulating healing in a clavicle nonunion, we do not have any experience with this or other related techniques. Position the patient supine in the beach-chair semisitting position. A useful option is to use a Mayfield headrest rather than the standard broad headpiece of an operating table. The clavicle region and arm should be draped free so that the arm is freely mobile. The procedure can be done under interscalene block, but most often we use general anesthesia. This also allows harvesting of iliac crest bone graft. The head of the patient is turned away from the side of the clavicle that is to be operated upon, with the endotracheal tube positioned out the opposite corner of the mouth to maximize the operative field. Harvesting iliac crest bone from the same side is advantageous in terms of postoperative pain control, but using the contralateral iliac crest will allow two surgeons to work simultaneously. Figure 2–2 Optional plate positions: (A) superior, (B) wave-plate, and (C) anteroinferior. Depending on the preferred plate position (anteroinferior,3,11 superior,9,10 or wave plate9) (Fig. 2–2), the incision runs parallel to Langer’s lines along the superior or inferior border of the clavicle overlying the nonunion. In case of a previous incision, we try to incorporate this into our incision. The incision is carried down to bone. Although others describe loupe dissection and preservation of the (cutaneous) supraclavicular nerves, we do not specifically isolate or protect these nerve endings.10 In our experience, we have not had any postoperative complaints of dysesthesias or neuromas in the region of these nerves. Once the nonunion is identified there is often a significant amount of intervening soft tissue and scar with displacement of the bony ends. With the underlying neurovascular components occasionally encased in this fibrotic tissue, it is much safer to proceed with the dissection from known to unknown territory. Using careful dissection the soft tissues are gently pried of the anteroinferior or anterosuperior (depending on the plate position you anticipate) aspect of the bony ends working toward the nonunion. At the level of the nonunion extending to ~1.5 cm on either side we decorticate using a sharp osteotome. This should be done with caution, taking care to avoid any potential damage to the anterior divisions of the brachial plexus and the subclavian vessels. Most surgeons place the plate on the superior aspect of the clavicle, and are strengthened in doing so by most reports that argue that the tension side of the nonunion is the superior aspect of the clavicle. The forces of distraction acting on the bone are thus converted into compression acting as a tension band.10 Recently, the placement of the plate on the anteroinferior side has been described.3,11,12 The arguments in favor of this position are that the lateral fragment is often osteopenic and is now buttressed (like a shelf) by the plate rather than being suspended from it. In addition, screw length can be longer with a larger diameter from anteroinferior to superoposterior, and there is less risk of penetration of the drill into the subclavian neurovascular structures as opposed to drilling from superior to inferior. If placing the plate on the superior aspect, no dissection should be done on the anteroinferior side and vice versa. Deep tissue cultures are obtained and intravenous antibiotics can now be given. The next step is based on the type of nonunion. In case of a hypertrophic nonunion

Classification

Patient Assessment

History

Physical Examination

Radiologic Evaluation

Laboratory Studies

Treatment

Nonsurgical Treatment

Surgical Treatment

Midshaft Clavicle Nonunion

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree