Chapter 57 Mortality in SLE

Survival Rates in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Five-Year Survival

The 5-year survival rate for patients with SLE, which was as low as 50% in the report of Merrell and Shulman1 in 1955, varied between 64% and 87% in the 1980s, and it is fairly consistently reported to be approximately 95% today.2–4 Some of the increase in the rate of survival is simply a reflection of the improvements in health and survival in developed nations; between 1965 and 2005, mortality rates decreased by at least 70% in the general population.5 In the United States, the age-standardized death rate from all causes combined decreased from 1242 per 100,000 patients per year in 1970 to 845 per 100,000 patients per year in 2002. The largest percentage decreases have been in death rates from heart disease and stroke, which, as of the turn of the century, remain the two greatest causes of death.

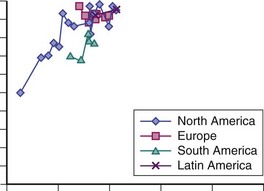

Figure 57-1 illustrates 5-year survival estimates in studies published from the 1950s to the present. These data are consistent with a plateau for short-term survival, at least for patients of European and North American descent. In fact, of the studies featured in Figure 57-1 (n = 33), most are from North America (n = 17) or Europe (n = 9) (two each from Sweden and England and one each from Denmark, Finland, Holland, Norway, and Spain). Only five studies are from south Asia (one each from Malaysia and Singapore and three from India) and two studies from South American centers (one from Chile and one from the multinational Grupo Latinoamericano de Estudio del Lupus [GLADEL] group). The paucity of data from outside North America and Europe makes it hard to judge how comparable 5-year mortality rates are for patients with SLE in less developed parts of the world (e.g., south Asia). In addition, the background variability in average life expectancy should be kept in mind; for example, in a country such as India, the average life expectancy is 65 years, whereas it is 80 years in North America and Europe.

One additional point: even in North America, ethnic factors play a role in SLE survival. This fact is best illustrated in the 5-year survival data from a study published by Alarcón and colleagues in 2001, which studied a cohort with a large proportion of ethnic minorities (i.e., African American, Hispanic) in whom 5-year survival was only 86%. Most alarming is the fact that this lower survival rate was actually less than what had been reported a decade earlier in more predominantly Caucasian SLE cohorts.6 In general, Caucasians have a better outcome than non-Caucasians, with mortality rates being several times higher in non-Caucasians than in Caucasians.7–9

As in patients with SLE of Hispanic descent, the rates of mortality from SLE in African Americans have been shown to be higher than the rates of mortality from SLE in Caucasian Americans on the basis of death statistics, but this is, in part, related to the threefold higher SLE prevalence in African Americans.10 Rothfield’s group reported trends in National Center for Health Statistics data from 1968 to 1991, during which SLE mortality among African Americans rose more than 30% since the late 1970s to a mean annual rate of 18.7 SLE deaths per million.11 Among female Caucasians, the total SLE mortality was reported to be stable from the late 1970s to 1991, averaging 4.6 deaths per million annually. A limitation of these types of data is that SLE may be underreported as a cause of death on death certificates; in any case, this underreporting is most pronounced in non-Caucasian populations12; thus the differences in these trends are likely real.

The interpretation of Rothfield’s group was that the observed trends were largely the result of the higher prevalence of SLE among African-American women than had been previously recognized, or the existence of barriers to diagnosis and effective treatment, particularly for young African-American women, or both. These barriers may include the presence of more resistant disease (e.g., lupus nephritis that is more likely to progress to end-stage renal failure [ESRF], regardless of treatment) in African Americans13; greater co-morbidity, especially hypertension, diabetes, and obesity; and/or problems with adherence or other social problems that may contribute to poor access to health care and increased mortality (including substance abuse and violence).14,15

These concerns are now widely recognized to affect patients from other African backgrounds and patients from other ethnic minorities in many parts of the world. These patients have been shown to have increased incidence and prevalence of lupus and worse outcomes, particularly increased mortality. The underlying reasons are multifactorial in nature and are likely to include genetic predisposition, although at least some of the mortality risk is likely to be modifiable.16

Canadian data suggest a similar scenario for patients with SLE of First Nations (i.e., indigenous North American) descent. In Peschken’s landmark population-based study from Manitoba, not only was there a twofold increased prevalence of SLE in those of First Nations descent versus Caucasians, but patients with SLE of First Nations descent had higher Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI) scores at diagnosis, had more frequent vasculitis and renal involvement, accumulated more damage, and experienced fourfold higher mortality rates, compared with non–First Nations patients with SLE. However, despite Canada’s theoretically “universally accessible” health care system for its citizens, First Nations Canadians are known, in general, to have considerable barriers to optimal health outcomes at all levels as a result of the problems with access to care, high co-morbidity (especially hypertension, diabetes, and obesity), and/or the same previously noted problems with adherence and/or other social problems that contribute to mortality, especially substance abuse and violence.17 For these reasons, First Nations patients have a much higher mortality rate than others.

Standardized Mortality Rates in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

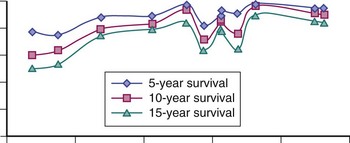

In a single-center North American study based in the very large cohort (n = 1175), Urowitz and colleagues18 demonstrated improved mortality risk in patients with SLE over a 36-year period between 1970 and 2005. The age- and sex-adjusted SMR decreased from 12.6 in the 1970s (95% confidence interval [CI] 9.1, 17.4) to 3.5 (95% CI 2.7, 4.4) by the end of the observation interval. In a very large (n = 9547) multicenter international SLE cohort, Bernatsky and associates19 found similar trends for improving mortality in patients with SLE, compared with the general population.

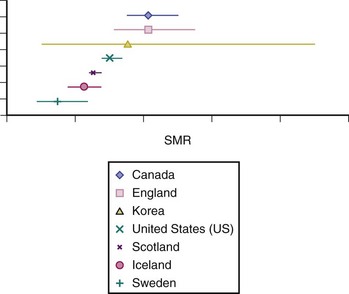

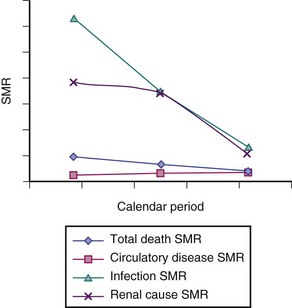

From this study, the relative risks for death as a result of infection or renal causes in patients with SLE versus the general population were very high in the 1970s (Figure 57-3). These findings emphasize the high relative risks for death related to these causes in those with SLE, which, in the general population, are relatively uncommon. Regarding this multicenter international mortality study, none of the centers contributing data were from developing nations, and, in general, most of the overall SMRs for the period under study did not substantially differ from one country to the next (Figure 57-4).

FIGURE 57-3 Unadjusted standardized mortality rate (SMR) estimates by calendar period.

(Data from Bernatsky S, Boivin J, Manzi S, Ginzler E, Gladman DD, Urowitz MB, et al: Mortality in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 54(8):2550–2557, 2006.)

It should be noted, however, that the rather encouraging findings presented (see Figures 57-1 and 57-2) do not take into consideration that subpopulations of patients with SLE, such as those with serious organ involvement (to be discussed in greater detail later in this chapter), may not enjoy the phenomenon of longer survival that is apparent for SLE overall. In fact, some of the apparent improvement in the 5-year survival rate in SLE (globally, as a disease) may relate to the fact that patients with milder SLE may be more recognized, and therefore more recent estimates arise from patient pools that include such mild cases. Although plausible, this premise is not proven. As discussed in the following text, however, it has been very well demonstrated that patients with more severe SLE most certainly still suffer higher mortality risks, relative to the general population.

Causes of Death in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Data, to date, emphasize the importance of renal disease, severe lupus disease activity, infection, and cardiovascular disease.20 Before the advent of effective SLE treatment, progressive disease activity, including renal failure and its associated complications, was one of the most important causes of death for patients with SLE. The exact attribution of lupus as a cause of death can be problematic; most authors have specifically included deaths as a result of renal failure in this category.

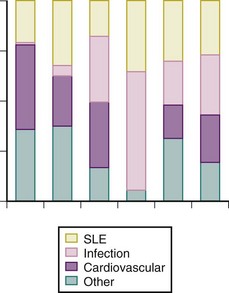

The incidence of renal failure was as high as 36% in one dataset from the 1960s,21 with SLE being the most common cause of death in some early data from North America. Deaths from lupus, although fortunately are considerably less common in at least developed countries, remain a problem. The mortality data from five large pools of patients with SLE published in the past 10 years (the study from Sweden was published in 2003 but the observation interval ended in 1995) show that SLE is still the cause of death for approximately 25% or more of people affected by the disease (Figure 57-5), possibly suggesting an increase in the proportion of deaths attributable to infection, which could reflect a greater use of immunosuppressive agents over time. However, the ability to compare the data is limited by the different methods for outcome ascertainment (e.g., whether it is through chart review or administrative data sources); these methods may be more or less sensitive for the determination of particular causes of death.

Deaths as a result of infections remain a grave concern, because they should be preventable or treatable (see Figure 57-5). The earliest reports of causes of death in those with SLE from 70 years ago noted that most patients died from infections; however, these reports were published during the preantibiotic era. Data actually suggest deaths in SLE as a result of infections have decreased, at least in developed countries, which is best demonstrated by the decrease in SMRs related to infection over time (see Figure 57-3). In the early years, this improvement probably reflected the increasing availability of antimicrobial medications and the effective recognition and treatment of infectious complications. In recent years, however, this decrease in the relative risk of death in SLE from infection may also be the result of the evolution of strategies that limit the incidence of infections when immunomodulatory therapy is used; for example, by limiting cumulative exposure and ensuring that immunization protocols are used. Although Mok and associates22 reported a trend to fewer deaths from major infection in patients with SLE of Chinese descent between the years of 2000 and 2006, a recent publication on 5243 patients with SLE assembled from Hong Kong administrative (hospitalization) records reported that infection continued to be an important cause of death.23

Infectious disease still contributes greatly to mortality and has been highlighted in other data as well. In a recent update of outcomes in a large multicenter, multinational inception cohort of SLE that began in 2000, 30 patients out of 1593 (89.4% women, average age at SLE diagnosis 34.6 years) died during the mean follow-up of 3.7 years, and the most common causes of death were infections (nine), SLE (nine), and coronary artery disease (CAD) (seven); the cause of death was not established in four patients.24 Of note, the GLADEL group reported that active disease and infection often co-existed and that both may have contributed to the deaths of some patients with lupus. For all these reasons, physicians should remain aware of the importance of serious infections in SLE-related mortality.

Currently, cardiovascular disease is the other primary cause of death in SLE, although in the large GLADEL (Latin American) group, no deaths were attributed to cardiovascular disease (see Figure 57-3). Demographics may be the reason; the GLADEL patient sample was only 41% Caucasian (compared with the other studies illustrated in Figure 57-3, which were predominantly Caucasian), with an age distribution that was likely younger than the other samples.

Early work by Urowitz and others first drew attention to the importance of mortality as a result of circulatory disease in SLE, particularly late in the disease course. Previous work by Manzi and colleagues25 has shown a very high incidence of cardiac events (specifically, myocardial infarction and angina) in patients with SLE, compared with those in the general population.

In developed nations like the United States, the greatest contributions to improved mortality in the past 35 years have been decreases in death rates from heart disease and stroke, which still, as of the turn of the century, remain the two greatest causes of death.5 However, data from the multicenter cohort study of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) (see Figure 57-3) show that despite a 60% decrease in the SMR estimates overall, as well as a decrease in deaths related to lupus activity, such as renal disease, the trend for circulatory disease shows no such decline. This finding has been suggested as well by Bjornadal and colleagues.26

These findings may reflect, in part, the complex nature of cardiovascular disease in SLE. Classic atherosclerosis risk factors, such as hypertension and hypercholesterolemia, do play a role, although recent work has suggested that additional risk is conferred by some disease-related characteristics, such as SLE duration and, perhaps, severity.27 However, other elements, such as medication exposures, may alter atherosclerosis risk in those with SLE. The specific role of steroidal drugs in SLE-related mortality is still debated, but hopefully data from currently ongoing large prospective cohorts will offer more insights as time goes on.

Active central nervous system (CNS) lupus is obviously another type of serious organ involvement that can potentially lead to death in SLE and was reportedly a common cause of death in early series, accounting for as much as 26% of the deaths reported by Dubois in the United States in 1956.28 This is no longer the case. In recent decades, CNS disease accounts for approximately 5% of deaths in SLE,29 with many of these events being vascular (i.e., hemorrhagic or thrombotic stroke) and not necessarily inflammatory disease in nature. In fact, establishing the underlying pathologic events from mortality reports is often difficult. Vital statistics data from a large Canadian pool of patients with SLE showed a large increase in ill-defined cerebrovascular events, which the authors suggested might represent cases of cerebral vasculitis or other rare forms of CNS disease.30 However, the alternative view is that this may reflect diagnostic uncertainty regarding the causes of some of the clinical presentations observed in patients with SLE.

Finally, malignancy is a common cause of death in the developed world, and the cancer risk profile in SLE is, of course, very interesting. In the SLICC multicenter international cohort study, a trend toward lower total cancer mortality risk in SLE was actually revealed, relative to the general population (SMR of 0.8, 95% CI 0.6 to 1.0).19 However, for mortality from hematologic cancers, the risk was elevated in SLE, compared with those in the general population (SMR of 2.1, 95% CI 1.2 to 3.4). This was also true for death from non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) (SMR of 2.8, 95% CI 1.2 to 5.6) and lung cancer (SMR of 2.3, 95% CI 0.6 to 3.0). This apparent discrepancy may be due to the fact that although the incidence of NHL in SLE is known to be elevated, it remains a much less common cancer than other malignancies, such as breast cancer. In fact, new evidence supports the premise that women with SLE actually have a decreased incidence of breast cancer! Thus this decreased risk of a relatively common malignancy, breast cancer, in women with SLE may very well drive the total decreased mortality risk for cancer in SLE.

Co-Morbidities as Predictors of Overall Mortality in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Cardiac Disease

In the very large multicenter multinational inception SLE cohort, a project begun a decade ago by the SLICC,31 patients who died had CAD more often at enrollment.24 Similarly, CAD was a predictor of death (as a result of any cause) in the multivariate hazard ratio (HR) analyses of Urowitz and colleagues,18 performed on a long-term cohort of prevalent patients with SLE. In this study, the HR for death in patients with CAD, compared with those without CAD, was 1.52, 95% CI 1.02 to 2.26. Of course, patients with CAD are intuitively at a heightened risk for mortality, compared with those who do not have CAD.

In data from the SLICC inception cohort, patients who died had higher SLICC/ACR damage index scores at enrollment, as compared with patients who remained alive at the end of the observation period. In large part, these higher index scores are likely the result of cardiac events, because (as previously mentioned) preexisting cardiac disease and established renal dysfunction are both strongly associated with mortality even in the general population.32 Recent data from Toronto18 and California33 support correlations between both these types of organ damage and the high risk of mortality.

Additional interesting information regarding co-morbidity and death in SLE has been generated from studies focusing on hospitalization data. In one comparison of women with and without SLE who were hospitalized for a cardiovascular event, women with SLE were significantly younger at the time of their hospitalizations. Moreover, of those who died during hospitalization, the patients with SLE were appreciably younger than the comparator group of women who died during hospitalization. This was especially true for African-American women34 and was interpreted by the authors as emphasizing again the high burden of cardiovascular disease in SLE, which heightens mortality risk.

Interestingly, one study suggested that suboptimal control of infectious complications was a major risk factor for death in patients with SLE undergoing admission into intensive care units.35 Ward and associates36–38 have also pointed out that outcomes for such patients were best if the care was provided at a tertiary center, where specialists were familiar with a relatively large volume of patients with SLE.

Renal Disease

Without a doubt, ESRF is also a major risk factor for death in SLE, as is true in the general population.39 In the University of California Lupus Outcomes Study,33 with concomitant adjustment for clinical and demographic information, the clinical covariate most associated with increasing risk for mortality was ESRF (HR 2.1, 95% CI 1.1 to 4.0). Based on data from the LUMINA (LUpus in MInorities: NAture versus nurture) multiethnic U.S. cohort, Alarcón’s group noted that renal damage was actually the item in the SLICC/ACR damage index that was of greatest predictive value in terms of mortality,40 although when the regression model included a variable capturing poverty, the finding was attenuated, suggesting that socioeconomic status (SES) may be as important a factor (or more so) or that SES and renal damage are greatly correlated, which, given what is already known of the effects of SES and outcomes in SLE, is likely important.

For patients with ESRF, predialysis co-morbidity (especially cardiovascular disease) is an important predictor of mortality.41 In fact, even in the general population, cardiovascular disease is recognized as a key element of co-morbidity for patients on dialysis.42 Thus specialists who care for patients with SLE and ESRF must carefully consider cardiac risk factors and treat these appropriately, although no specific data regarding the impact of such vigilance exist. It has been emphasized that even moderate uncontrolled hypertension worsens the clinical outcome in patients with ESRF, compared with those in the general population, which is often because of a heightened cardiac risk.43

Other Important Baseline Factors: Demographics, Organ Involvement, and Medications

Demographics: Sex, Age, and Socioeconomic Status

Several authors have suggested greater mortality in male than in female patients with SLE, when comparing survival rates by sex within the SLE population.6,7 However, these analyses did not often calculate mortality rates relative to the general population. The longevity of men is generally lower than that of women; thus in a comparison of the effect of sex on mortality in patients with SLE, using a parameter such as the SMR is preferable. In fact, Urowitz and associates18 in their 2008 publication demonstrated a trend for slightly lower sex- and age-specific SMRs for men with SLE (SMR of 3.96, 95% CI 2.90, 5.40) versus women (4.69, 95% CI 4.04, 5.45).

Similarly, the SMR provides a clearer understanding of which age group of patients with SLE has the greatest increased risk (compared with counterparts in the general population), since mortality rates in the general population increase with age. The study published in 2006 based on the SLICC international multisite cohort calculated a particularly high SMR of 19.2 (95% CI 14.7 to 4.7) for patients with SLE aged 16 to 24 years. In the study’s multivariate hierarchical regression models to determine independent effects of the factors examined (e.g., sex, age group, SLE duration, calendar-year period of SLE diagnosis, country) on the relative SMR estimates among patients with SLE, both younger age and female sex were associated with increased risk of death among the patients with SLE, relative to the general population. The longitudinal cohort of 957 adult subjects with SLE from the University of California Lupus Outcomes Study33 also generated evidence of a high relative risk for death in patients with SLE, aged 19 to 34 years, in whom the SMR was 20.4.

Regarding factors such as SES and education, the longitudinal cohort from the University of California Lupus Outcomes Study also showed that with concomitant adjustment for clinical and demographic information, the demographic covariates most associated with increasing risk for mortality included low education (HR 1.9, 95% CI 1.1 to 3.2).33 Ward and others44 also found that, among Caucasians, higher education levels were associated with lower lupus-related mortality.

Studenski and colleagues45 found that the non-Caucasian race and SES both contributed independently to mortality. In fact, the overall improved survival in Caucasians versus African Americans in one report was primarily attributed to differences in SES, which was lower among the African Americans.46 A publication from Kasitanon and colleagues47 in Baltimore demonstrated that patients with an annual family income of less than $25,000 had poorer survival (adjusted HR = 1.7).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree