41

Metacarpal Neck Fractures

Kostas J. Constantine and Thomas R. Kiefhaber

History and Clinical Presentation

A 20-year-old man was involved in a street brawl, in which he swung at but missed his opponent and struck a wall, causing immediate pain and swelling of his dominant right hand. Two days later, he presented to the emergency room complaining of continuing discomfort despite ice and elevation.

Physical Examination

Swelling and ecchymosis were noted, centered over the dorsal ulnar half of the hand. When viewed dorsally, the fifth metacarpal head lacked the prominence of the other digits. Tenderness was maximal at the fifth metacarpal neck, and palmar palpation revealed fullness at the level of the metacarpophalangeal (MP) joint. When the patient was asked to actively extend his small finger, the MP joint hyperextended 5 degrees, but he was unable to fully extend his proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint (minus 20 degrees of full extension). When the patient made a fist, the small finger rotated toward the thenar eminence and was overlapped by the ring finger. There were no open wounds, and no other areas of tenderness localized. Two-point discrimination and vascular status were intact.

PEARLS

- Acceptable reduction:

Index/long <10–15 degrees

Index/long <10–15 degrees

Ring/small <30-40 degrees (up to 70 degrees if greater than 10 to 14 days)

Ring/small <30-40 degrees (up to 70 degrees if greater than 10 to 14 days)

- If apex-dorsal angulation is greater than acceptable, attempt closed reduction using Jahss maneuver.

- If unstable reduction, malrotation, or pseudoclawing, and less than 10 days postinjury, operative percutaneous pinning is indicated.

- Open reduction is rarely indicated, but may be necessary and should allow for early range of motion.

PITFALLS

- Examine for malrotation or pseudoclawing on extension.

- Do not splint in the Jahss position because of risk of PIP flexion contracture and skin necrosis.

- If concerned about stability, follow radiographs closely the first 2 weeks after closed reduction and splinting.

- Incision and drainage should be done for any wound over the MP joint, and it should be left open.

Differential Diagnosis

Metacarpal neck fracture

Other metacarpal/proximal phalangeal fracture

Metacarpophalangeal dislocation

Metacarpophalangeal joint infection

Sagittal band/extensor tendon/collateral ligament injuries

Diagnostic Studies

Diagnostic Studies

Posteroanterior, lateral, and oblique radiographs revealed a fifth metacarpal neck fracture with 60 degrees apex dorsal angulation and volar comminution (Fig. 41–1). No other abnormalities were noted.

Diagnosis

Fifth Metacarpal Neck Fracture (“Boxer’s Fracture”)

The mechanism of injury, examination, and radiographic findings confirm the diagnosis of a fifth metacarpal neck (or “boxer’s”) fracture. When applied to the fifth metacarpal, “boxer’s fracture” is a misnomer because professional fighters are more likely to fracture their index and middle metacarpal necks. Breaking the small or ring metacarpal neck is more often seen in weekend pugilists who use poor boxing technique.

The metacarpal neck is the most common site of fracture resulting from a clenched fist blow. Apex dorsal angulation occurs as a result of three factors:

- The volar moment arm of the intrinsic muscles flexes the metacarpal head.

- The force vector causing the fracture is from a dorsal to palmar direction.

- Invariably, there is some degree of volar comminution at the fracture site.

Nonsurgical Management

In discussing the degree of metacarpal neck angulation that can be accepted after fracture, the index and middle fingers, with their relatively immobile carpometacarpal (CMC) joints, must be considered separately from the ring and small digits. Most surgeons agree that the index and middle fingers should not be left with more than 10 to 15 degrees of residual angulation.

The CMC joints of the small and ring fingers travel through a 35-degree flexion arc, which allows patients to tolerate larger amounts of flexion deformity without functional disability. The amount of acceptable metacarpal neck angulation for these digits, therefore, is controversial. The controversy is exemplified by the multitude of conflicting recommendations found in the literature.

Several authors support accepting apex dorsal angulation up to 70 degrees, whereas others tolerate only 20 degrees. Hunter and Cowen found that angulations as large as 70 degrees could be tolerated with no compromise of hand function. Other published reports suggest patient dissatisfaction with angulation greater than 20 to 30 degrees secondary to the loss of knuckle prominence and palmar discomfort when grasping objects that abut the flexed metacarpal head. As a practical compromise, most surgeons prefer apex dorsal angulations for the ring and small metacarpal necks to be less than 30 to 40 degrees, with no malrotation and no pseudoclawing (MP hyperextension with PIP extensor deficit). Delayed presentation or loss of reduction may necessitate accepting 70 degrees of angulation and then treating the rare symptomatic patient with a corrective osteotomy.

Boxer’s fractures should be treated with a closed reduction if the fracture is still mobile (less than 10 to 14 days old) and the following criteria are met:

- Angulation greater than 30 to 40 degrees (ring or small finger)

- Rotational malalignment

- Pseudoclawing (MP hyperextension with PIP extensor deficit)

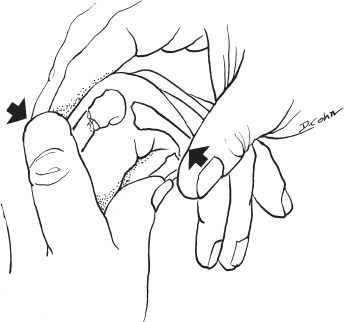

Perform the reduction under a metacarpal block, or, alternatively, an ulnar nerve block. The most commonly used reduction technique is the Jahss maneuver. The MP and interphalangeal (IP) joints are flexed 90 degrees to relax the intrinsic muscles and tighten the collateral ligaments. The metacarpal head is then reduced onto the shaft by exerting upward pressure on the distal head of the proximal phalanx, forcing the base of the proximal phalanx into the metacarpal head (Fig. 41–2).

Immobilization methods include ulnar gutter splints or circular casts. A closely molded gutter splint including an adjacent uninjured digit provides adequate immobilization while providing a safety margin to accommodate swelling. Immobilization is best accomplished by placing the wrist in 20 to 30 degrees of extension, the MPs in 80 to 90 degrees of flexion, and the IPs in extension. Radiographs should be checked within 1 week of immobilization to ensure no loss of reduction. Treatment is continued for 3 to 4 weeks. The patient is then allowed to begin active range of motion of the injured hand and wrist. For patients requiring additional support, protection by a removable P1 blocking Orthoplast splint (leaving the IP joints free) for an additional 2 to 3 weeks between exercises and at night is a viable option. Do not immobilize the fingers in the Jahss position used for closed reduction because of the risk of PIP flexion contractures and skin necrosis.