33

Acute Laceration of Flexor Tendons

Mark S. Rekant

History and Clinical Presentation

A 38-year-old right hand dominant musician presents to the office 4 days following a laceration to the volar surface of his right long finger sustained after a fall onto a broken piece of glass (Fig. 33–1). He complained of pain in the right long digit with inability to actively flex his finger. He also noted decreased sensation along the ulnar aspect of his finger. He had been working prior to the accident and wished to return to playing guitar as soon as possible. He denied any past medical history but did admit to smoking one pack of cigarettes per day.

He had been seen previously at a local emergency room where his laceration was irrigated and loosely sutured. Tetanus booster and a dose of intravenous antibiotics were administered. He was discharged with a protective finger splint.

Physical Examination

An oblique volar laceration was noted, beginning radially just proximal to the proximal interphalangeal joint extending ulnarly and distally 1 cm to the midaxial line of the right long finger. The patient demonstrated no active flexion of the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) or distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints. His two-point discrimination was greater than 15 mm along the ulnar border of that digit. The digit was warm, and had good color, turgor, and normal capillary refill.

PEARLS

- Use fine instrumentation, atraumatic technique, and loupe magnification.

- Ensure minimal gapping at the repair site with smooth juncture of tendon ends.

- Provide sufficiently strong repair to permit and institute early controlled mobilization.

PITFALLS

- Avoid excessive tendon handling during mobilization and repair.

- Avoid disrupting pulley system, especially A2 and A4.

- Avoid intruding or interfering with tendon vascularity.

Diagnostic Studies

Anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of the injured hand or forearm should be evaluated to ensure that no bony injury is overlooked and to investigate the possibility of a retained foreign body. No fracture was appreciated.

Figure 33–1. Patient’s finger at presentation.

Differential Diagnosis

Laceration of both flexor digitorum superficialis and profundus and digital nerve Laceration of either flexor tendon singularly with inability to move secondary to pain

No tendon laceration but unable to move secondary to pain

No nerve laceration but rather contused/neuropraxic

Diagnosis

Laceration of the Ring Finger Flexor Digitorum Profundus, Flexor Digitorum Superficialis, and Ulnar Digital Nerve to the Ring Finger

The repair of lacerated flexor tendons of the hand and their return to appropriate function is one of the most difficult and challenging tasks for a surgeon to undertake. Lacerations within zone 2 are especially complex. Within this area of the fibro-osseous digital canal, the profundus and superficialis tendons interweave in an intricate and close relationship. Even minimal swelling of the epitenon is sufficient to impair free motion of both tendons. The margin for error in tendon repair is thus very small in this region.

The necessity of minimizing adhesions can be a daunting charge. On the one hand, it requires nontraumatic treatment of the tendon, respecting the dorsally located blood support and, on the other, requires early motion, jeopardizing the continuity of sutures. This patient’s flexor tendons were repaired using a Tajimi technique with four strands of 4–0 polyester crossing the repair. Care was taken to avoid excessive handling of the tendons, with the tendon being grasped by forceps only once. Additionally, a 6–0 Prolene running epitendinous suture was used to minimize gapping and facilitate healing. The sheath was not repaired. No publication to date provides scientific evidence that sheath repair improves outcome. Although one may argue that reconstituting the sheath provides a barrier to adhesion formation, restores synovial fluid nutrition, and restores sheath mechanics, in practicality the synovial membranes are usually badly damaged and unsalvageable.

Gapping at the repair site results in weakening and, potentially, adhesion formation. Each increase in suture caliber strengthens the repair, nevertheless, at the cost of additional material interference. This additional material may compromise tendon vascularity and/or precipitate adhesion formation. Biomechanically, core sutures placed dorsally strengthen the repair; yet there is a fine line, as sutures placed too dorsal may compromise the tendon’s blood supply. Early motion should be begun. Stressed tendons heal faster, gain tensile strength faster, form fewer adhesions, and demonstrate better excursions (Table 33–1).

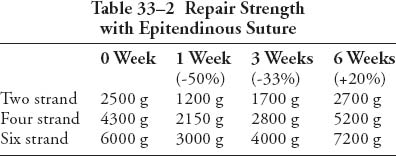

The surgeon must feel comfortable with his or her choice of techniques and suture material. These characteristics should lend themselves to easy placement of sutures in the tendon and the ability to place secure knots, afford minimal interference with tendon vascularity and gapping at the repair site, and provide sufficient strength throughout healing to permit the application of early motion stress to the tendon (Table 33–2).

| Passive motion | 500 g |

| Light grip | 1500 g |

| Strong grip | 5000 g |

| Tip pinch-index flexor digitorum profundus | 9000 g |

Preoperative Management

Initially the wound was irrigated with 1 L of normal saline. A tetanus booster was administered. The laceration was loosely closed with 4–0 nylon suture in an interrupted fashion. The hand was immobilized with a volarly placed plaster splint maintaining the wrist in 45 degrees of extension, the metacarpophalangeal (MP) joints near 90 degrees of flexion with full extension of the proximal and distal interphalangeal joints.

Surgical Management

The arm is exsanguinated with an Esmarch bandage and tourniquet inflated to 250 mm Hg. The use of 2 to 4 power loupe magnification greatly enhances one’s proficiency in performing flexor tendon repair, and small, precise instrumentation is a prerequisite for this type of surgical repair. As is necessary with every tendon laceration repair, the wound is extended in a Bruner type fashion both proximally and distally to provide a wide visibility of the injured area. Using mid-axial extensions places the digital vessels and nerves at unnecessary risk unless a concomitant injury is suspected. The incisions are extended as needed to visualize the lacerated ends of the tendon or tendons. An adequate view of the surgical field must be created to avoid carrying out delicate surgical repairs within the confines of a small, cosmetic wound. Dissection begins midline, over the tendon sheath, and then proceeds with identification of the digital nerves and vessels. If these structures, too, have been severed, the ends are mobilized and brought into proximity for subsequent suturing.

At this point, the laceration in the tendon sheath was identified at the C1 level (between A2 and A3). A window in the cruciate-sheath system is made by carefully excising this tissue. Additional windows may be necessary depending on the level of injury and positioning of the proximal and distal stumps. These should be fashioned as needed. However, great care is taken to preserve the annular components (especially A2 and A4), which are almost impossible to adequately repair.

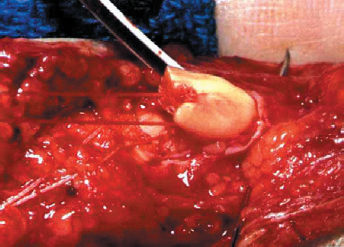

The distal stumps of the profundus and superficialis are delivered into the cruciate window by acutely flexing the DIP and PIP. Once the tendons are exposed in this manner, core sutures are placed in the superficialis and profundus and clamped for later usage (Fig. 33–2).