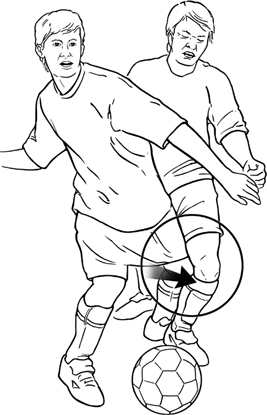

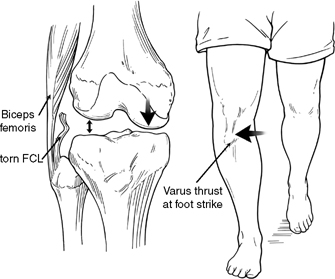

4 The usual mechanism of injury of the posterolateral corner involves a component of contact or noncontact twisting, hyperextension, or varus force due to athletic injuries, falls, or motor vehicle accidents.1–4 Historically, the main mechanism of injury has been reported to be a blow to the anteromedial aspect of the knee while the foot is firmly planted on the ground,1,3 which results in a varus or varus/hyperextension knee injury (Fig. 4-1). Although isolated posterolateral knee injuries would primarily occur due to a varus or posterolateral twisting mechanism, as it is at this position that increased stress is seen on the main static stabilizers of the knee,5–8 it is recognized that most posterolateral knee injuries occur in combination with other ligament injuries, as these mechanisms of injury often cause injury to other knee ligaments and not just the posterolateral knee structures. Müller9 noted that the popliteus tendon and the posterior cruciate ligament were parallel to each other, and that a tear of the posterior cruciate ligament was commonly associated with the posterolateral corner injury. The largest study population that recorded the mechanism of injury for posterolateral knee injuries (71 patients), reported that the most common mechanisms of injury were twisting (30%), noncontact hyperextension (21%), contact hyperextension (15%), an anterior blow to a flexed knee (10%), and a valgus force to a flexed knee (7%).4 In this study, only 28% of these injuries were isolated grade 3 posterolateral corner knee injuries, with the remainder occurring in combination with other knee ligament injuries.4 It is important to recognize that many different mechanisms cause injuries to the structures of the posterolateral corner of the knee. Therefore, in addition to understanding the history of the etiology of these knee ligament injuries, it is also essential to verify the integrity of the posterolateral knee via a thorough clinical examination. Figure 4-1 A classic mechanism of posterolateral knee injuries is a blow to the anteromedial aspect with the foot planted. A thorough history must be obtained in patients with posterolateral knee injuries. Patients with acute isolated, or combined, ligament injuries may complain of pain along the posterolateral aspect of the knee.4,10,11 Often, there is minimal swelling present, even in the face of an acute injury.4 In addition to a thorough history that attempts to ascertain the mechanism of injury and any subjective patient complaints of instability, a thorough examination of the patellofemoral and tibiofemoral joint for knee instability, compared with the normal contralateral knee, must be performed. Patients may also complain of numbness, dysesthesias, or distal motor weakness (including a footdrop) due to a neuropraxia or complete injury to the common peroneal nerve. It is especially important to determine the presence of these symptoms, even if transitory, as they may indicate that a significant varus or combined varus-rotational injury occurred to the knee. In addition, it is important to thoroughly document the neuromotor function of the common peroneal nerve prior to any surgical intervention so that postoperative circulation can be motor, and sensory follow-up exams are not confusing. Less than 50% of patients with a complete motor loss regain function over time, and it is important to discuss this frankly with patients at their initial presentation. Patients with posterolateral knee injuries frequently describe instability with normal level walking, turning while climbing flights of stairs, or twisting, pivoting, or cutting to the affected side of the knee. Although the more severe varus-thrust gait pattern is more commonly seen with combined concurrent cruciate ligament injuries, it also can be seen in some athletes with an isolated acute, or chronic, fibular collateral ligament tear and a constitutional varus alignment. I examined a high school varsity quarterback with an isolated fibular collateral ligament tear, with virtually no generalized pain or swelling of his knee after a varus-contact injury, whose varsity coach designed plays for him so he did not need to cut, pivot, or twist to his left (affected) side. He was able to run, although much less effectively, within 1 week of injury. He did play an additional 2 weeks before it was recognized that he had a serious problem as his instability became more noticeable and his overall function worsened. I have found it best not to ask leading questions but rather to have patients describe their instability pattern in their own words. Frequently they report a “side-toside toggling” of their knee, which helps me to recognize that they may have a posterolateral knee injury (Fig. 4-2). I have found that patients with isolated posterolateral knee injuries do not complain of instability going down stairs or down hills, whereas patients who have concurrent posterior cruciate ligament tears often do complain of it. However, it has been demonstrated that the posterolateral knee structures do have some role in preventing primary posterior translation near extension,6–8,12 so it is possible that a patient could complain of this problem in high-level activities involving descending.

Mechanism and Presenting History of Posterolateral Knee Injuries

Mechanism and Presenting History of Posterolateral Knee Injuries

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Full access? Get Clinical Tree