Chapter 27 Malignant Tumors of Bone

Osteosarcoma

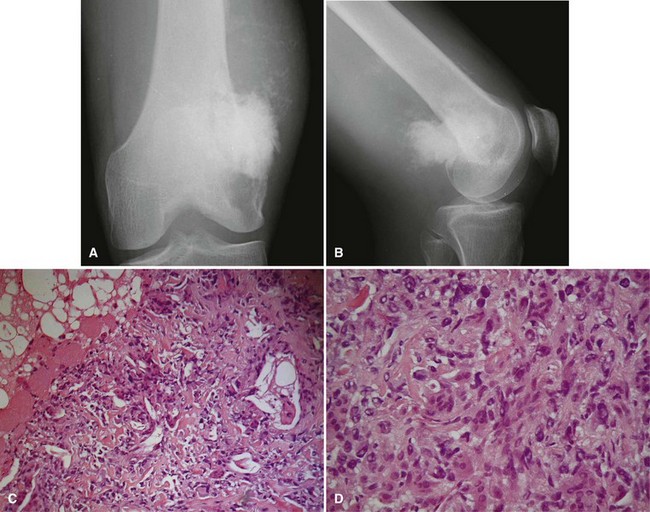

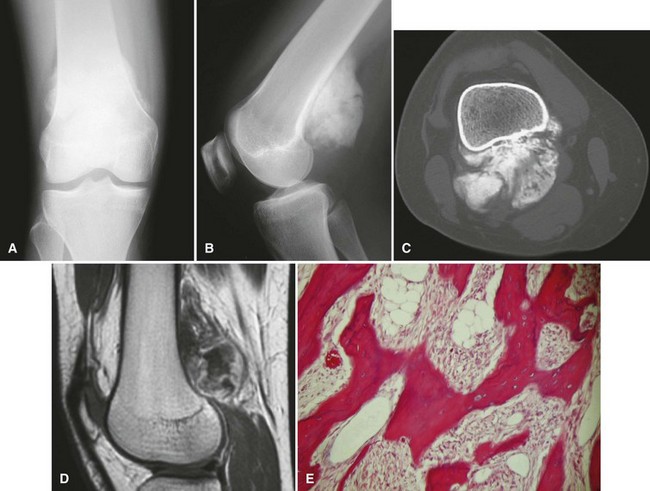

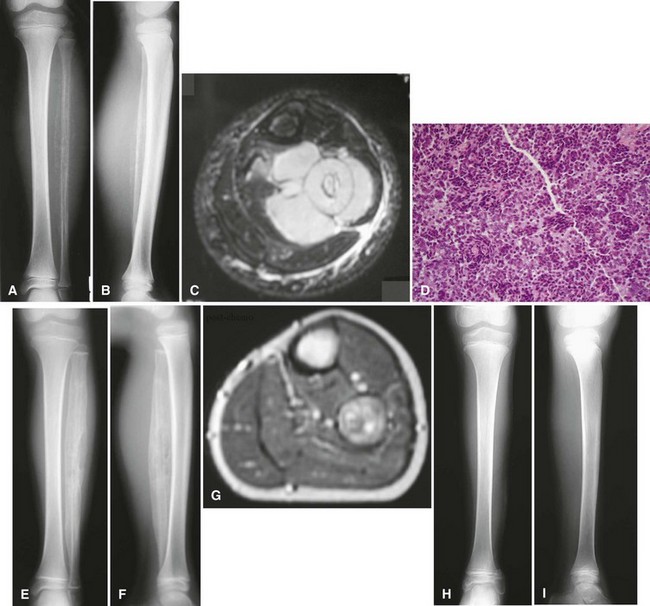

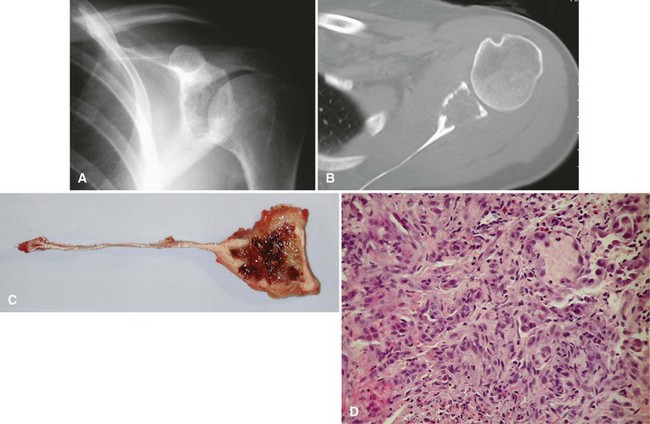

Most osteosarcomas are classified as conventional osteosarcomas (Figs. 27-1 to 27-3) and have a radiographic appearance as previously described. These high-grade tumors begin in an intramedullary location but may break through the cortex and form a soft tissue mass. Histologically, they may be primarily osteoblastic, fibroblastic, or chondroblastic; however, osteoid production from the tumor cells must be shown. The spindle cell component is high grade with hypercellularity, abundant mitotic figures, and marked nuclear pleomorphism.

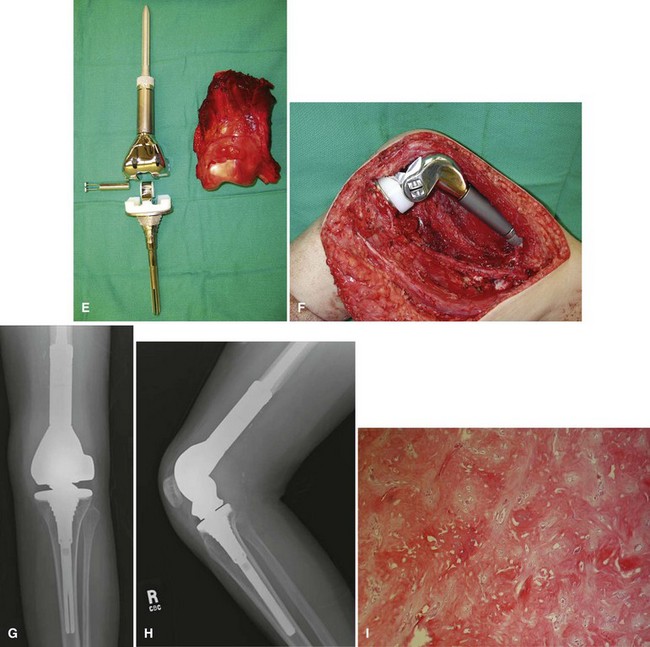

Periosteal osteosarcoma (Fig. 27-4) is an intermediate-grade malignancy that arises on the surface of the bone. The most common locations are the diaphyses of the femur and tibia. It occurs in a slightly older and broader age group. Histological examination of periosteal osteosarcoma shows strands of osteoid-producing spindle cells radiating between lobules of cartilage.

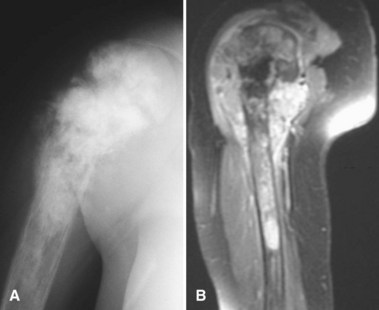

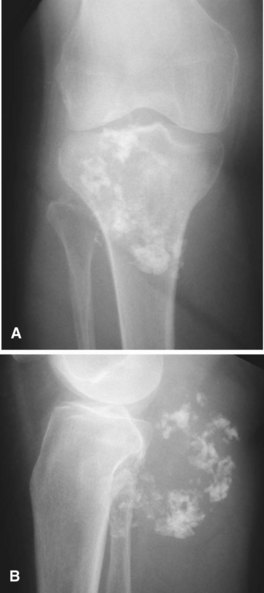

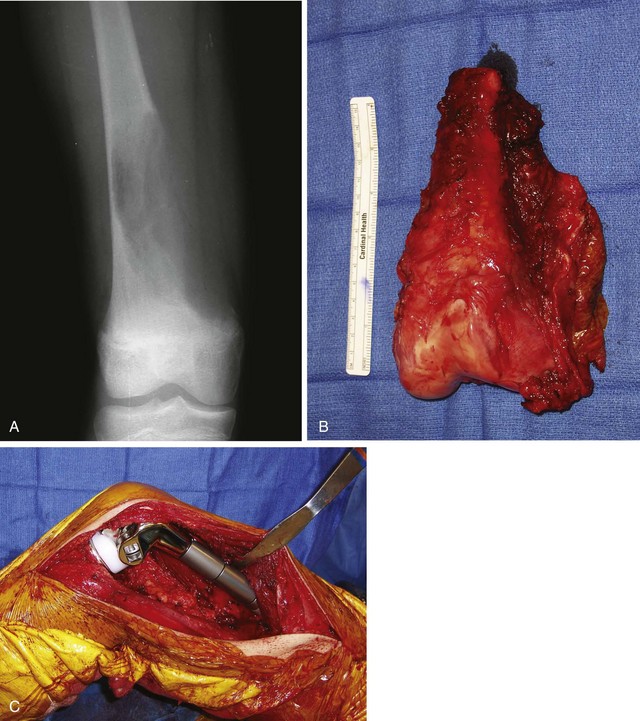

Parosteal osteosarcoma (Fig. 27-5) also is a rare, low-grade malignancy, but it arises on the surface of the bone and invades the medullary cavity only at a late stage. It has a peculiar tendency to occur as a lobulated ossified mass on the posterior aspect of the distal femur. CT may be helpful in differentiating this subtype of osteosarcoma from myositis ossificans or an osteochondroma. The ossification in myositis ossificans is more mature at the periphery of the lesion, whereas the center of a parosteal osteosarcoma is more heavily ossified. Parosteal osteosarcoma can be easily differentiated from an osteochondroma because the CT scan of an osteochondroma shows a medullary cavity containing marrow in continuity with the medullary canal of the involved bone. Microscopically, similar to a low-grade intramedullary osteosarcoma, parosteal osteosarcoma consists of slightly atypical spindle cells producing slightly irregular osseous trabeculae.

Chondrosarcoma

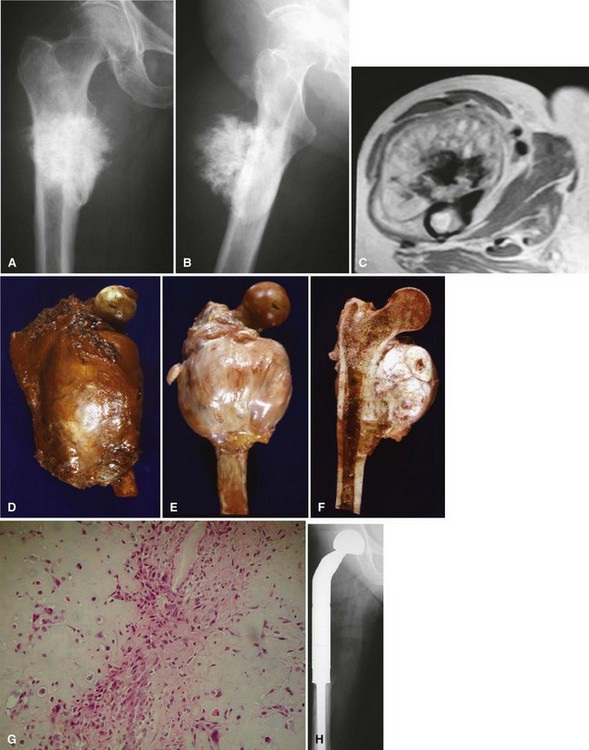

Secondary chondrosarcomas arise at the site of a preexisting benign cartilage lesion. They occur most frequently in the setting of multiple enchondromas and multiple hereditary exostoses. In Ollier disease (multiple enchondromas) the incidence of malignancy (most commonly chondrosarcoma) is approximately 25% by age 40 years, and in patients with Maffucci syndrome (multiple enchondromas with soft tissue hemangiomas) the incidence may be even higher. Although data for osteochondromas are difficult to analyze, the lifetime incidence of secondary chondrosarcoma is estimated to be 5% for patients with multiple hereditary exostoses and approximately 1% for patients with solitary osteochondromas (Fig. 27-6). As discussed in Chapter 25, the true incidence of malignant degeneration of osteochondromas is unknown. Published estimates are likely too high, owing to the effect of referral bias on pathology data at tertiary referral centers. The true prevalence of osteochondromas in the general population is unknown. Whether a solitary benign enchondroma has the potential to give rise to a secondary chondrosarcoma is difficult to determine. If this does occur, the incidence is not high enough to warrant prophylactic treatment of asymptomatic enchondromas. Other conditions that have been reported to be associated with secondary chondrosarcoma include synovial chondromatosis, chondromyxoid fibroma, periosteal chondroma, chondroblastoma, previous radiation treatment, and fibrous dysplasia.

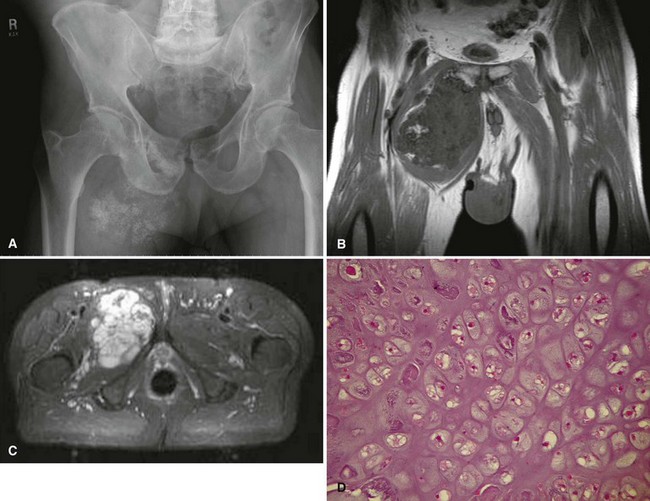

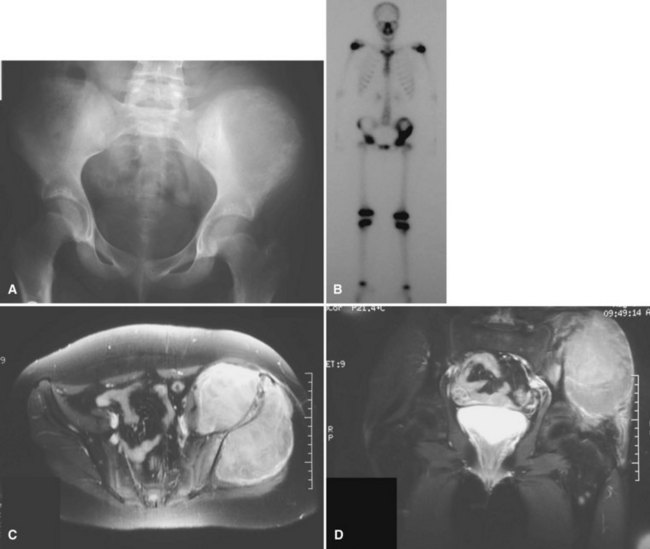

The radiographic appearance of chondrosarcoma frequently is diagnostic (Fig. 27-7). Similar to enchondroma, it is a lesion arising in the medullary cavity with irregular matrix calcification. The pattern of calcification has been described as “punctate,” “popcorn,” or “comma shaped.” Compared with enchondroma, however, chondrosarcoma has a more aggressive appearance with bone destruction, cortical erosions, periosteal reaction, and, rarely, a soft tissue mass. CT can be helpful to show endosteal erosions or other evidence of a destructive lesion and to differentiate benign from malignant cartilage lesions. The site of the lesion also must be considered because lesions in the hand (the most common site for an enchondroma and a rare site for a chondrosarcoma) may appear aggressive and still be diagnosed as benign. The same amount of cortical destruction shown in a pelvic or proximal femoral lesion would be diagnostic of a chondrosarcoma. Finally, the size of the cartilaginous cap of an osteochondroma, as evaluated with CT or MRI, is important in evaluating the possibility of a secondary chondrosarcoma. If the cartilaginous cap is larger than 2 cm in a skeletally mature patient, a secondary chondrosarcoma must be considered.

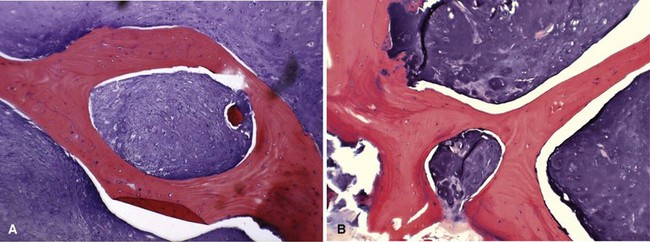

Histologically, conventional chondrosarcomas are composed of malignant cells with abundant cartilaginous matrix. (If malignant osteoid is present even in small amounts, the diagnosis should be chondroblastic osteosarcoma—a tumor with different prognostic and therapeutic implications.) Differentiating a low-grade chondrosarcoma from an enchondroma can be difficult solely from a biopsy specimen. Factors that favor a malignant diagnosis include hypercellularity, plump nuclei, more than occasional binucleate cells, a permeative pattern, and entrapment of bony trabeculae (Fig. 27-8). As much tissue as possible should be obtained from the biopsy of a borderline lesion. Perhaps in no other circumstance is correlation with the clinical and radiographic findings more important. Lesions in the setting of multiple enchondromas, periosteal chondromas, synovial chondromatosis, and enchondromas of the hand all may appear hypercellular and yet still can be benign. This same appearance in a biopsy specimen taken from a solitary large pelvic lesion with radiographically shown cortical erosions would be diagnostic of a chondrosarcoma.

FIGURE 27-8 Low-power (A) and high-power (B) photomicrographs of a chondrosarcoma demonstrate entrapment of trabeculae.

Less common histological subtypes of chondrosarcoma include dedifferentiated chondrosarcoma, clear cell chondrosarcoma, and mesenchymal chondrosarcoma. Together, these subtypes constitute less than 20% of all chondrosarcomas. Histologically, dedifferentiated chondrosarcoma consists of a high-grade sarcoma (most commonly osteosarcoma followed in frequency by fibrosarcoma and malignant fibrous histiocytoma) adjacent to an otherwise typical low-grade chondrosarcoma (Fig. 27-9). The radiographic features of a dedifferentiated chondrosarcoma often show a more aggressive radiolucent area juxtaposed on an otherwise typical chondrosarcoma.

Ewing Sarcoma

Ewing sarcoma is the third most common nonhematologic primary malignancy of bone, but it is the second most common (after osteosarcoma) in patients younger than 30 years of age and the most common in patients younger than 10 years of age. The incidence is less than 1 per 1 million per year, accounting for about 9% of primary malignancies of bone. Ewing sarcoma has been reported to occur in a wide age range of patients from infants to the elderly, but most occur in patients 5 to 25 years old. The most common locations include the metaphyses of long bones (often with extension into the diaphysis) and the flat bones of the shoulder and pelvic girdles (Figs. 27-10 and 27-11). Rarely, it occurs in the spine or in the small bones of the feet or hands. Similar to most sarcomas of bone, there is a slightly higher incidence in males. Ewing sarcoma is exceedingly rare in individuals of African descent. There are no known predisposing factors.

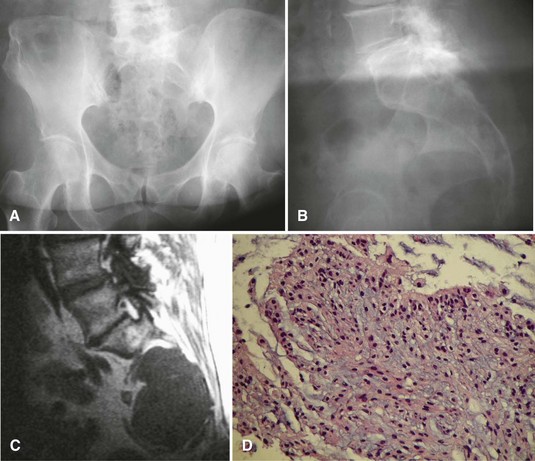

Chordoma

Radiographically, chordomas appear as destructive lesions (Fig. 27-12). They virtually always arise from the midline. Sacrococcygeal lesions often are missed on the initial radiographic examination because of overlying bowel gas. They usually are seen more easily on a lateral view of the sacrum. Likewise, radioisotope accumulation in the bladder can obscure a sacral tumor on a bone scan. More than 50% of chordomas exhibit radiographically detectable calcification. CT may be better for detecting calcification (which may help with the diagnosis), but MRI is better for determining the full extent of the lesion and its relationship to other anatomical structures. A common pitfall in the evaluation of a patient with a chordoma and low back pain is ordering an MRI of only the lumbar spine; this study usually misses a sacrococcygeal chordoma because most arise below S3.

Adamantinoma

The most common radiographic appearance is that of multiple, sharply demarcated radiolucent lesions in the tibial diaphysis (Fig. 27-13). The radiolucent lesions are separated by areas of dense, sclerotic bone. Although the radiographic appearance is similar to that of osteofibrous dysplasia, adamantinoma usually has a more aggressive appearance. A large portion or even the entire tibia can be involved. Frequently, the fibula also is involved by direct extension of the tumor.

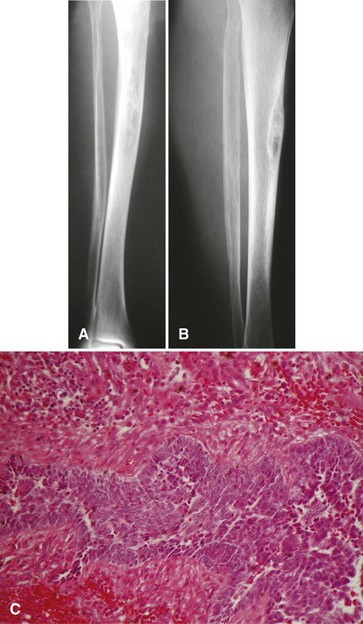

Malignant Vascular Tumors

Pain or, more rarely, pathological fracture is the presenting complaint. Duration of symptoms varies depending on the grade of the tumor. The radiographic appearance of this lesion also is correlated with its grade. Low-grade tumors appear as well-demarcated lytic lesions that may or may not have surrounding reactive bone formation (Fig. 27-14). High-grade tumors have a more permeative appearance. Periosteal reaction is unusual. Malignant vascular tumors have a peculiar tendency to be multicentric at presentation regardless of grade. Most commonly, multiple lesions are found within the same bone or within multiple bones of the same extremity.

Malignant Fibrous Histiocytoma and Fibrosarcoma

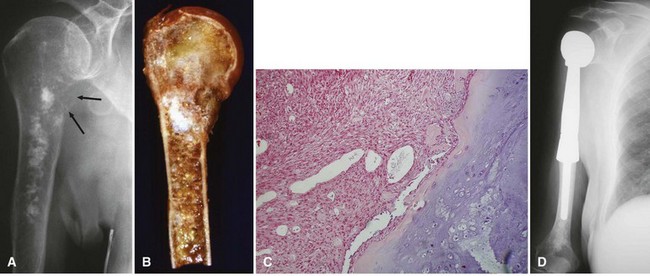

Malignant fibrous histiocytoma and fibrosarcoma of bone constitute 3% to 5% of primary malignant tumors of bone. Excluding the first decade, they occur at any age with comparable frequency. Males and females are affected equally. There is a slight tendency for the lesion to occur in the distal metaphysis of the femur or the proximal metaphysis of the tibia; however, any bone may be involved. Approximately 25% of these tumors are considered to be secondary to a preexisting bone abnormality. The most commonly reported predisposing conditions include Paget disease, radiation, giant cell tumor, and bone infarction (Fig. 27-15). They also may occur as part of a dedifferentiated chondrosarcoma.