29 The intervertebral disk (IVD) acts as a shock absorber between the bony vertebrae and makes up 25% of the total spinal column height. The IVD is composed of the “tougher” outer annulus fibrosus surrounding the “jelly-like” inner nucleus pulposus. The most common cause of a radiculopathy is compression of a nerve root from a herniated nucleus pulposus. Other less common causes of lumbar radiculopathy stem from degenerative (spondylolysis), neoplastic, infectious, and inflammatory origins. Lumbar radiculopathy can be debilitating. It manifests as leg symptoms that usually include pain, numbness, tingling, and, at times, weakness. Low back pain (LBP) may also be present, and patients may experience difficulties while walking, while sitting, and at rest. The most common spinal levels involved are L3–L4, L4–L5, and L5–S1. The natural history of lumbar radiculopathy is favorable, and nonsurgical management results in improvement in the vast majority of patients (up to 93%). If symptoms persist beyond a reasonable course of nonsurgical management or if neurological function deteriorates, then surgical intervention is indicated. IVD herniations can be classified into three types based on the location of the herniation (Table 29.1). Leg symptoms vary depending on the level, direction of the herniation, and corresponding nerve root affected. (Table 29.2). When a patient initially presents with radicular leg pain, a thorough history is critical. In addition to eliciting the onset, severity, and quality of the symptoms, aggravating and alleviating factors should be identified. Changes in bowel, bladder, or sexual function are important clues to dysfunction of the cauda equina (1–16% of operated lumbar disk herniations). Table 29.1 Disk Herniation Types

Lumbar Radiculopathy

![]() Classification

Classification

![]() Workup

Workup

Types | Leg symptoms |

Posterolateral | Unilateral, traversing nerve root |

Far lateral | Unilateral, exiting nerve root |

Central | Variable, but may affect bilateral traversing nerve roots or cauda equina |

Table 29.2 Disk Herniation Level, Location with Nerve Affected, and Leg Symptoms

Lower extremity symptoms/findings | |

L3–L4 Herniation | |

Posterolateral–L4 nerve root | Anterior leg symptoms |

Far lateral–L3 nerve root | Anterior thigh symptoms |

L4–L5 Herniation | |

Posterolateral–L5 nerve root | Back of leg/dorsum of foot symptoms |

Far lateral–L4 nerve root | Anterior leg symptoms |

L5–S1 Herniation | |

Posterolateral–S1 nerve root | Back of leg/calf/bottom of foot symptoms |

Far lateral–L5 nerve root | Back of leg/dorsum of foot symptoms |

The physical examination includes an objective evaluation of ambulation, spinal range of motion, and neural tension signs. The straight leg raising test is used to stretch the roots giving rise to the sciatic nerve, while hip and knee flexion are used to assess the roots giving rise to the femoral nerve. A complete lower-extremity neurologic examination, including motor, sensory, and reflex testing, is mandatory. In cases with suspected cauda equina syndrome (large disk herniation producing bilateral leg symptoms, saddle anesthesia, and bowel/bladder changes), perianal sensation and rectal tone must be evaluated.

Spinal Imaging

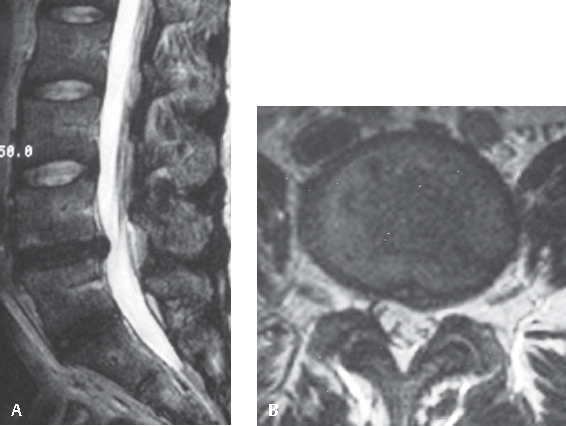

In the acute stage, radiographs are not required unless trauma, infection, or tumor is suspected. If the symptoms persist after 4 to 6 weeks of conservative care, plain radiographs should be obtained and an advanced imaging test such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) myelogram should be completed. MRI is the most useful imaging modality because it will generally demonstrate the etiology of neurologic irritation and is noninvasive (Fig. 29.1A,B). CT myelography is invasive but useful in patients with pacemakers or other contraindications to MRI, as it provides reasonably good imaging of the neural elements.

Treatment

Treatment

The treatment for lumbar radiculopathy is outlined in the algorithm. In the acute phase, an attempt should be made to limit the symptoms using activity modification, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), spinal injections, and oral analgesics. Limited evidence exists to support bracing in patients with lumbar radiculopathy. Physical medicine techniques (traction, acupuncture, massage, transcutaneous electrical stimulation, and biofeedback) may benefit some patients but have not been proven in recent literature. When the symptoms persist for a prolonged period (> 6 weeks) and fail to respond to conservative measures, surgical intervention should be considered.

Fig. 29.1 (A) T2-weighted sagittal MRI of an L4–L5 herniated disk. (B) T2-weighted axial MRI of a lumbar herniated disk.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree