Long-Term Results of Total Hip Arthroplasty

William N. Capello and James A. D’Antonio

Key Points

• Cement fixation of the femoral component remains a viable option in primary hip replacement.

• Stable initial fixation is a common requirement of all cementless component fixations.

Introduction

Total hip arthroplasty over the past five decades has evolved to become a remarkable reconstructive procedure that relieves pain, restores function, and returns patients to independent activities of daily living. This chapter will discuss the long-term results of primary total hip replacement, both cemented and cementless. We have elected to discuss acetabular and femoral component results separately, and we have included a discussion of bearings and their influence on long-term fixation. When possible, articles quoted will have at least a 10-year follow-up.

Femoral Components in Primary Total Hip Replacement

Femoral component fixation, once the major reason for revision in primary total hips, has improved to the point where we can expect the component to survive for decades. Advances in prosthetic design, implant finishes, instrumentation, and cementing technique have led to improved fixation of both cementless and cemented femoral components.

Cemented Fixation

Since Sir John Charnley popularized the use of polymethylmethacrylate as a fixative for femoral implants, the use of cement and the results of that form of fixation have served as the standard by which all other methods of fixation have been gauged. The Norwegian Arthroplasty Register for the year 2007 shows that more than 70% of primary total hips done that year had cemented femoral fixation.1 However, if one separates out those patients who are younger than 60, the same registry for the same year shows only 35% of patients in that subset having cement fixation. Without a registry, it is difficult to determine accurately the usage of cement in femoral fixation in the United States; however, it appears that cementless fixation is becoming increasingly popular among U.S. surgeons. Long-term studies of cemented components show excellent durability. Lewthwaite and colleagues from Exeter in a challenging group of patients 50 years of age and younger followed for 10 to 17 years reported no femoral component revisions due to aseptic loosening over that time interval.2 Buckwalter, Callaghan, and others in Iowa looked at the Charnley hip at a minimum of 25 years of follow-up and found some deterioration as the result of fixation over time; even at 25 years, 90% of femoral components in those patients still alive remained in place and were functioning well. A similar paper by the same group from Iowa looked at 25-year results of patients younger than 50 at the time of their index surgery; this was a follow-up of a previous report of a 20-year follow-up.3 Over that intervening time interval, no deterioration of fixation of the femoral component was noted.

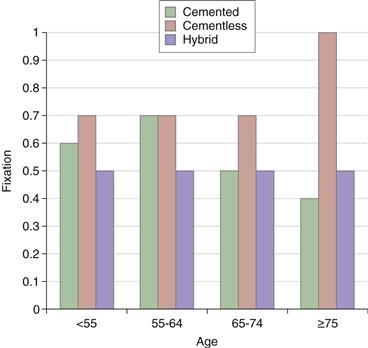

The Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry looks at survivorship in the form of revision per 100 observed component-years. Figure 60-1 shows that the durability of cemented stems, whether with cemented sockets or in hybrid form, is fairly consistent over various age groups; in fact, better survival than their cementless counterparts is evident at each interval presented.4 Over the past 20 years, improvements in prosthetic design, a better understanding of surface finish as it relates to implant survival, and better cement handling techniques have contributed to improve the durability of cemented femoral components.

Figure 60-1 Primary conventional total hip replacements requiring revision by fixation and age. (Data from the Australian Orthopaedic Association: National Joint Replacement Registry, 2007.)

In our own experience, two studies have looked at cemented femoral components.5,6 One group of 131 cemented total hips, followed between 5 and 12 years, underwent revision for aseptic loosening at 2.3%. An additional patient was noted radiographically at 11-year follow-up to have a loose stem, yielding a total mechanical failure rate of 3.1% for cemented stems. The second study, which focused on hybrid hips with an average of 9 years of follow-up (range, 5 to 12 years), involved 102 hips and had a mechanical failure rate of 2%. In both instances, the canal had been vigorously reamed at the time of the index total hip. In both series, a second-generation cement technique was used; this consisted of plugging of the canal, brushing, cleaning of the canal, retrograde loading with a cement gun, and proximal pressurization. At that time, no attempt was made to reduce cement porosity through centrifugation or vacuum mixing. In both studies, we were able to achieve femoral component fixation of 97% out to 11 years of follow-up.

Cementless Fixation

This section will describe cementless fixation of femoral components as it relates only to total hip arthroplasty. It will not include hemiarthroplasties or press-fit arthroplasties that are never expected to achieve biological fixation. Over the past 15 years, a variety of means of securing the femoral component in a cementless fashion have evolved. All share one common characteristic, that is, the need for stable initial fixation followed by biological fixation in the form of bone ingrowth or ongrowth onto the prosthetic surface. Various surface treatments have been shown to be very effective in establishing the long-term durability of cementless femoral components. These include porous coated surfaces—both those confined to the proximal part of the implant and those extensively covering the implant. Roughened surfaces such as arc deposit or plasma spray applications, and in some cases simply roughing the titanium substrate through grit blasting, have provided an excellent milieu for bone ongrowth. In addition, ceramic coatings such as hydroxylapatite have been applied to finely roughen substrates of titanium or grossly roughened surfaces and have proved successful.

Two basic stem designs have evolved over the years for use in primary hip replacement. One is the use of diaphyseal fixation with a cylindrical stem that is slightly oversized to the preparation and achieves excellent interference when press-fit through this mechanism. The best example of this type of fixation is the anatomic medullary locking (AML) prosthesis. Engh and coworkers,7 who popularized the use of this implant, followed a series of patients for a minimum of 10 years. The average age of patients in that group at the time of surgery was 55 years. Among 174 patients remaining from that group, only 3 were noted to have clinical aseptic loosening. An additional 2 stems were judged to be radiographically loose but were unrevised over the same period. All of these 5 stems were judged to be undersized at the time of initial implantation.

A second type of stem is a proximally fixed implant. Almost all of these have a wedge shape with taper built into them. A number of articles have reported excellent results with these implants. Lombardi and associates looked at 191 Mallory-Head implants (Biomet, Warsaw, Ind) followed for 14.5 years. Of these 191 implants, 61 had an additional hydroxylapatite coating over the plasma spray. The remaining 131 did not contain hydroxylapatite, only plasma spray. At follow-up, survivorship of those stems with just the plasma spray was 99.2%, and of those with hydroxylapatite plus the plasma spray, 100%.7 Archibeck and colleagues, using a proximally fitted implant with fiber mesh placed circumferentially, had excellent results in a young group of patients followed a minimum of 9 years. Thus far, no femoral revisions have been reported in this group, and none were radiographically loose.8 Teloken reported on a cobalt chrome proximally fixed implant, the TriLock (Medartis, Basel, Switzerland), with 10 to 15 years of follow-up. No femoral loosenings were noted, and two components showed evidence of radiographic instability. This was out of a total of 49 hips followed during that time.9

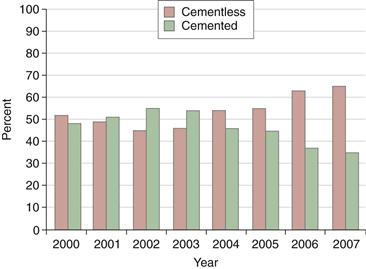

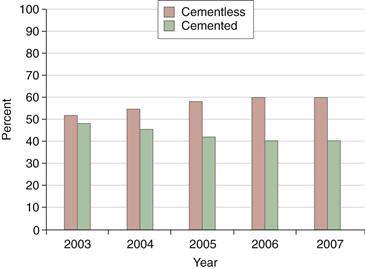

Cementless femoral fixation seems to be the most popular choice among surgeons for patients who are relatively young. Even the Norwegian Registry for the year 2007 showed that among this subset of patients, more than 60% received cementless component fixation (Fig. 60-2). The Australian Registry shows that 60% of all patients undergoing primary total hips received cementless femoral fixation in the year 2007 (Fig. 60-3).

Figure 60-2 Cementless femoral components in patients younger than 60 years. (Data from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Registry, 2007.)

Figure 60-3 Percentage of femoral components used in primary conventional total hip replacements, 2003 to 2007. (Data from the Australian Orthopaedic Association: National Joint Replacement Registry, 2007.)

Our own experience with hydroxylapatite-coated stems spans 21 years (Table 60-1). This prospective study began in 1987 and involves patients from four centers. The implant has a tapered, double-wedged configuration made of titanium alloy; it has a roughened surface attained through grit blasting, and a 50-micron layer of hydroxylapatite has been plasma sprayed to the upper third of the implant. The average age of patients at the time of implantation was 51.8 years, half are males, and 67% carried the diagnosis of osteoarthritis. At 21 years, 94.43% of the stems remain in place, and survivorship with aseptic loosening as the end point is 99.5%. Only one has been revised for aseptic loosening. This stem has shown remarkable durability in this young group of patients followed now for two decades. We have also documented the remodeling changes that occurred around this implant.10 It appears that remodeling changes continue for many years post implantation. We have noted that even between 15 and 20 years of follow-up, fairly significant changes occurred. A second study, involving the same stem, is also prospective and multicentered but has a control group relative to the bearing surface. This study involved ceramic-on-ceramic bearings compared with a metal and polyethylene bearing. Of a total of 475 hips, 65.5% were male, and average age at the time of surgery was 53 years. Four stems (0.84%) have been revised since the study began, none for aseptic loosening. By combining these two studies, we have 737 patients followed between 13 and 21 years with only one known case of aseptic loosening that occurred at 9.5 years post implantation.

Table 60-1

Stem Survivorship of Omnifit Hydroxylapatite (HA) (N = 262)

| Survivorship | HA Stem Revision for Any Reason (N = 262) | HA Stem Revision Due to Aseptic Failure (N = 262) |

| 1 year | 99.24% | 100% |

| 2 years | 98.84% | 100% |

| 3 years | 98.84% | 100% |

| 4 years | 98.94% | 100% |

| 5 years | 98.44% | 100% |

| 6 years | 98.03% | 100% |

| 7 years | 97.62% | 100% |

| 8 years | 97.21% | 100% |

| 9 years | 97.21% | 100% |

| 10 years | 96.79% | 100% |

| 11 years | 95.92% | 99.55% |

| 12 years | 95.47% | 99.55% |

| 13 years | 95.01% | 99.55% |

| 14 years | 95.01% | 99.55% |

| 15 years | 95.01% | 99.55% |

| 16 years | 94.43% | 99.55% |

| 17 years | 94.43% | 99.55% |

| 18 years | 94.43% | 99.55% |

| 19 years | 94.43% | 99.55% |

| 20 years | 94.43% | 99.55% |

| 21 years | 94.43% | 99.55% |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree