Lateral Positioning

Joseph C. McCarthy

Maureen K. Dwyer

The lateral approach requires the patient be placed in the lateral decubitus position with the affected side up. Adequate padding is critical to preventing pressure and neuropraxias. An axillary roll is placed under the arm on the lower side. In addition, padding is placed under the leg on the lower side, specifically protecting the fibula head. The surgeon can stand either anterior or posterior to the patient, whereas the video monitor, image intensifier screen, and fluid pump equipment are placed opposite the surgeon for ease of viewing. Adequate visualization and access to the recesses of the acetabulum require distraction of the femoral head from the acetabulum.

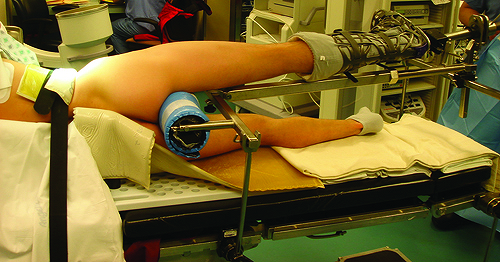

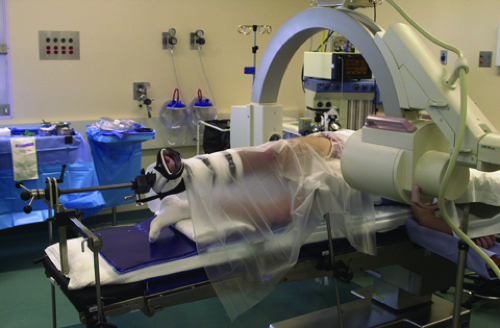

A fracture table or a specialized lateral hip distractor can be used with a standard operating room table. The foot and ankle are then carefully padded and the traction device is applied to the affected leg. Before applying traction, the hip is positioned in slight abduction, flexion, and external rotation to relax the capsule. The axial traction is applied first with the leg abducted between 0 and 20 degrees depending on the neck–shaft angle and the depth of the acetabulum. The hip is then placed in slight flexion between 10 and 20 degrees to relax the anterior hip capsule, facilitating the distraction. The foot is neutral or slightly externally rotated (1). A well-padded perineal post is placed 10 to 15 cm distal to the ischial tuberosity against the medial thigh. The placement is critical as it protects the pudendal nerve, preventing neuropraxia and also acts as a cantilever to lift the femoral head when traction is applied (Fig. 24.1) (1). The actual force required to distract the femoral head from the acetabulum varies considerably from individual to individual, but it averages around 25 lb (2). A fluoroscopic image intensifier is used in the AP plane to determine the relative distraction of the femoral head from the acetabulum. The fluoroscope can be positioned either above or below the table for adequate imaging. A tensiometer can also be used to monitor the distraction force. Seven to ten millimeters of distraction is required to facilitate safe entry of the arthroscopic cannulas into the joint.

Instrumentation designed specifically for the hip is required to facilitate insertion and maintain the position within the hip joint. Initial insertion of long spinal needles release the negative pressure vacuum created with distraction and can be confirmed with an image intensifier before portal placement. All arthroscopic instrumentation should be passed through metal cannulas long enough to protect soft tissues and neurovascular structures surrounding the hip and prevent loss of capsular distention.

The deep bony landmarks are the neck and head of the femur and the acetabulum. These are palpated with the spinal needle and the trochar as the joint is approached. The instruments pass through the gluteus medius and minimus muscles as they are directed into the hip joint. A definite “give” on either side is felt as the capsule is pierced, and the bony floor of the acetabulum stops the instrument. If bone is struck before the capsule appears to be penetrated, the instrument is placed too superior, striking the outer wall of the acetabulum, or too inferior, hitting the head of the femur. The vital adjacent structures to be avoided include

the sciatic nerve posteriorly and the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve anteriorly. The femoral artery and nerve anteriorly and the superior gluteal nerve are far removed from the portals of entry (3), but their location should be kept in mind.

the sciatic nerve posteriorly and the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve anteriorly. The femoral artery and nerve anteriorly and the superior gluteal nerve are far removed from the portals of entry (3), but their location should be kept in mind.

One of the advantages to this position is the familiarity of the anatomy for most hip surgeons. The greater trochanter and the anterior superior iliac spine are the landmarks utilized for this approach. The greater trochanter serves as the reference for each of the peritrochanteric portals. The anterior peritrochanteric portal is placed at the junction of the anterior and mid-1/3 of the superior ridge of the greater trochanter. This portal allows visualization of the femoral head, the anterior neck, and the anterior intrinsic capsular folds. The synovial tissues beneath the zona orbicularis and the anterior labrum can be easily seen and addressed from this portal as well (4).

The posterior peritrochanteric portal corresponds directly with the anterior peritrochanteric portal. The entry site is at the junction of the posterior and mid-1/3 of the trochanteric ridge at the level of the anterior peritrochanteric portal. The trocar is advanced with the femur in a neutral position to avoid injury to the sciatic nerve. This portal views the posterior aspect of the femoral head, the posterior labrum, posterior capsule, the ligament of Weitbrecht, and the inferior edge of the ischiofemoral ligament (4).

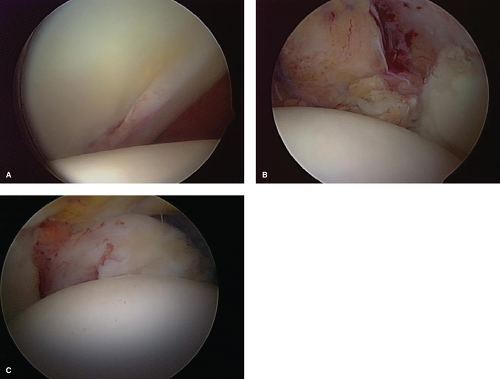

There are several advantages to using the lateral approach for arthroscopic surgery of the hip joint. The lateral decubitus position allows superior access to the joint along the superior, anterior, or posterior femoral neck through peritrochanteric portals compared with the supine position. However, access to the most inferior portion of the acetabular fossa for removal of loose bodies in conditions such as synovial chondromatosis is limited. There are fewer structures to traverse via the hip abductors. In obese patients, the lateral position provides improved maneuverability, as the subcutaneous abdominal and buttock fat falls away making entry easier. The joint capsule is thinner, allowing easier entry into the hip joint. There is less risk to the neurovascular structures, in particular the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (5). The anterior aspect of the joint where the majority of intra-articular lesions occur is well visualized with the portals (6), and there is less risk of iatrogenic injury to the labrum because in patients who have even mild dysplasia, the lateral labrum is thinner whereas the anterior labrum is enlarged and more likely to be damaged by an anterior capsular portal (Fig. 24.2) (7). Last, for patients with a cosmetic concern, the portal scars are less visible and less prone to keloid formation.

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|