NORTH AMERICA: UNITED STATES AND CANADA

Globally, the field of physical medicine and rehabilitation (PMR) is committed to providing quality, compassionate, holistic, and team-oriented care to people with disabilities. Rehabilitation practitioners worldwide work to improve quality of life and enhance functional status through a combination of team work, dedication, and focused assessment of a patient’s functional strengths and deficits within a medical and psychosocial context (

3). American physiatrists have a long history of involvement in international PMR activity (

4). The process of rehabilitation has been compared to “performing surgery from the skin out” (

5) in that significant realignment, readjustment, and modification of a patient’s environment and circumstances must be performed in order to compensate for impairments and functional deficits.

Within the context of international aspects of RM, this section focuses exclusively on the North American experience. It provides a concise overview of salient topics including a brief history of PMR focused on the development and evolution of the specialty in the United States, an analysis of the major practice areas and specializations among US physiatrists, demographics, consideration of cooperative and harmonizing projects, review of US residency training and educational matters, discussion of problems and recent challenges, elaboration on international outreach efforts such as exchange programming, discussion of the Canadian system of rehabilitation, and a forecast for the future of rehabilitation in North America.

Due to the preeminent role that the United States and Canada have played as a beacon of education and enlightenment for international medical education, this chapter would not be complete without a description of the importance of international educational exchange programs in PMR. Under the auspices of the International Society of Physical Medicine

and Rehabilitation (ISPRM), the Faculty-Student Exchange Committee (www.isprm-edu.org) is composed of international members. It is presently directed by a United States-based elected physiatric leadership and has been responsible for the building of global educational and humanitarian bridges in physiatry. This topic is elaborated upon later in this chapter (page 542).

The field of PMR in North America traces its origins to the mid 20th century when a seismic shift in thinking among health care providers occurred. Due to the burgeoning numbers of wounded and injured soldiers emanating from the war, a new emphasis was placed on the value of comprehensive, team-oriented care for people with disabilities of all types. The critical importance of ministering to and caring for people with disabilities all across America soon came to be recognized as an essential societal and ethical obligation.

During the early days of PMR, the specialization was actually divided into two separate and distinct areas: physical medicine

and rehabilitation (

6). Frank Krusen (1898-1973), the author of the first rehabilitation textbook and the founder of the first residency training program in physical medicine (Mayo Clinic), is largely credited for his pioneering role in physical medicine which focused on the use of electricity, heat, light, mechanotherapy, exercise, and other modalities in the alleviation of disease and disability. To differentiate physical medicine physicians from physical therapists, Krusen originated the name “physiatrist”—an appellation that has stuck to this day.

Almost simultaneously, the legendary Dr. Howard Rusk (1901-1989), responding to the need for help with the medical and functional restoration of wounded, disabled soldiers returning from active duty, started the field of rehabilitation within the United States. Rusk’s early pioneering efforts resulted in the establishment of one of the first comprehensive inpatient rehabilitation hospitals—the Rusk Institute of Rehabilitation Medicine at New York University.

Within the United States, physical medicine was first (primordially) recognized as a medical specialty in 1947, with the establishment of the American Board of Physical Medicine. In 1949, the word “rehabilitation” was added to the name. Over the years, PMR as practiced in the United States has evolved steadily. During the 1980s and 1990s, inpatient rehabilitation remained the mainstay of physiatric practice. More recently, there has been an increased shift in emphasis toward outpatient services.

PMR has prospered as a medical specialization, not only in mainland United States, but also in its territories. In Puerto Rico, for example, physiatry has grown by leaps and bounds. Dr. Herman Flax, one of the early pioneers of PMR in Puerto Rico, chronicled the history and development of the field over a 25-year period (

7).

Within the United States and Canada, PMR is a medical specialty approved by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education that emphasizes prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of persons with disabilities who experience restrictions in function resulting from disease, injury, or symptom exacerbation. Practitioners of PMR are known as “physiatrists” and utilize a holistic and team-oriented treatment approach which often combines medication, injections, exercise, physical modalities, and education customized to the patient’s unique requirements (

6). PMR specialists offer care for persons with neuromuscular disorders who have acute and chronic disabilities. The overriding goal of PMR is to optimize patient function in all domains of life, including the medical, emotional, social, and vocational spheres.

With the “graying” and aging of the North American population, physiatry has grown significantly in its stature as a medical specialization and has been considered the “quality of life” medical specialization because of its unique focus on functional restoration and contribution to the conservative nonsurgical management of an aging population.

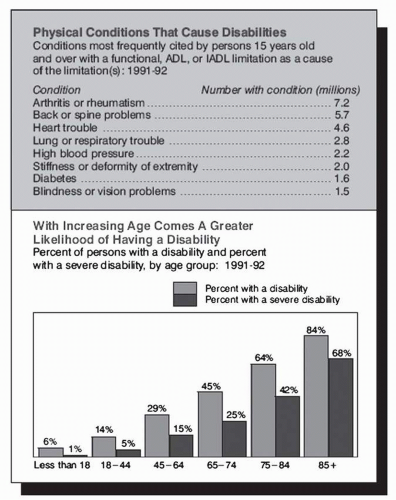

According to US Census 1990-2000 data, approximately 49 million noninstitutionalized Americans have a disability (one in five Americans). While there are many causes of disabilities, the most salient ones are those resulting in deficits of activities of daily living.

Figure 22-1 below describes the most common conditions known to cause disabilities along with their respective prevalence.

Physiatrists in the United States practice within diverse and varied work settings. Although their work activities and specializations vary widely, there is still much consistency in work distribution. According to a 2005 study commissioned by the American Academy of Physical medicine and Rehabilitation

(AAPM&R), a majority of American physiatrists (according to time allocation) are involved in the general practice of PMR in the outpatient setting (50.1%), inpatient venue (23.1%), administration (9.8%), academic activities (4.4%), and research (2.8%). An AAPM&R comprehensive membership survey study conducted in 2002 revealed that for all respondents: 56.6% described themselves as “private practitioners” and 44.2% as “employed.” Approximately 0.8% of the above were both in private practice and employed.

Regarding physiatry employment settings for “employed physiatrists,” 47.2% worked in a hospital or rehabilitation institution, 41.8% in an academic setting, 9.4% as VA employees, and 6.1% as HMO employees. Many of the “employed physiatrists” worked in multiple areas. Regarding private practice physiatrists, 44.3% were in solo practice, 29.9% were in multiple specialty, 29.7% in single specialty, and 2.9% in other practice settings.

The pathway to becoming a board certified physiatrist in the United States begins in medical school. After completing 4 years of medical school, the medical school graduate enters an internship which is a 1-year sequence of coordinated rotations emphasizing basic medical skills within a transitional environment or an accredited training program in internal medicine, surgery, pediatrics, family medicine, obstetrics and gynecology, or some combination thereof. The 1-year internship period is followed by a 3-year residency training program in PMR.

At the conclusion of the 3-year residency, the qualifying graduate takes a board exam administered by the American Board of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (ABPM&R). Once this exam is successfully completed, the graduate takes another exam, the oral board, at the conclusion of the first year of practice. Recertification is required of each graduate every 10 years.

An increasing number of PMR residency graduates are choosing to pursue accredited fellowship training in PMR subspecializations by the ABPM&R including Spinal Cord Injury (SCI) (2002), Pediatrics (2002), Pain Medicine (2002), Neuromuscular Medicine (2006), Hospice and Palliative Care (2006), and Sports Medicine (2006). Other nonaccredited fellowships exist in many areas. The typical duration of these fellowships is between 1 and 3 years.

The ABPM&R has published residency training statistics that focuses on demographics, program size, and composition, as outlined in

Table 22-1 (

8).

Two key textbooks frequently utilized by physiatrists throughout North America (and the world, for that matter) are

Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation: Principles and Practice by Joel DeLisa (

9) and

Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Medicine by Randall Braddom (

10). Other useful books include

Essentials of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation by Walter Frontera et al. (

11). Useful handbooks for medical students and residents include

PMR Secrets by Bryan O’Young et al. (

12) and

PMR Pocketpedia by Howard Choi et al. (

13).

The two main American journals of the PMR field are Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation and American Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. Starting January 2009, the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation started publishing a journal entitled: PMR, The Journal of Injury, Function and Rehabilitation.

While the field as a whole continues to carry on its noble mission of providing quality, compassionate care for people with disabilities of all types, the specialization faces a major challenge from some insurers and third-party payers who have steadily decreased reimbursement. In addition, shrinkage of the allotted lengths of stay for a growing number of diagnostic categories has taken place. An illustrative example of this is that of an acute stroke patient who is allotted on average approximately 14 to 21 days of acute hospital rehabilitation prior to community discharge. Unlike many parts of the world, where such patients would be treated for 2 to 3 months, the US system of care offers much shorter lengths of stay.

Another major change and challenge has been the advent of prospective payment systems (

14) for acute care hospitalization which has led to a shifting of patient care from the acute rehabilitation setting where rehabilitation is delivered in a focused concentrated fashion for approximately 3 hours a day to a subacute environment where the rehabilitation is less intense and often is of a “nursing home style” vintage. Throughout the United States, in order to promote vertical integration of health delivery systems, hospitals have transformed acute care beds into subacute care beds. In addition, many hospitals have purchased subacute care facilities including nursing homes and convalescence centers which serve a “surrogate rehabilitation” role.

Apart from the academic or hospital-based physiatric programs, an increasing number of private practice physiatrists (both solo practice and group practice) have now elected to focus a significant portion of their practice on pain management. This has occurred because of economic factors and arguably may pose a major threat to the roots and traditions of the field, since there may now be an evolving and diminishing number of available physiatrists to care for people with traditional disabilities such as stroke, SCI, and brain injury.

Within the educational and residency training realm, a growing and unprecedented number of graduating residents are pursuing fellowship training in PMR and a disproportionate number are choosing a pain management trajectory. Although some are restricting their practice to pain management, many still recognize the importance of remaining diversified and being prepared to care for persons with all types of disabilities. Since people with traditional disabilities (e.g., stroke, SCI, and Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI)) occupy an essential and ever growing portion of the health care bandwidth in the United States, rehabilitation “generalists” are very much in demand. A physiatrist’s higher calling of transcendent care and impassioned advocacy for persons with disabilities was recently noted in an issue of JAMA.

“As practitioners of the healing art, we are often swept away by the mundane minutiae of providing expert technical care to our patients. Often overlooked (however) is the human side of caring—that transcendent sense of seeing life through the eyes of our patients” (

15).

The field of PMR continues to thrive and prosper within the United States because of the synergy that it has engendered with other medical specialties and related rehabilitation disciplines. Since rehabilitation is recognized as a team effort, major bridges have been built with rehabilitation professionals across the spectrum including physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech and language pathology, recreational therapy, psychology, as well as rehabilitation nursing. More institutional and academic departments have integrated programs creating a fertile milieu for crossdisciplinary and transdisciplinary integration.

Above and beyond the clinical service delivery domain, physiatrists have teamed up with physical therapists, occupational therapists, speech-language pathologists, and other medical specializations including podiatry to carry out meaningful and impactful humanitarian objectives. A recent noted example of this is Operation Functional Recovery (OFR) which was an international project spearheaded by the ISPRM Exchange Committees (www.isprm-edu.org) aimed at helping hurricane Katrina survivors. OFR also rendered assistance in other worldwide rehabilitation cataclysmic events including the tsunamis, earthquakes, and other natural catastrophes (http://www.isprm-edu.org/human.html).

Operation Functional Recovery: The Rehabilitation Community’s Humanitarian Response to Hurricane was in part the subject of a recent AAPM&R Focus Session (

16).

On a worldwide front, the United States has taken the lead in organizing globalization initiatives in the domains of research, education, and humanitarian projects. Global initiatives in PMR present challenges for practitioners, yet offer many opportunities (

17). A detailed discussion of international exchange activity in PMR appears in a later chapter in this text book.

Much like its Southern neighbor, Canada prides itself in providing quality, focused, functional-based care for citizens with disabilities. In Canada, after the completion of medical school (typically 4 years), physicians enter residency training through the Canadian Resident Matching Service. In 2008, there were 25 PMR positions available throughout the country, offered in 13 different institutions in the following provinces: Alberta, British Columbia, Manitoba, Nova Scotia, Ontario, Quebec, and Saskatchewan (

18).

The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada (RCPSC) accredits the postgraduate education programs for physiatrists. The program consists of 5 years of specialty education. During the first year, residents complete their basic clinical training. This consists of several off-service rotations, including internal medicine, surgery, as well as additional 1-month electives. This is then followed by 4 years of training in both physiatry and additional rotations which are pertinent to physiatry (neurology, orthopedics, rheumatology, etc.). During their final year, residents complete the Royal College certification examination. This consists of both a written component and an Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE). In contrast to the United States, both components of the examination are completed in the residents’ final year. Following successful completion of this examination, the physician is awarded the designation: Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada.

Most physiatry residents also choose to complete 6 months of neuromuscular disease/electromyography training during their residency. This allows them to sit for the Canadian Society of Clinical Neurophysiologists electromyography examination which is administered to both physiatry and neurology residents.

Canada, with a population of 33 million (

19), currently has 373 physiatrists (

20). As Royal College certified specialists, all physiatrists must participate in the RCPSC Maintenance of Certification program and must accumulate 400 hours of continuous medical education (CME) credits over a 5-year cycle.

The Canadian Association of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (CAPM&R, capmr.medical.org) is the national organization for physiatrists in Canada. Its main goals are to promote education, scientific collaboration, and practice development among physiatrists. A 2006 survey by the CAPM&R indicated that 53% of physiatrists are in private practice. Of those, one third do not carry inpatients. Seventy-eight percent of physiatrists have clinical or academic university appointments. Similar to the United States, there has been a shift in the practice patterns of physiatrists to an outpatient focus. The inpatient system is moving toward a model where hospitalists/family physicians are the attending physicians of record, and physiatrists act as the consultant.

In contrast to the United States, where health care is more managed care driven, Canada has a universal health care system. In this model, every citizen has equal access to health care and is fully insured by the government for all medically necessary care. This has both advantages as well as drawbacks with respect to the inpatient system. It ensures that anyone who benefits from rehabilitation services will be given the opportunity to participate in a program. Another advantage is that inpatient length of stay varies depending on the needs of the patient, and this is decided by the physiatrist and the rehabilitation team. For example, in the stroke population, the average length of stay in Canada is longer (40 days) (

21). By contrast, a drawback of Canada’s social system is that wait times can be prolonged compared to the United States; the time from onset of stroke to inpatient rehabilitation admission is an average of 29 days (median: 15 days).

In conclusion, the North American contribution to international rehabilitation has been immense. As outlined earlier in this chapter, the humble origins of the field of PMR began in the United States with the work of dedicated pioneering physicians including Dr. Howard Rusk and Dr. Frank Krusen. Over time, the specialization has grown considerably.

LATIN AMERICA

The origin of rehabilitation as a medical specialty in the developed countries and at the global level was linked to historical facts that promoted a great number of disabilities, such as the two World Wars in the first half of the last century. However, within Latin America the main impetus for the development of RM was the outburst of epidemics of transmissible illnesses

such as poliomyelitis, which is now eradicated in many of the region’s countries. This brought about an improvement in sanitary conditions and a rapid development of rehabilitation as a medical specialty. These phenomena emerged simultaneously in many Latin American countries.

European countries such as England, France, and Germany, as well as the United States, served as models for many of the Latin American rehabilitation systems. Initially, the area of expertise was predominantly focused on aspects of Physical Medicine, and later on, RM started to develop as well. A continuous demand for the improvement in sanitary conditions and the possibilities for the development of the rehabilitation field at the national level hastened the development of these therapeutic modalities in this part of the world.

Scientific Societies of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation were being established in the individual countries of Latin America and the Caribbean in the 40s and 50s, and consequently, the need of a Latin American Association that would bring these societies under one umbrella organization was recognized.

In 1961, during the first Mexican Congress of Rehabilitation, the distinguished Mexican Doctor, Alfonso Tohen Zamudio, brought together representatives from all Latin American countries. At that congress, they laid the basis of the Latin American Medical Association of Rehabilitation (AMLAR) and decided to hold the first AMLAR Congress in Mexico 2 years later in 1963, the second in 1967 in Peru, and the third in 1969 in Uruguay. Ever since that time, 23 congresses of the AMLAR took place. The AMLAR’s presidency is in Uruguay, since the XXIII Congress, held in the city of Punta del Este (Uruguay), in October of 2008.

Rehabilitation in Uruguay has its origins in the 1940s. Prof. Alvaro Ferrari Forcade saw that there was a need for a functional measurement tool to assess the patient’s status. He developed a scale that registers the patient’s functional clinical state in three basic categories: somatic, psychological, and social. The scale assigns a score to each of the categories, in such a way that the results depict the patient’s “profile of disability.” Moreover, it allows for predicting the patient’s functional outcomes (

22,

23).

In this way, the first functional measure of disability in Latin America was developed. Due to the fact that the implementation of this scale was done early in the development of RM in the region, its importance was not fully acknowledged at the time. This can explain the reason why this scale did not catch on while other such scales did, shortly afterward, in other parts of the world.

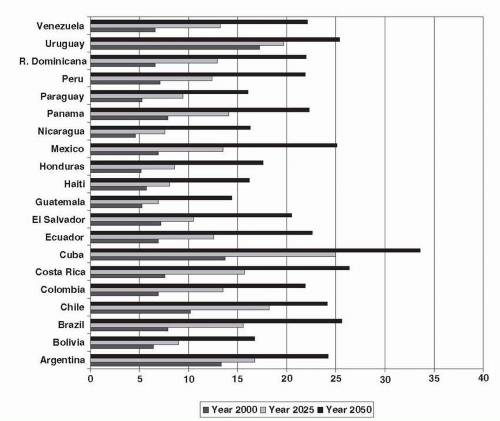

Latin America spans a large area with respect to political, geographic, demographic, and epidemiologic aspects. This is the reason for the varied degrees in the implementation of the RM and access to technology in the Latin American health systems. The demographic projections for Latin America and the Caribbean show that there will be progressive and dynamic changes during the course of next 40 years. These trends show a shift in the demographic profile, with significant aging of the population, due to a decrease in the birth rate and an increase in life expectancy for those over 60 years of age.

Even though in all the countries there is a marked increase in the population 60 years of age and above, the demographic change is not homogeneous and while some countries are still in an initial stage of increase, others are in a more advanced phase (

24). Cuba in the Caribbean and the countries of the south cone (Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay) in Latin America, have a more aged population (

Fig. 22-2), showing a more advanced transition.

This demographic change has a consequence from the epidemiological point of view. An increase in the elderly population will increase the prevalence of chronic nontransmissible illnesses related with the elderly. There is also an increase in the occurrence of nontransmissible illnesses linked to trauma and habits of life (accidents, social violence, accidents at work, and addiction) that coexist in the region with the transmissible illnesses. The increased number of high-risk newborns, along with malnutrition and the societal exclusion of indigenous ethnic groups (

25), all contribute to the increase in the demand for qualified RM practitioners. The growing demand for rehabilitation professionals, and that these professionals be trained to the highest standards and continue their training after certification with a CME program, are the main focuses of the Scientific Societies of Rehabilitation and Physical Medicine of each country and AMLAR (

26).

It is estimated that the population with disabilities in Latin America is close to 85 million people. Out of those, approximately 3 millions are in Central America (

25). Although we know about the social and economic impact of disabilities in Latin America, it becomes more difficult to plan accurate strategies due to the lack of trustworthy epidemiological data. The reported data vary and it is not certain that they describe the true epidemiological situation in many of the countries, and neither are they statistically comparable. This is a consequence of using different disability concepts and different methodologies for gathering the information. Some countries have included questions regarding disability in the population censuses. Others have carried out specific surveys for disability considering the articles corresponding to the ICF (International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health). Generally speaking, the censuses have shown a lower prevalence of disabilities than the surveys. The discrepancy in the results is also due to what is considered a disability. Is disability based on the impairment a mainly medical concept? Or is it based on the functioning, integration, and the individual’s participation with consideration to the patient’s interaction with the environment? (This definition is based on the ICF paper “Measuring Disability Prevalence”. Social Protection Discussion Paper. No. 0706. The World Bank. March 2007). This heterogeneity in concepts and methods makes the comparison of the results difficult when referring to the prevalence of disabilities in Latin America (

Table 22-2).

RM has developed in Latin American countries but not uniformly. The availability of rehabilitation facilities is found in 78% of the countries. There is specific legislation regarding rehabilitative medicine in 62% of the countries and implementation of specific programs in 51% of the countries. The field

is further hindered by very limited documentation of relevant data and limited research work. The practitioners are either specialists in rehabilitation or technicians consisting mainly of physical therapists, in addition to speech-pathologists, psychologists, nurses, social workers, and occupational therapists. The medical schools and colleges offer little training and teaching in the field of rehabilitation. In addition to the factors mentioned above, there are additional roadblocks to

the progress of RM in Latin America. Some of those problems are there are too few practitioners of RM in most countries; people with disabilities have a hard time integrating themselves into society; the private sector plays a preeminent role in the health care systems and is reluctant to pay for rehabilitative medicine (

25); large sections of the population do not have accessibility to medical aid, let alone to rehabilitation facilities. There is a distinct association among disability, poverty, and social exclusion.

On the whole, the number of specialists in RM is in fact greater than the one registered by each national scientific society.

Table 22-3 refers to the approximate numbers of physicians in some countries of the region, which have exceptionally low rates of specialists per inhabitants.

RM as a medical specialty was strengthened by unifying approaches to rehabilitative medicine which took place at the study group on The Training of Specialists, summoned by the PAHO/WHO in Santiago, Chile, in October 1969 (

23).

There are three basic models of rehabilitative care in Latin America: (a) hospitals of acute care, (b) rehabilitation centers, or (c) community-based rehabilitation (CBR). Most countries have an emphasis on one of these models and subsequently affect the specialist’s profile in each country. Uruguay is an example of a country that uses the rehabilitative model based on hospitals of acute care while promoting the interdisciplinary approach of the rehabilitation. They have recently started to work on rehabilitation centers related to pediatric care. Argentina and Chile have developed the models based on hospitals of acute care and rehabilitation centers. Nicaragua, El Salvador, Colombia, Argentina, and Guyana have developed the model based on CBR. Together with the help of nongovernmental organizations, the respective governments are developing this model in Mexico, Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia. Brazil is a remarkable example where all three models are used. The multidisciplinary diagnostic and therapeutic approach of disability treatment in Brazil has been an important factor in the development of rehabilitation in this country. The Rehabilitation Institute of the Hospital das Clinicas of Sao Paulo, the ABBR in Rio de Janeiro, and the Rehabilitation Institute of San Salvador were pivotal academic training sites in the specialty of rehabilitative medicine for Brazil and also for the region. In the early 70s, Brazil was one of the first countries that developed a residency program in rehabilitation training (

27). This residency program was used as a model for other such programs in others countries of the region.

The technology used in rehabilitation has improved from the 90s in several countries such as Argentina, Chile, Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico, especially in the field of orthopedic and neurological rehabilitation. Improvements in these countries had a positive effect throughout the region, in the practice of the specialty, in the academic training programs, and in the makeup of the specialist’s profile.

Recently, AMLAR has begun to work toward unifying the specialist doctor’s profile in the different countries of Latin America. They are trying to achieve this through the Societies of Rehabilitation and Physical Medicine of the individual countries, as well as in the specialist doctor’s CME, the professional certification, and certificate reexamination. In the XXI Congress of the AMLAR (Venezuela, 2004), it was agreed that specialists in rehabilitation should be qualified to perform the following: