Inflammatory Arthritis in the Child and Adolescent

Anthony A. Stans and Thomas G. Mason

Key Points

• Inflammatory arthritis (IA) in children frequently presents with more loss of function than pain.

• Isolated hip arthritis from IA is very rare.

• Many cases of IA in children and adolescents are not associated with serum autoantibodies.

• Nonsurgical therapies are the primary modalities to treat IA in children and adolescents.

• Surgical therapy for IA may be indicated if medical management has failed.

• Surgical synovectomy and osteotomy are rarely indicated.

• Bone-sparing technique should be used to facilitate later revision surgery.

Introduction

Inflammatory arthritis (IA) in children and adolescents represents a collection of medical conditions that may affect the axial and appendicular joints of the musculoskeletal system of children and teenagers. These conditions are not uncommon and can have substantial impact on functional status and quality of life. Hip involvement in these conditions is frequently associated with worse outcomes.1

IA in children and adolescents encompasses two diagnostic groups: juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA) and the spondyloarthropathies. Many pediatric rheumatologists prefer the term juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) to describe the IA of children and adolescents. Many similarities and some subtle differences in the definitions of JRA2 and JIA3 and their criteria and their subtypes are highlighted in Boxes 43-1 and 43-2. The primary difference between these definitions is the inclusion of many of the spondyloarthropathies in JIA. Uniting features of these conditions include age of onset and their chronic nature. For the purposes of this chapter, JRA terminology will be used, and the spondyloarthropathies will be discussed separately.

The term spondyloarthropathies (spondy) refers to a group of inflammatory conditions in which the spine and/or peripheral joints are affected in a characteristic pattern that is clinically different from JRA. Conditions that compose the group of spondy are listed in Box 43-3. Because the arthropathy of these conditions may be its initial manifestation, criteria for the early diagnosis of spondyloarthropathies have been developed and are shown in Box 43-4.4 Although the clinical definitions of psoriasis and forms of inflammatory bowel disease are beyond the scope of this chapter, criteria5 for the diagnosis of ankylosing spondylitis (AS) are shown in Box 43-5.

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

The incidence and prevalence of JRA vary with the population studied, but an incidence of about 1 new case per 10,000 children per year and a prevalence of about 1 in 1000 children were found in a population-based cohort.6 Of this cohort, about two thirds were pauciarticular onset, 10% were systemic onset, and the rest were polyarticular onset. Girls are more likely to develop JRA than boys, except for the systemic-onset subtype, which seems to have no apparent gender predilection. Studies from other centers show a higher prevalence of polyarticular-onset JRA, likely a reflection of the referral nature of those centers studied.

The epidemiology of spondy in children and adolescents is less straightforward, primarily because of lack of uniform terminology and precise definitions of these conditions. Anywhere from 1% to 20% of children seen at pediatric rheumatology centers may have spondy.7 The prevalence of ankylosing spondylitis (AS) ranged from around 70 to 210 cases per 100,000 adults, and AS has an incidence of between 7 and 9 cases per 100,000 person-years, depending on the population studied.8 Of patients diagnosed with AS, about 10% to 20% will be diagnosed before 17 years of age—juvenile ankylosing spondylitis (JAS)—although there are populations with higher juvenile prevalence in Mexico and Korea.9 Boys generally are more likely to develop spondyloarthropathies.

Genetic associations for JRA have been described but do not presently have prominent clinical applications. For spondy, however, the association with the class I HLA B-27 molecule is clinically important. The presence of B-27 is correlated with axial involvement in these conditions, and it may be found in almost 90% of teenagers with AS.10

Pathophysiology

JRA and spondy are chronic inflammatory conditions that affect the axial and appendicular musculoskeletal system. In general, these conditions are believed to be autoimmune, suggesting that established immune mechanisms somehow become “misguided” and initiate and propagate damage to these structures. This is an area of intense and evolving research. Components of innate immune system, adaptive immune system, cytokines, autoantibodies, and molecular genetics are examples of aspects of the immune system being studied for these conditions.

Of these areas, the association of spondy with HLA B-27 (see earlier) and the development of autoantibodies clearly have the greatest clinical relevance. Autoantibodies are antibodies that have affinity for self and are a hallmark of “autoimmune” conditions. Autoantibodies add prognostic information about forms of IA, but are not required for diagnosis of IA.

Although many types of autoantibodies are known, for children with IA, two are most useful for clinical management. The first of these is rheumatoid factor (RF). An RF is an antibody that has affinity to another antibody; several types of RF have been identified. Usually, serum RF is measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)—a sensitive, inexpensive technique. The presence of RF in the serum of children with polyarticular JRA increases the likelihood of damage and progressive disease, but most children with polyarticular JRA are RF(−).

The other important autoantibody in children with IA is antinuclear antibody (ANA). Similar to RF, most children with IA are ANA negative, but in children with pauciarticular JRA, the likelihood of uveitis is increased if ANA is found in the serum. Because knowledge of levels of these autoantibodies does not generally help in the longitudinal management of children who have IA, they are not generally sequentially assessed.

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

The key to diagnosing JRA and spondy in children is recognizing the patterns of clinical manifestations of these conditions. Criteria for JRA include at least 6 weeks of symptoms. Similarly, spondyloarthropathies are chronic conditions. Although acute joint inflammation could be associated with the initial presentation of one of these conditions, other causes of joint inflammation such as infection must be strongly considered in this setting. Septic arthritis is a medical emergency that cannot be overlooked. JRA and spondy are chronic, inflammatory conditions. Clinical features of inflammation are highlighted in Box 43-6.

The most common form of JRA, based on population studies, is pauciarticular JRA (pauciJRA). It is defined as arthritis in four or fewer joints, not associated with fever and other extra-articular features such as rash, adenopathy, and so forth2 (Box 43-7). Arthritis of JRA is defined as swelling or two of the following: joint tenderness, pain with range of motion (ROM), decreased ROM, or joint warmth in a diarthrodial joint.2

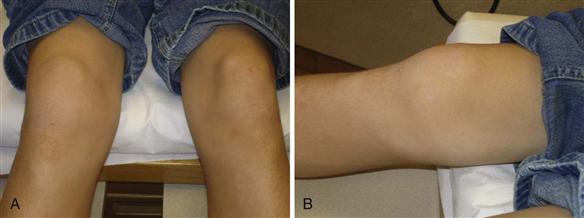

The “typical” case of pauciJRA presents in a preschool-aged girl with a painless limp and synovitis of a knee or ankle. Joint pain often is not the primary reason for evaluation of children with pauciJRA. Often, someone may notice that the child “walks funny” or seems to have a swollen joint, but that it does not seem particularly tender. This paradox may be contributed to by an insidious onset of disease, limited communication capacity of the child, the developing capacity for ambulation in this age group, or other factors. A knee effusion in a 10-year-old boy with pauciJRA is shown in Figure 43-1A and B. Most of these children do well, but a subset may develop involvement in other joints. Additional joint involvement in children with pauciJRA occurring more than 6 months after diagnosis is known as extended pauciarticular JRA. Estimates vary, but as many as one third of children with pauciJRA could become “extended,” with a higher likelihood in those with symmetrical and upper extremity presentation.11

Figure 43-1 A and B, This 11-year-old boy has an effusion in his right knee. Note the soft tissue enlargement medial to the patella along the medial joint line. He had diminished flexion but no pain with range of motion (ROM).

One of the most important features of pauciJRA is the increased incidence of uveitis, which is found in about 15% of patients.12 The development of uveitis is associated with the presence of ANA in the serum. The uveitis is usually asymptomatic but, if untreated, can have devastating visual consequences. It is mandatory for all children who have pauciJRA, especially if they are ANA positive, to undergo an ophthalmologic screening program for this potential complication. Girls who are diagnosed before the age of 7, and who have a positive ANA, are at highest risk and may need to be seen as often as every 3 months for screening.

Polyarticular JRA (polyJRA), defined as five or more joints with arthritis at the time of diagnosis, has many clinical features that are similar to those of rheumatoid arthritis in the adult. Similar to pauciJRA, polyJRA does not have fever as a major clinical feature. Frequently, symmetrical small joint synovitis with pain, loss of function, and morning stiffness is the pattern at presentation. Soft tissue swelling, restricted ROM, and small joint changes in a 13-year-old girl with polyJRA are shown in Figure 43-2A and B. Large joints, including the hips, may also be involved at the time of diagnosis, or they may become involved in the course of polyJRA. Subcutaneous nodules, typically over extensor surfaces, may be seen in some cases. Also, a few cases of polyJRA will have an associated RF in the serum. The presence of nodules and RF increases the likelihood of joint destruction and worse clinical outcomes.

Figure 43-2 A, Left wrist of a 13-year-old girl with chronic polyarticular juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA). Note the prominent synovial tissue on the dorsum of the wrist. B, Note decreased passive extension of the wrists and the boutonnière deformity of the right fifth finger in this same patient.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree