5 Improving Pain Management and Patient Outcomes Associated with Proximal Femur Fractures

Although improved pain management is an important aspect of patient care that profoundly influences patient outcomes, suboptimal pain management continues to be a prevalent issue in perioperative medicine. Surprisingly, this deficit in pain management has occurred despite the following advances in pain management: (1) improvement in medications; (2) improved analgesic delivery technologies; and (3) the development of pain management policies, protocols, and dedicated pain management teams (acute pain services) in primary and tertiary care hospitals. This discussion focuses on the impact of these important issues in the common setting of patients with acute hip fractures. For these patients, undertreatment of pain is associated with increased hospital length of stay, delayed ambulation, and long-term functional impairment.1

Pain, Acute Pain, and the Prevention of Chronic Pain

Chronic pain occurs when pain persists longer than the original acute pain was expected to last (commonly defined as >3 to 6 months). The cause is less identifiable and the pain less responsive to the usual peripheral nerve blocks or analgesics. Chronic pain exacts a huge toll in terms of morbidity and health care costs. The development of chronic pain often leads to the need for long-term care, which is the main cost burden in the health care system related to hip fractures.2

Multimodal Balanced Analgesia

Undertreatment of Pain

During Hospitalization

Pain continues to be prevalent among patients undergoing major surgical procedures. Data from 1973 to 1999 reported incidence rates of moderate to severe pain and severe pain of 29.7% and 10.9%, respectively.4 When only intramuscular (IM) analgesia was used, the incidence of pain was even higher: 67.2% and 29.1% for moderate to severe pain and severe pain, respectively. Moving forward to 2006, a cross-sectional study in a large Canadian teaching hospital showed that the incidences were essentially unchanged, at 31.5% and 11.4% for the same two categories.5 Postoperative pain levels vary for different surgical procedures, even among the surgical options for hip fracture repair. This finding should be taken into account in pain management.6

No evidence indicates that elderly patients experience less pain than younger patients.7,8 In patients undergoing hip replacement, no correlation was found between age and pain score.9 However, difficulties in assessment and concern about risk may lead to undertreatment of pain, especially in cognitively impaired elderly patients. In one study of hip fractures, patients with advanced dementia (median age, 88 years) received only one third the amount of opioid compared with cognitively intact patients (median age, 82 years), although 40% of the cognitively intact group already reported severe to very severe pain even with the higher opioid doses that they were given. Furthermore, only 24% of the noncommunicative patients received a standing order for analgesia.10 Thus, elderly patients are at high risk for undertreatment of pain associated with hip fractures.

After Hospital Discharge

Patients often report poor pain control following discharge from the hospital. Although it is known that a quick count of analgesics used in the 24 hours before discharge may provide an accurate indication of the analgesic requirement for the next few days, the potency, dose, and duration of analgesic prescribed often do not take into account differences in individual requirements. Moreover, after leaving the hospital, patients who had hip fractures were found to receive significantly less medication in the first 24 hours in the nursing home compared with the last 24 hours of hospitalization. More than one third of the patients received no opioid, and 18.3% received no analgesic of any kind.11 Communication about medical care should include treatment of pain and is essential for continuity of care as patients are transferred across settings.

Assessment of Pain

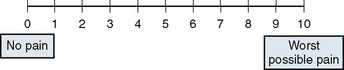

Unidimensional Tools

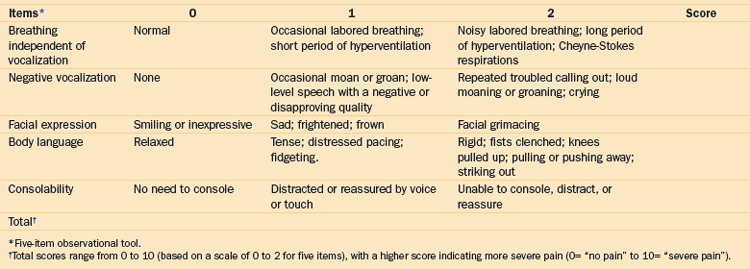

Observational (Behavioral) Tools in Elderly Patients with Cognitive Impairment

Elderly people find it more difficult to use self-report scales correctly than do younger adults.12 In some elderly and cognitively impaired patients, self-reporting may not be reliable. Changes in vital signs and autonomic responses as indicators of pain may be helpful in acute pain assessment, but these signs are nonspecific and difficult to discriminate from other states of distress. Observational (behavioral) tools have been developed to measure pain in cognitively impaired patients. These tools are staff administered and commonly estimate pain according to a checklist consisting of vocalizations, facial expressions, and body language that suggest pain (Table 5-1). Some tools were reported to have better reliability and validity (DS-DAT, PAINAD, PACSLAC, DOLOPLUS2, and ECPA),13,14 but no single tool is the most appropriate for use in elderly patients with cognitive impairment. Most observational tools need further vigorous development and testing.

Recommendations for pain assessment in elderly patients are as follows15:

Pharmacotherapy: Drugs Commonly Used in Multimodal Analgesia

Acetaminophen

Acetaminophen is thought to be a weak indirect inhibitor of cyclooxygenase (COX). It is an antipyretic and weak analgesic. It has few side effects unless the recommended dose limit (4 g/day in adults16) is exceeded. The United States Pharmacopoeia Dispensing Information (USPDI) recommends 2.6 g/day for long-term use (>10 days).17 There is no consistent age-related effect on the clearance of acetaminophen. Hence, one may not need to reduce the dose for elderly patients.18 However, in patients with preexisting liver disease or a history of heavy alcohol intake, daily doses should be reduced by 50% or 75%.18 Patients should be educated that many over-the-counter medications contain acetaminophen. Overdose may lead to fatal liver failure. In one report, acetaminophen was found to be the most common cause of acute liver failure, and it accounted for 39% of cases.19

Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs

NSAIDs have analgesic, anti-inflammatory, and antipyretic properties. These drugs can be used alone for mild to moderate pain. When used in combination with opioids, NSAIDs improve pain control and reduce opioid requirements by up to 30%.20,21 NSAIDs also decrease postoperative nausea and vomiting (≤30%) and sedation (≤29%).22

Cardiovascular Risk

In the VIGOR trial (Vioxx Gastrointestinal Outcomes Research), the relative risk of developing thrombotic cardiovascular event (myocardial infarction, unstable angina, cardiac thrombus, resuscitated cardiac arrest, sudden or unexplained death, ischemic stroke, and transient ischemic attack) with rofecoxib treatment compared with naproxen was 2.38. Further reports showing the cardiovascular risks of COX-2–selective inhibitors and other NSAIDs changed the recommendations about the use of NSAIDs in clinical practice.23–26

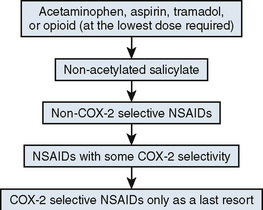

Published data showed an increased risk of cardiovascular event for COX-2–selective inhibitors (relative risk, 1.42) and some traditional NSAIDs. Individual drugs implicated included rofecoxib, diclofenac, meloxicam, indomethacin, high-dose ibuprofen (800 mg three times daily) but not lower-dose ibuprofen, piroxicam, naproxen, and celecoxib at 200 mg/day or less. In patients with previous myocardial infarction, selective COX-2 inhibitors in all dosages and nonselective NSAIDs in high dosages increased mortality rates.27–30 One review concluded that the overall risk of myocardial infarction with NSAIDs and COX-2–specific drugs was small, but rofecoxib had the highest risk.30 A Scientific Statement from American Heart Association recommended a stepped-care approach (Fig. 5-3) to management of musculoskeletal pain in patients with known cardiovascular disease or who are at risk for ischemic heart disease.31

Bone Healing

COX activity is involved in the healing of skeletal tissues. Indomethacin has been used to prevent heterotopic ossification after hip replacement. In some animal models, NSAIDs correlated with various degrees of bone healing impairment. There were also clinical reports that high doses or long-term postoperative use of NSAIDS increased the risk of developing fracture nonunion. However, a review of the literature showed contradictory results about the effect of NSAIDs on bone healing and a lack of well-conducted randomized clinical data.32,33 More research is required on this topic.

Gastrointestinal Complications

The incidence of hospitalization for NSAID-related upper GI bleeding is 1% to 2% per year, and this complication has a 5% to 10% mortality rate.34Helicobacter pylori infection and NSAID use act synergistically and are the two main causes of peptic ulcer.35 Factors in NSAID-related GI bleeding are age older than 60 years, a prior GI event, high NSAID dosage (>2 × normal), and concurrent use of corticosteroids and anticoagulants.36 Dyspepsia occurs in 10% to 20% of patients taking NSAIDs but is not predictive of ulcer development. In descending order, the highest-risk NSAID-related GI complications are caused by indomethacin, diclofenac, piroxicam, tenoxicam, ibuprofen, and meloxicam. Short-acting NSAIDs are less toxic than long-acting NSAIDs.37 The COX-2–selective inhibitor celecoxib is associated with an ulcer incidence similar to that seen with placebo.35 Most patients remain asymptomatic until they experience a life-threatening GI hemorrhage.

Taking NSAIDs with food can reduce GI side effects. The risk of NSAID-related ulcer is reduced by 40% with the use of misoprostol, a prostaglandin E analogue with side effects of nausea, diarrhea, and abdominal pain. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) have slightly lower efficacy but are better tolerated. Histamine (H2)-receptor antagonist therapy is inadequate.38

Optimization in Pain Control

Recommendations for the use of NSAIDs came from the Scientific Statement of American Heart Association,31 from reviewers,35 and from the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA). Recommendations from AGA Consensus Development Conference on the Use of NSAIDs include the following38:

Opioid Therapy

Underuse and Underdosing in Pain Control

Opioid drugs remain the definitive and highly effective therapeutic agents for most patients with severe pain. Many physician-related factors, patient-related factors, and legal and financial factors contribute to the underuse of opioids for pain.39,40 In patients with acute or postoperative pain, these factors include the following:

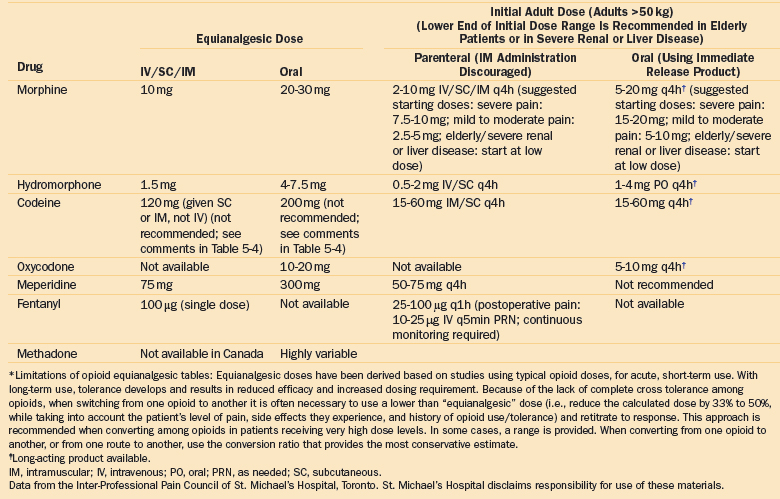

As with other medications, the analgesic effect of opioids is related to the plasma level of the drug. The mean effective concentration (MEC) and minimum effective analgesic concentration (MEAC) are used for assessing the relationship between opioid plasma level and effect. MEC is the concentration at the time remedication is required. MEAC is the steady-state concentration (determined by constant infusion) that produces analgesia. Although the MEC may vary four- to fivefold among patients,41 the doses prescribed are far too often much smaller than the recommended therapeutic doses needed to reach the MEAC. These patients are likely to have little to no pain relief rather than “partial” pain relief. At the same time, the prescribed doses do not always take into account the difference in relative potency among different opioid drugs, with the result that doses can be too low or too high.

A report from a large acute care hospital in 2006 showed that the median dose of morphine prescribed for surgical, medical, and emergency department patients was only 2 mg (interquartile range, 2 to 4 mg), and the lowest doses were given to surgical patients. In the same study, the doses of hydromorphone and meperidine prescribed were 6.7 times and 3.4 times more potent compared with the doses of morphine prescribed.42 These data suggest that although patients prescribed morphine are “underdosed,” those prescribed hydromorphone and meperidine receive a much more potent dose, possibly because of an incomplete understanding of medication dosing and potency (see Tables 5-3 and 5-4 for opioid equianalgesic conversion).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree