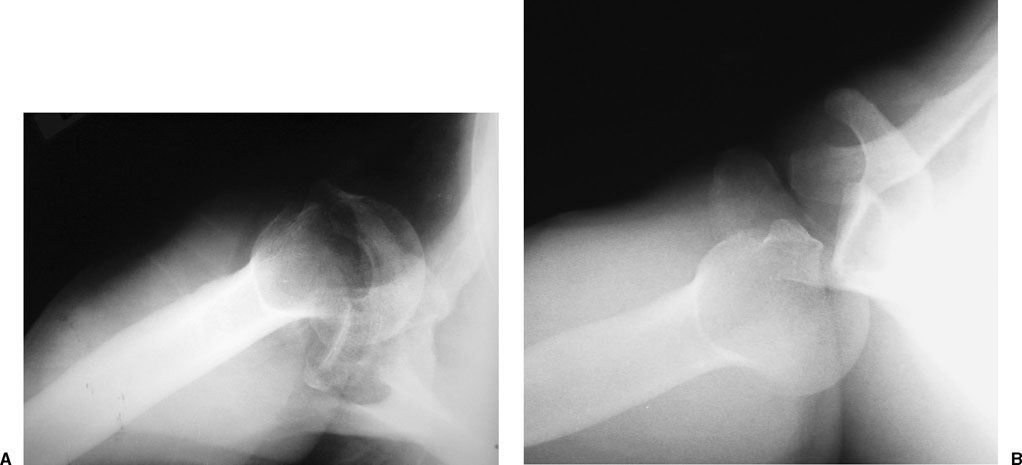

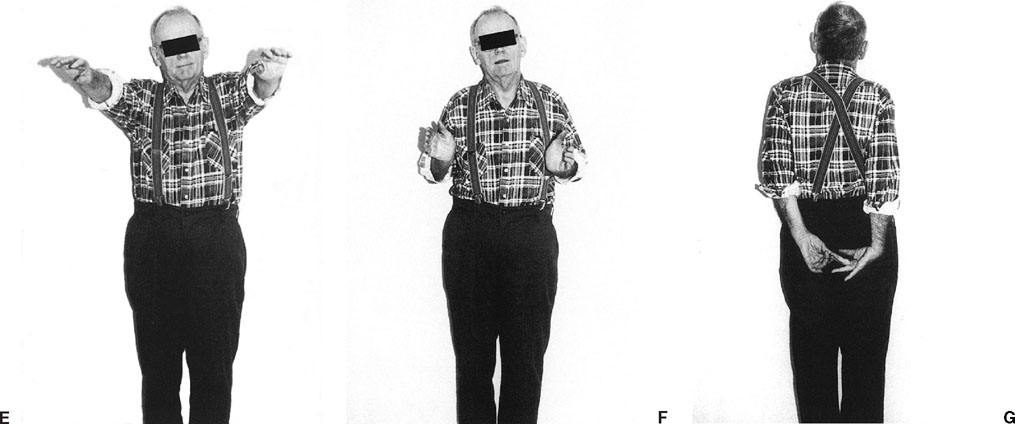

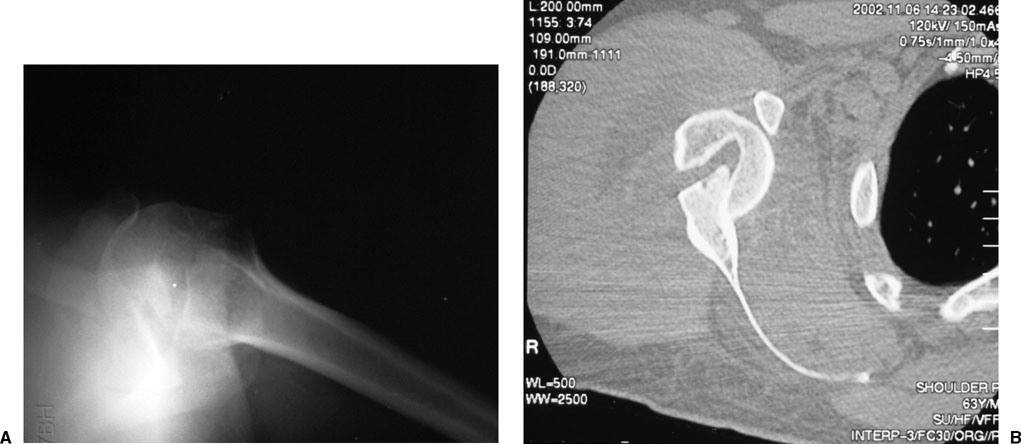

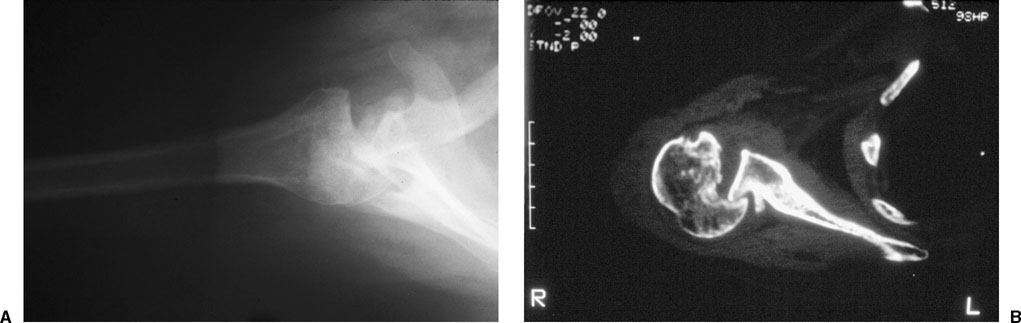

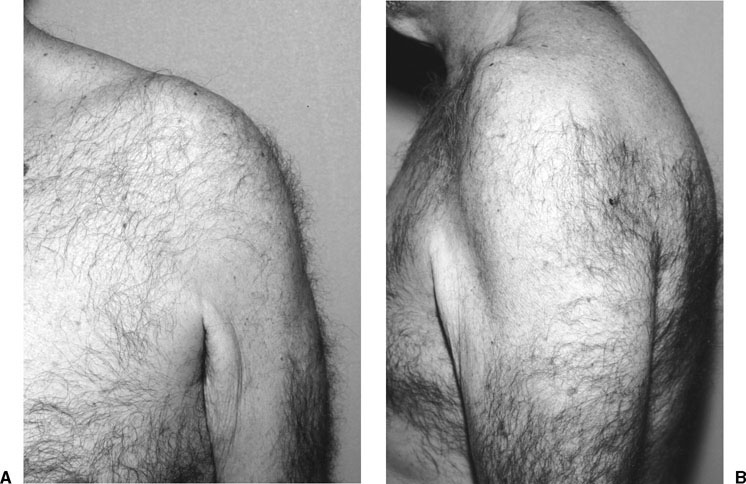

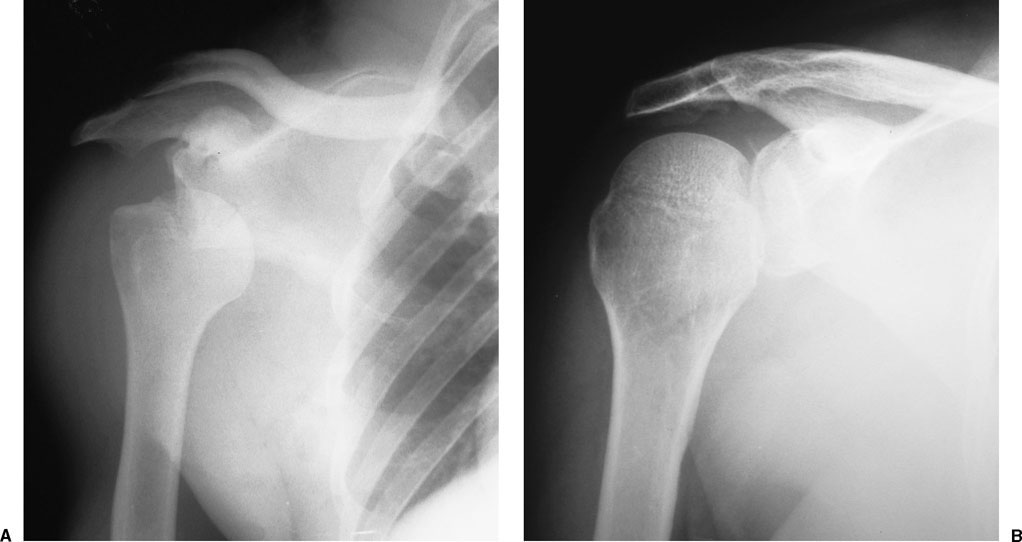

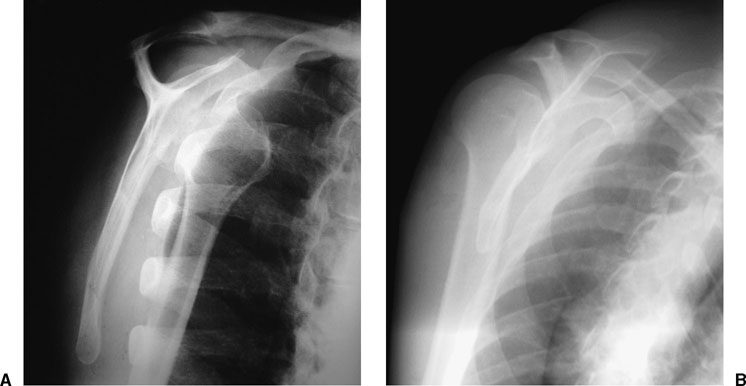

The diagnosis and treatment of impression fractures of the proximal humerus remain a challenge for the treating physician. The treatment of such lesions has been the subject of investigation for centuries, with reports of treatment of head impression fractures dating as early as 1741.1 The armamentarium of treatment options has since expanded, with successful management predicated on the recognition of these often challenging injuries, as well as a full understanding of the indications for specific approaches to treatment. Impression fractures of the proximal humerus occur with impaction of the humeral head against the glenoid rim at the time of shoulder dislocation. This can occur with an acute, first-time dislocation, but is more common with recurrent dislocations. The location of the humeral head impression fracture is dependent on the direction of glenohumeral dislocation. Anterior dislocations, which occur much more frequently than posterior dislocations,2,3 result in the classic Hill-Sachs impression fracture on the posterolateral aspect of the anteriorly dislocated humeral head as it impacts the anterior glenoid rim (Fig. 8-1).3,4 This defect has been observed in up to 100% of patients with recurrent anterior instability,5 80% with primary anterior dislocation,4,6 and 25% of patients with anterior shoulder subluxation.7 Although posterior dislocations account for only 1.5% of dislocations of the glenohumeral joint,2 they account for most chronic shoulder dislocations because of the significant number that are missed at the time of initial evaluation.3,8 Impaction of the anteromedial aspect of the posteriorly dislocated humeral head on the posterior glenoid rim results in the so-called reverse Hill-Sachs lesion (Fig. 8-2).9 This chapter addresses humeral head impression fractures that occur in association with chronic (dislocated for more than 3 weeks’ duration) shoulder dislocations. Patients presenting with impression fractures of the humeral head typically have sustained a chronic glenohumeral dislocation. These patients usually report a traumatic episode, such as a motor vehicle accident or fall from a height, a history of a seizure episode, or much less commonly an electrical shock. Because the internal rotators of the shoulder are inherently more powerful than the external rotators, seizures have classically been associated with posterior glenohumeral dislocations, although anterior dislocations have been reported to account for up to one half of all seizure-related shoulder dislocations.10,11 Multiply injured patients may sustain glenohumeral dislocations that are unrecognized due to other, more obvious or life-threatening injuries, or an inability to communicate their symptoms. Unrecognized glenohumeral dislocations are generally associated with substantial pain following the acute episode and limitation of shoulder motion that is typically attributed to pain inhibition. Patients with anteromedial humeral head defects associated with posterior glenohumeral dislocation typically complain of an inability to raise or externally rotate the arm. Patients with posterolateral impression fractures associated with chronic anterior dislocations may complain of a limitation of internal rotation; however, this is generally not as dramatic or consistent as the findings associated with posterior dislocation. With resolution of the shoulder discomfort—generally by 2 to 3 weeks after injury—the patient may initiate shoulder motion for activities of daily living (ADLs) at waist level; this resolution of pain and gradual functional return is often mistakenly attributed to recovery by the patient and treating physician, thus perpetuating the misconception that full functional recovery will occur. In reality, pain relief is due to resolution of inflammation from the initial injury as well as soft tissue healing, whereas the limited return of motion is secondary to the enlarging humeral head defect from the “windshield-wiper” effect of the glenoid rim within the impression fracture. FIGURE 8-1 Hill-Sachs impression fractures are located on the posterolateral aspect of the humeral head and can be visualized with different imaging techniques including an axillary radiograph (A) and a computed tomography (CT) scan (B). Alternatively, the patient with a chronic shoulder dislocation may report relief of pain following the traumatic episode, but with persistent limitation of motion. Such patients may be mistaken for having a posttraumatic frozen shoulder that fails to improve with efforts at rehabilitation.3,8,11 FIGURE 8-2 Reverse Hill-Sachs impression fractures are located on the anteromedial aspect of the humeral head as visualized on an axillary radiograph (A) and CT scan (B). A thorough neurovascular evaluation should be performed in patients with suspected impression fractures. Because many of the patients with impression fractures due to chronic glenohumeral dislocations are elderly, the relative incidence of neurovascular injury is higher than in younger patients who sustain acute dislocations. This may be due in part to the loss of elasticity and calcification of soft tissue structures that occurs with age. An association between nerve injury—in particular axillary nerve—and shoulder dislocation has previously been established, with up to 45% of patients with anterior shoulder dislocation and 29% of patients with posterior shoulder dislocation sustaining electromyographically demonstrable nerve injury.1,11,12 Similarly, injuries to the axillary artery in association with shoulder dislocations have been well documented.13–15 FIGURE 8-3 A 64-year-old man 1 month after posterior glenohumeral dislocation. Frontal view (A) shows loss of lateral contour of the shoulder, and side view (B) shows flattening anteriorly and fullness posteriorly. The patient with a posterolateral impression fracture due to chronic anterior glenohumeral dislocation may be surprisingly functional, with excellent functional capacity at waist level, minimal pain, and limited but functional range of shoulder motion. The shoulder is usually held in mild abduction and external rotation. Physical examination reveals squaring of the posterior acromion, loss of the lateral deltoid prominence, and anterior shoulder fullness, which are best observed with the patient seated and observed from behind or from the side. In thin patients, the humeral head may be palpable as a firm mass in the deltopectoral region. In heavier patients, these changes may be much less evident. Range of motion typically reveals limited adduction and internal rotation. Alternatively, the patient may present with severe functional limitations and restricted motion in all planes, similar in presentation to frozen shoulder. These patients are usually evaluated earlier in the course of chronic dislocation, potentially before significant enlargement of the humeral head defect has occurred from continued motion against the anterior glenoid rim. The patient with an anteromedial impression fracture due to chronic posterior glenohumeral dislocation tends to have a more characteristic presentation.16 By observing the seated patient from the front and side, the physician may appreciate subtle but consistent findings, including a loss of the anterior contour of the shoulder, prominence of the coracoid process due to posterior displacement of the humeral head, and a posterior fullness of the shoulder (Fig. 8-3). The arm is typically held in an internally rotated and adducted position, with loss of passive and active external rotation, and significant limitation of glenohumeral abduction. Long-standing chronic dislocation may also be associated with a surprisingly functional range of motion for activities at waist level. This is secondary to enlargement of the anteromedial humeral head defect by the “windshield-wiper” effect that occurs with shoulder motion. The shoulder trauma series consists of anteroposterior (AP), scapular lateral (“Y view”), and axillary projections. These three orthogonal views allow for the identification of surface defects or fractures of the humeral head, as well as the presence of glenohumeral dislocation. Chronic dislocations are frequently unrecognized either because of a failure to seek medical attention or a failure to obtain proper radiographs. The scapular AP is useful to evaluate the position of the humeral head in relation to the glenoid, particularly when anterior dislocation is present (Fig. 8-4). The radiographs should be scrutinized for evidence of associated fractures of the proximal humerus or glenoid, as multiple authors have documented the presence of associated fractures of the shoulder in up to 50% of patients with glenohumeral dislocations.8,11,17 The scapular lateral (Fig. 8-5) may be useful for the identification of posterolateral impression defects, and the direction of glenohumeral dislocation; however, the presence of multiple overlapping structures, such as the posterior thorax and scapular body, frequently obscures osseous details and thus limits its clinical utility. FIGURE 8-4 Scapular anteroposterior (AP) radiographs of a chronic anterior dislocation (A) and posterior dislocation (B). Note the anteriorly dislocated humerus is externally rotated and the posteriorly dislocated humerus is internally rotated. The axillary projection is invaluable in determining the direction of glenohumeral dislocation, size, and location of impression fractures of the humeral head, degree of glenoid bone loss, and identification of associated fractures of the glenoid, coracoid, or acromion (Fig. 8-6). A standard axillary radiograph is obtained with the patient supine and the shoulder abducted at least 40° with the beam centered in the axilla. A Velpeau axillary view may be obtained in patients who are unable to position the shoulder for a standard axillary view due to pain or limitation of motion. It is obtained by having the patient lean backward 30° over the x-ray table with the shoulder in adduction and internal rotation (sling position). The beam is then centered on the glenohumeral joint from a cephalad to caudad direction, with the film cassette placed on the x-ray table behind the patient. Although helpful, the Velpeau axillary does not provide as much information as the standard axillary projection. Of the three orthogonal projections of the shoulder trauma series, the axillary radiograph is most valuable for guiding treatment that is based on the percentage of articular involvement of the humeral head defect. FIGURE 8-5 Scapular lateral radiograph of a chronic anterior dislocation (A) and posterior dislocation (B). In both views the glenoid is clearly visualized because of the displacement of the humeral head. FIGURE 8-6 (A) Axillary radiograph of a chronic anterior dislocation showing the humeral head locked on the anterior glenoid rim. (B) The posterior dislocation shows the humeral head locked on the posterior glenoid rim. Computed axial tomography (CT) images are useful in treatment planning to further characterize humeral head impression fractures and to evaluate glenoid bone loss. As the treatment of humeral head impression fractures is based largely on defect size (and chronicity of the injury), it is often helpful to obtain CT images to quantify the degree of head involvement. Some authors recommend performing a CT scan only if the humeral defect is greater than 20% of the articular surface to more precisely define and characterize the defect, and to determine if associated glenoid injury is present.18,19 We prefer to obtain a CT scan for all patients with chronic glenohumeral dislocations because of the additional information it provides. Two-dimensional sagittal and coronal oblique reconstructions may aid in fracture characterization but are not essential. Although magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be useful for evaluation of concomitant injuries to the rotator cuff, this is not a common finding in patients with chronic dislocation. As such, MRI is not generally obtained; however, if a patient presents with a constellation of symptoms and signs not completely explained by the osseous injury, MRI may be helpful.3,20 In such cases, estimation of the humeral head defects may be performed on the axial MRI, thus obviating the need for an additional CT scan. Electromyography and nerve conduction studies should be obtained in cases of suspected nerve injury. An association between traumatic shoulder injuries and nerve injuries has previously been established, with up to 45% of patients with anterior shoulder dislocation sustaining nerve injuries, most commonly to the axillary nerve.1,11,12 These studies should be performed preoperatively to document that the deficit is injury related. Arteriography should be performed in cases of suspected vascular compromise, as axillary artery injuries in association with shoulder dislocations and proximal humerus fractures have been well documented.13–15 As the management of humeral impression fractures remains a challenge to the treating surgeon, it is essential that the physician maintain a thorough understanding of the available treatment options in the context of an organized, disciplined treatment algorithm. Satisfactory pain relief and optimization of functional recovery are the main goals of treatment; it is therefore incumbent upon the treating physician to establish with the patient and family reasonable expectations for each treatment approach. The desire to perform aggressive, often technically demanding interventions should be tempered by the patient’s general health and functional requirements, as well as the anticipated degree of recovery and the patient’s ability to participate in a postoperative rehabilitation program. The management of impression fractures of the proximal humerus necessitates consideration of many factors. Patient factors, such as age and medical comorbidities, affect whether the patient should be considered a surgical candidate. Injury-related factors, such as defect size, displacement, and chronicity, influence the selection of operative procedure. The availability of specialized equipment and implants, and the expertise of the surgeon may determine whether appropriate referral should be made to centers familiar with treating these often complex and challenging fractures. Nonoperative treatment of humeral head impression fractures in association with chronic dislocation may be undertaken in patients with minimal pain and functional disability (Fig. 8-7). Elderly patients with low functional demands may demonstrate excellent adaptation following resolution of the acute shoulder injury. These patients may have small or large anteromedial or posterolateral surface defects and may have adapted sufficiently to perform basic ADL, usually in conjunction with a functional contralateral upper extremity.21,22 Nonoperative treatment of impression fractures may also be desirable in patients with an unacceptably high medical risk, patients with uncontrollable seizures, or patients physically or mentally unable to comply with postoperative instructions or rehabilitation. In these cases, supportive measures should be instituted, including a brief period of sling immobilization, nonnarcotic analgesia, and gradual mobilization of the shoulder with physical therapy based on the degree of deficit present. FIGURE 8-7 (A,B) A 69-year-old man with bilateral chronic posterior glenohumeral dislocations. (C,D) CT scans show reactive bone formation about the posterior glenoid consistent with chronic dislocations. (E-G) The patient had limitation of range of motion, but he was reasonably comfortable and functional for activities of daily living; therefore, nonoperative management was the preferred treatment. (Adapted from Zuckerman JD. Comprehensive Care of Orthopaedic Injuries in the Elderly. Baltimore: Urban &Schwarzenberg, 1990:287–288, with permission.) Patients with chronic dislocations in whom nonoperative management is preferred should be started on pendulum exercises as well as a progression of active-assisted and active range-of-motion exercises. Exercises should be performed gently with the goal of regaining functional range of motion for ADLs at waist level. Forceful stretching should be avoided to minimize the risk of additional injury. Strengthening exercises are generally limited to isometrics and gentle resistive strengthening. In these patients, we are trying to achieve a “limited goals” outcome. Several authors have reported their results of nonoperative treatment of humeral impression fractures associated with chronic dislocations. In 1952 McLaughlin16 reported a series of 16 patients with chronic posterior dislocations of the shoulder associated with anteromedial impression fractures. Three were managed nonoperatively and all experienced unfavorable outcomes, with severe restriction of shoulder motion, an inability to raise the arm above the horizontal, disabling pain, and muscular atrophy.16 Hawkins and coworkers8 reported on seven patients with an average follow-up of 5.5 years who were treated nonoperatively for anteromedial humeral defects in association with chronic posterior shoulder dislocations. Only two were able to raise their hands above head level, although pain ratings and functional losses did not progress beyond immediate postinjury levels. Rowe and Zarins3 noted that of patients with humeral head defects associated with chronic shoulder dislocations, patients with anteromedial defects (posterior dislocations) had higher functional scores and functional range of motion than their counterparts with posterolateral defects (anterior dislocations). They attributed this difference to the position of the humeral head defect on the glenoid rim. They felt that the adducted and internally rotated position of the posteriorly dislocated shoulder was more functional than the abducted and externally rotated position of the anteriorly dislocated shoulder.3 The surgical management of humeral head impression fractures in association with chronic dislocations requires consideration of many factors that will determine the procedure to be performed (Table 8-1). Advanced patient age may steer the surgeon toward prosthetic replacement in the presence of a large defect, particularly if underlying degenerative changes are evident. Other patient factors that should be considered include hand dominance, functional capacity, vocational and avocational requirements, medical comorbidities, and ability to comply with postoperative instructions and rehabilitation. Injury-related factors that influence the surgical decision-making process include the size and location of the humeral impression defect; the bone quality and quantity of the humeral head; the presence of underlying degenerative changes of the glenohumeral articulation; and the chronicity of the injury, that is, the length of time since dislocation.

Humeral Head Impression Fractures and Head-Splitting Fractures

Humeral Head Impression Fractures

Humeral Head Impression Fractures

Clinical Evaluation

History

Physical Examination

Radiographic Evaluation

Standard Radiographs

Special Imaging Studies

Ancillary Studies

Treatment

Nonoperative

Operative

Patient factors

|

Injury-related factors

|

Other factors

|

Of particular importance is the ability of the surgeon to treat humeral head impression fractures. The surgeon should be familiar and comfortable with the management of such injuries. Specialized equipment, such as special shoulder retractors and table positioners, may facilitate the procedure. Implants, such as proximal humeral prostheses in a variety of head and stem sizes, should be available. Finally, physical or occupational therapy should be available to facilitate postoperative recovery and maximize functional outcomes.

Anteromedial Impression Fractures

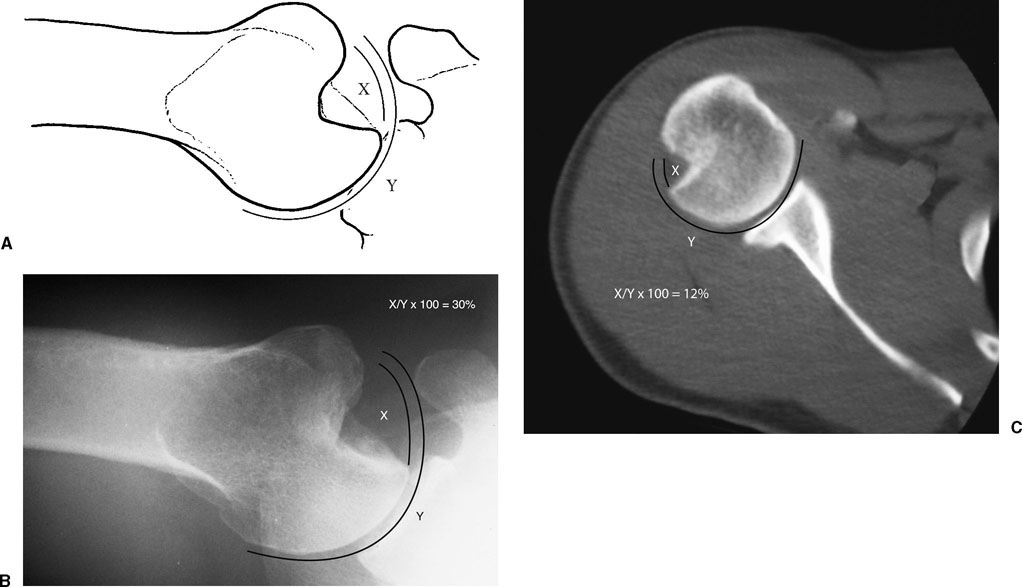

Most authors addressing the treatment of anteromedial impression fractures associated with chronic posterior shoulder dislocation have based their treatment approach on the size of the humeral impression defect.3,8,11,16,21–24 Calculation of the degree of articular involvement is based on the axillary radiograph or CT images. The percentage of articular involvement is determined by measuring the arc of the area of impaction divided by the total arc of the intact articular surface, multiplied by 100 (Fig. 8-8). Treatment recommendations based on this calculation reflect the propensity of the anterior glenoid rim to “fall into” the humeral head defect with the shoulder in adduction and internal rotation. In addition, the chronicity of the injury must be considered, as associated articular cartilage degeneration and osseous compromise are directly related to the duration of dislocation.

FIGURE 8-8 (A) The size of the impression fracture is an important factor to determine treatment. It should be described as the percent of articular involvement-based measurements of the arc of the area of impaction (X) divided by the total arc of the articular surface (Y). (B,C) Impression fractures can vary greatly in size.

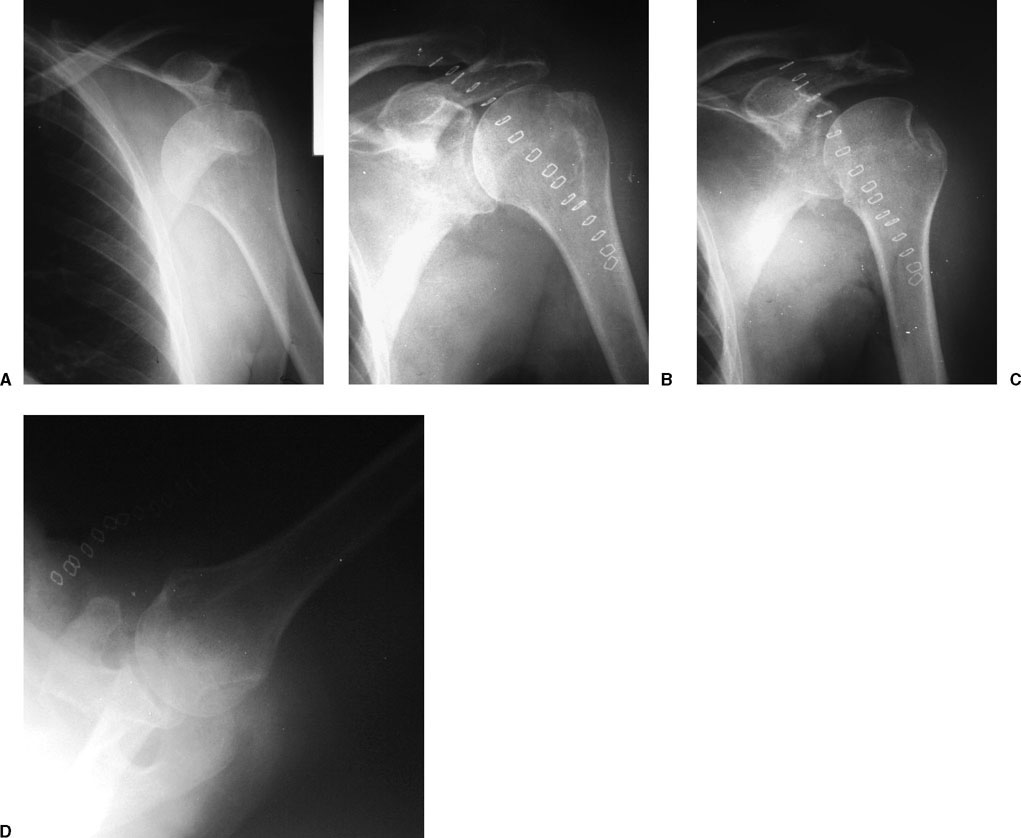

With anteromedial impression fractures involving up to 40% of the humeral articular surface, there are many options available to the treating surgeon. These include disimpaction and bone grafting, subscapularis tendon transfer, lesser tuberosity transfer, and allograft reconstruction. When the defect is greater than 40% of the articular surface, prosthetic replacement is indicated. Articular defects associated with a dislocation of less than 3 weeks’ duration may be amenable to disimpaction combined with bone grafting, as the impacted articular cartilage is usually viable. Defects associated with dislocations of between 3 weeks’ and 6 months’ duration can usually be treated by nonprosthetic reconstruction, because the remaining articular cartilage maintains viability. Dislocations present for more than 6 months are usually associated with articular cartilage degeneration and usually require prosthetic replacement; however, it is important to recognize that these are only guidelines, and each case has to be individualized. In certain situations, closed or even open reduction may be attempted for a chronic dislocation. If the shoulder is stable through a functional range of motion and the cartilage appears viable, no further intervention may be needed (Fig. 8-9).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree